Chapter 12 ~ Grass Roots Economy

A plane left Fort Chimo on the night of July 15, bound for Port Burwell, but Rosemary and I were not among the passengers. Instead, a posse of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police dressed in breeches and red coats went in it to give a symbolic display of law to a certain Eskimo named Noah.

Noah was causing trouble in Port Burwell, a camp of about thirty Eskimos, and he had accomplished it in the not unusual Eskimo practice of taking unto himself a second wife. His actions had roused passion among the other Eskimo men, because Noah was elderly – close to 60 years old – and the young men in the small settlement were jealous of him securing the affection of a young, marriageable woman. To compound the matter, Noah’s first wife, Emily, was still very much alive, although according to account, she took less exception to Noah’s amorous adventure than did the young men of Port Burwell. Hunting rifles had figured in the reports, so on the maxim that prevention of crime is better than its perpetration, the Mounties flew in to warn Noah and the young hunters of the consequences if their tempers flared too wildly.

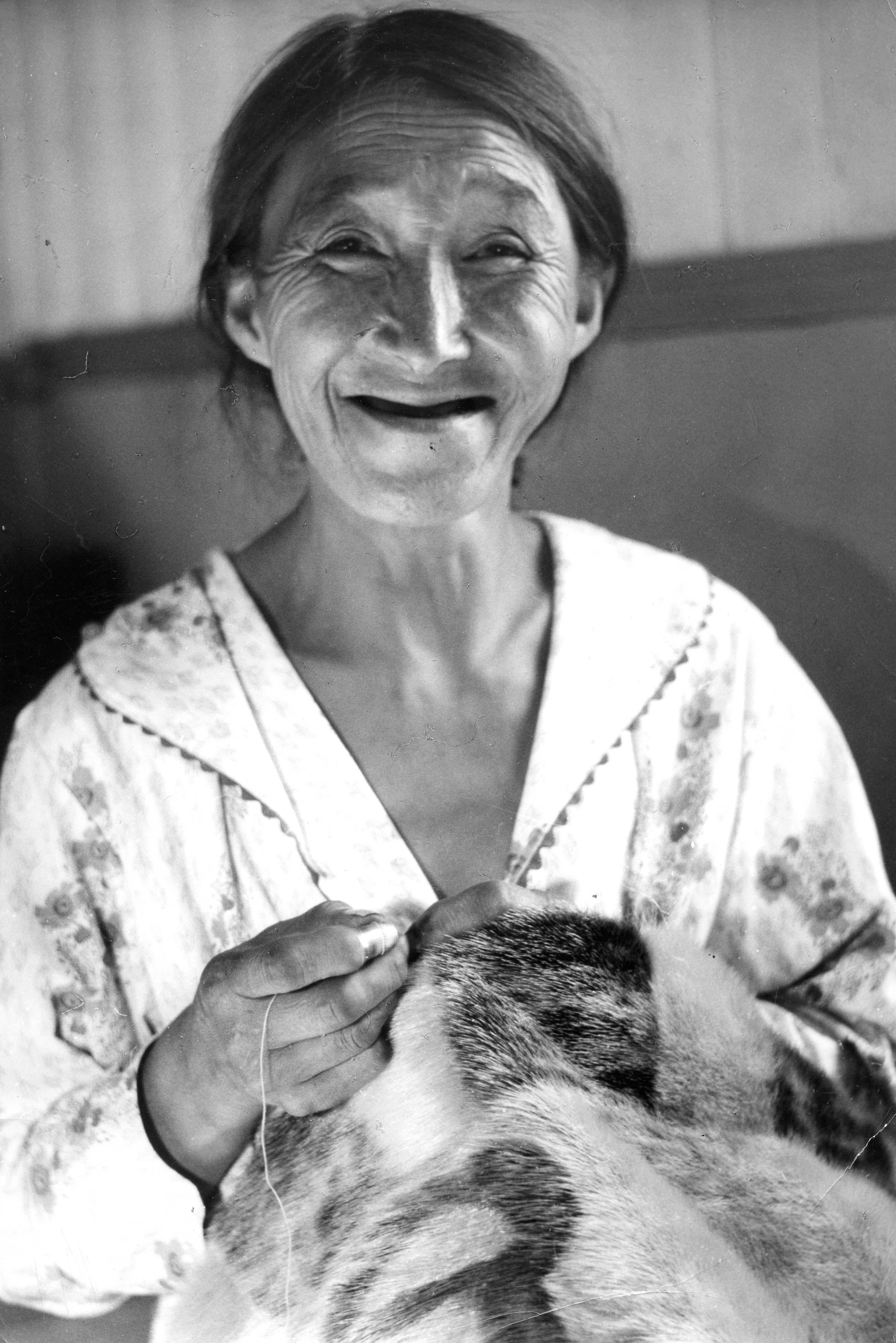

It was an unpropitious moment for the arrival of two journalists, so we remained in Fort Chimo and a handcraft development officer from Ottawa, Bill Larmour, went in our place on the aeroplane with the police and with a cargo of cured sealskins for the women sewers of Port Burwell, reputed to be the finest needlewomen in the Arctic.

The weather continued fine and on receipt of a favourable weather report on the radio from George River, we had a hurried breakfast of tea and oatcakes early on the morning of July 16, and packed our gear ready to go.

The Wheeler Airline traffic agent called for us in his four-wheel drive Land Rover, and accompanied by Mr. Dodds, the administrator, we sped off through the scrubby woodland road, southwards in the bright morning air. A broad clearing widened ahead, and instead of an airstrip, as I expected, we drove on to the sandy shore of a lake where a seaplane was moored.

It was the first inkling I had that our journey was to be by seaplane. Our destination, George River, lay in the type of country Arctic old timers referred to as The Boondocks, a region without a road, or an airstrip, close to the back of beyond.

At the lakeside, two short wooden booms formed the dock and they were being extended. Two great mechanical grabs were gnawing into the lake banks and loading trucks, which moved the fill no more than seventy five-yards to the water’s edge, and tipped their loads into the “pier.” A gang of lethargic labourers levelled off the fill with shovels.

Directing operations was a man in nautical cap, bright yellow gloves, knotted silk cravat tucked inside his black and white check shirt, khaki drill trousers, a leather belt buckled below the belly button and in high heeled cowboy boots. Despite every conspicuous item of his outlandish garb, the predominant thing about him was a pair of shaggy eyebrows, glowering and black. His stance was that of a bull at bay.

At twenty minutes past nine, he walked towards us, peeled off his yellow gloves, pushed his cap to the back of his head and said:

“All aboard.”

He was the pilot. Phil Lariviere, one of the best-known bush pilots in the Arctic.

Concern for the dock, where he moored his plane, kept him busy with the construction gang when he was not flying, “You can’t turn your back for a minute,” he said, “If you do, they all stop work.”

We climbed aboard with our baggage and the pilot carefully stowed it evenly in the tiny fuselage, already crammed with rescue and emergency equipment – life jackets, rucksacks, rifles, sleeping bags, ropes and a pair of paddles, a fishing rod and landing net. We looked ready for anything and with Phil Lariviere in charge, we probably were. I was lucky enough to be given the co-pilot’s seat, and I strapped myself down, ready for the take-off.

Lariviere took off his cap and revealed a thatch of snow white hair, so I settled back, confident that he must have been flying safely for years in terrain, where often enough one mistake, or inexperience, can cost a pilot and his passengers their lives.

He turned and winked broadly, turned on his switches, started the engine and we taxied across the lake for the take-off.

By half past nine, we were airborne and Lariviere pointed downwards. The score of white men employed on the dock site had all stopped work and were leaning on their shovels as they watched us climb into the sky and set course to the northeast and George River. Below, the Land Rover snaked down the road back to Fort Chimo with parcels of excess luggage left behind because of their weight. Lariviere left nothing to chance.

We soon left all traces of trees, and beneath us the rocks, scoured by ice, looked like beaten copper. For a while we travelled over the barren landscape in the company of a prospector’s seaplane. It was bright orange coloured for easy spotting in the desolate barrens where its occupants were seeking mineral deposits, richly stored in the north tilted Canadian Shield. As the planes drew apart and Lariviere turned in a more northerly direction, the planes rocked wings in salute and the prospectors soon disappeared into the vast, wide sky to the south.

We passed over bright green muskeg, thousands of lakes linked by north flowing streams and rivers, on one of them lay an unoccupied HBC trading post, testimony to the decline of the Ungava Bay economy. We passed Whale River, Mukalik and Tuktuk rivers. Tuktuk is Eskimo for caribou. The river had been named long ago when the great herds roamed the vast plain. Northwards the ice still lay thick in Ungava Bay. It was mid-July, yet the shipping season had barely started. We thumped and shuddered through air currents, like a stertorous elevator, and little more than one hour after take-off, we sighted a cluster of eight white tents on the edge of an ice-strewn shore.

It was George River char fishery. The canvas tents, an aluminum shed, two canoes and a Peterhead boat were the only signs of life for more than a hundred miles north or south along the coast. Lariviere put down in the bay, a little to the west of the broad estuary of George River, and we taxied across the waves to tie up at the Peterhead boat. I climbed quickly out of the plane and stood on one of the floats with the water slapping and swirling about my boots as we lurched in the swell. Leaning on a strut I felt green faced and closer to travel sickness than I had ever felt in my life.

Three Eskimos in a canoe came out to pick up the party, and ferry us ashore. A young Eskimo boy in a sealskin kayak skimmed over the waves like a dry leaf in the wind to look at us, and we looked at him, equally curious.

He dipped his paddles with effortless ease, barely touching the water as he sped along. He was browner skinned than any other Eskimo we had yet seen and he had an unusual haircut. The back of his head was cut very short and the front was grown long and hung in a forelock. It was the summer style of the George River Eskimos.

Rocky promontories, scoured clean of any vestige of plant life, guarded the crescent shaped beach. The rock was peculiarly stratified, and lay like enormous mounds of peppermint candy in pink and white stripes. In the centre of the beach, like the bright jewel of a diadem, lay a glistening chalk blue floeberg.

In such a wild free place I expected there to be an Arctic stillness on the shore. Instead, the air throbbed with the pulse of a diesel engine. It came from the hut housing a deep freeze plant, hub of the Eskimos’ char fishery, heart of a new industry intended to revitalise the impoverished economy of East Ungava Bay.

The wind began to blow and rain started falling in the half hour that Mr. Dodds, the administrator talked with the Northern Service Officer in charge of the fishery. Lariviere became restless and went out to his plane, standing by and ready to hold it off the shore if the wind increased. White caps crested the waves, Mr. Dodds said, “I’d better not linger,” and wished us luck.

An Eskimo started the motor of his canoe and the administrator paddled through the shallows to climb aboard. He waved goodbye and the canoe sped to the seaplane, already tossing too much on the water. There was a roar from the engine and Lariviere taxied the Norseman beyond the rocky headlands to a take-off point. Minutes later, the airborne plane buzzed the camp, then quickly disappeared beyond the low hills rolling to the south.

We were almost alone, in real Eskimo country at last. We prepared to pitch our tent, but the Northern Service Officer, Keith Crowe, said it was too small for long-term comfort and he offered us the use of a larger tent, where he kept office supplies and a radio transmitter. It already held a camp bed for visitors, so we accepted, inflated our air mattresses and unrolled our down filled sleeping bag. We were under canvas at last, even though it was not our own.

Keith Crowe invited us to his living tent for a meal. He and his wife and two children slept in one tent on the floor and lived in another. Alongside were the similar homes of a small group of Eskimo women who worked, cleaning fish at the freezer site. Their children were in a residential summer school upriver, and their menfolk were camped on the barren islets scattered at the bottom of Ungava Bay, where they set their nets and gathered the fish.

Everyone lived by tide and weather, and because the fishing season was short, they even worked the night tide. Keith Crowe was adjusted to the irregular hours and took life in his firm-footed stride. He was a patient man, born in the North of England, he had an Arts degree from the University of British Columbia and he spoke Eskimo with a slow, recognisably Yorkshire accent.

Sitting in his tent, warming our hands round our steaming mugs of tea, he told us something of the char fishing venture. The people of the region had lived mainly by hunting and fishing, and by trapping in winter for fox, marten, otter and mink. With the furs they trapped, they bought rifles, ammunition, flour and tea at the Hudson’s Bay Company trading post. They used to use sealskins for winter clothing, for their kayaks and oomiaks, dog traces and harpoon lines. It was a bare existence, but it supported them.

After World War II, the fur trade slumped and the HBC closed the George River trading post for some years. The Eskimos became too poor to buy ammunition to hunt with, and were unable to renew their boats. They went hunting on the land with bows and arrows, or they threw stones at birds and hares to kill them. Some collected used cartridge cases and strung them together with cords to make a bolas and when they could get within throwing distance, they would bring down a hare as it ran, if they were accurate enough.

They lived on the brink of starvation, for there is little fat on a bird or an Arctic hare, and they were appallingly neglected by an indifferent government. At some time in the 1950’s, the government had the plight of the Eskimos thrust upon them and the job of halting the downward spiral began. Economists, sociologists and biologists went into Ungava Bay and in due course a programme of self-help was recommended. The char fishery was part of the self-help.

Marine biologists first studied the Arctic char and a fixed a limit of thirty thousand pounds weight which could be taken in one fishing season. An advertising campaign was conducted across southern Canada and a market was assured in luxury hotels, on railway systems, airlines and the best restaurants. Embassies and socialites were supplied with samples of Arctic char to launch the fish in society, and it was served at state banquets, yet the whole George River industry was hinged on a fallible diesel engine refrigerator and it had no engineer to maintain it.

A loan of twenty five thousand dollars was made to the George River people, to pay for the boats and tackle, the fuel oil and the freezer, and Keith Crowe of Ilkley in Yorkshire taught the Eskimos how to fish with the new style char nets. He taught them how to gut and fastidiously clean the fish for a luxury market and how to flash freeze them without bruising the flesh.

Later that same day, when a load of fish was brought in on the tide, I helped the Eskimo women to clean the bellies and wipe the slime from the chars’ skin. We stood at trestle tables in the open air, surrounded by persistent biting mosquitoes. The women wore parkas, Mother Hubbard dresses and gum boots. They sprayed each other generously with fly repellant, and through hours of drizzle and cold dampness, they stayed patiently at work, washing, rinsing, wiping tirelessly. It was tedious labour. “We could do with a power hose for washing, but we don’t have one, so it’s all done by hand,” said Mr. Crowe as he gave a final inspection to a full rack of char. He hung each fish by the throat on angled nails driven into a driftwood pole and when the rack was full, he and Eskimo Johnnie, heavily dressed, staggered under the weight and carried it into the flash freezer. As the door of the giant fridge was opened, a cloud of vapour poured into their faces and they disappeared inside to the 40 Below Zero Fahrenheit atmosphere to glaze the fish.

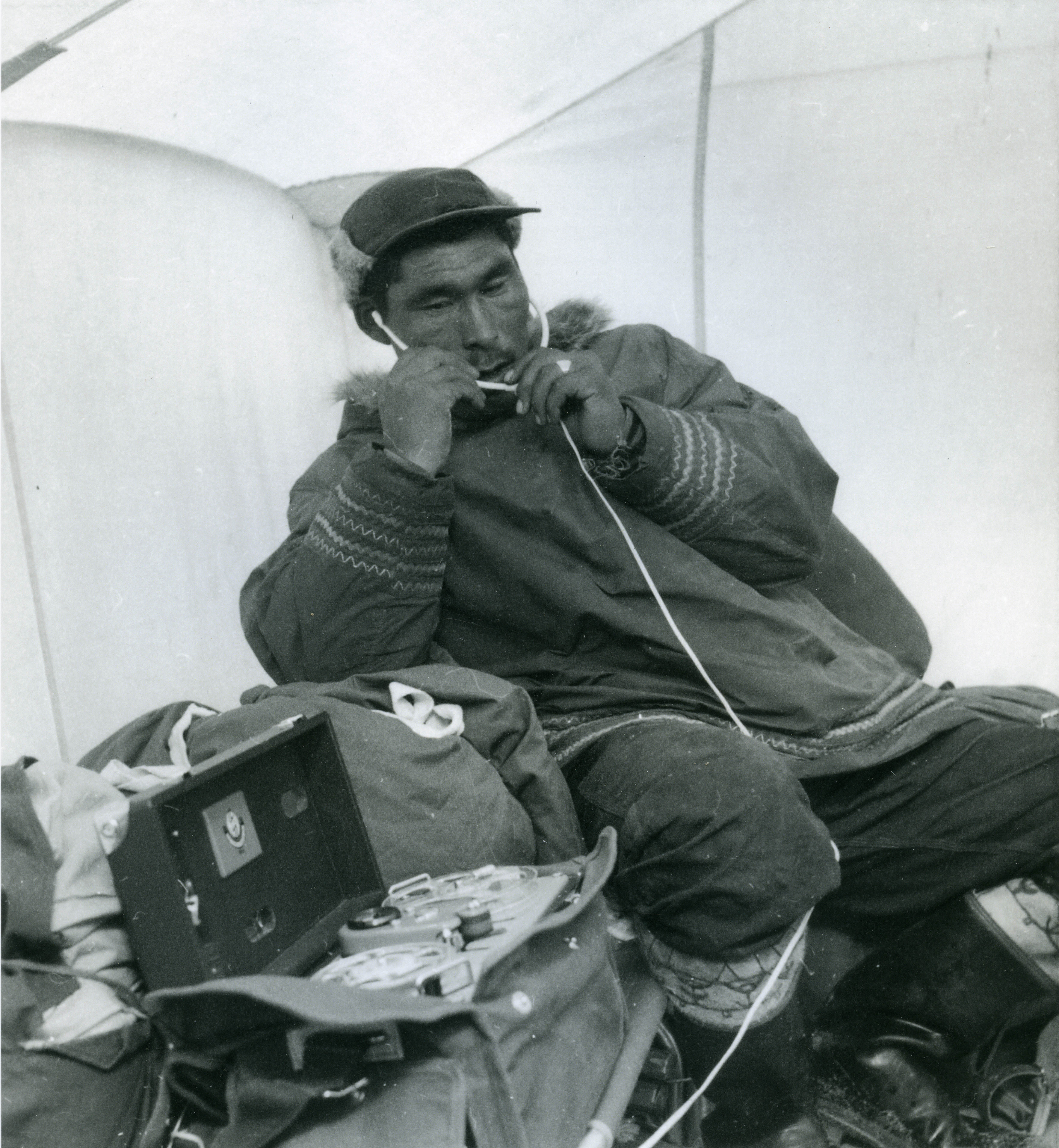

As we stood on the shore, a lone canoe put into the beach and a stranger came towards me. He introduced himself as Tom Ananak. When I left Fort Chimo earlier in the day I had been given a reel of tape on which was a message from a woman patient in Hamilton Sanatorium. The woman’s husband, was somewhere on the fishing grounds of Ungava Bay. As good luck would have it, the tape was made at seven and a half inches a second, which was the only speed at which my tape recorder would operate, and the tape had been given to me to carry in the hope that at some time I would cross the path of Tom Ananak.

I had been in the settlement less than six hours when Tom came ashore, summoned by the Tundra Telegraph from one of the remote islands. Somehow word had reached him that I had a message from his wife. He was a dark faced, frowning fellow with close-set eyes, immense shoulders and the most aggressive looking Eskimo I ever saw. When he discovered I could speak no Eskimo, he looked puzzled, so I beckoned him to follow me and led him to the office tent where my tape recorder was lying.

Tom sat on the edge of the camp bed and I put the reel of tape on the machine, plugged in the stethophone (a gadget like a doctor’s stethoscope) and the only means of listening in to my recorder. I handed the earpieces to Tom and he gazed back at me blankly. He knew nothing of such instruments, so I plugged them into his ears and switched on.

As the reel turned on the spindle his perplexity softened and suddenly, as he recognised his wife’s voice, he smiled enraptured. I played it to him three times and then he stood up to go and struggled for some English.

“Thank you. Nakomik,” he said, his face beaming, and he shook hands so vigorously I thought my fingers would never flex again. I stood at the door of the tent and watched him leave for the shore. His canoe was in the centre of the crescent beach. He stepped in and crouched at the stern, then without a backward glance he sped for the horizon. I watched until he was out of sight, the canoe’s path, a fleeting furrow on the water, straight as an arrow from a bow.

The tape he had listened to was the first news he had received from his wife for more than a year. She had been taken away with tuberculosis to the Outside, leaving him with no one to sew his sealskin boots or make his clothing, or cook his food or care for his children when he went hunting. His difficulties had been further compounded by a complete lack of news for the past year. A similar lack of communication existed among many families which were broken up through ill health and caused untold misery between men and women, parents and children.

Only the youngest babies and toddlers were kept at the freezer site, the other children were at the school-under-canvas, and by living close to the Eskimo women, we learned how remarkably gentle they are with their children. One of their most outstanding virtues was the quietness of their voices, and the gentleness they showed them.

Mr. Crowe said he once smacked his elder daughter for deliberately hurting her sister. Some Eskimo men, visiting his tent, opened their eyes wide with astonishment and gazed at him as though he were a brute, frowning and muttering among themselves. It was so unlike anything they would do or had seen done before. He said he was completely embarrassed by his visitors’ silent condemnation of his action.

There were always visitors in Mr. Crowe’s tent. The people gravitated towards him like children to a father. He bandaged their cuts, doctored their ills and diagnosed their complaints. He said he had never heard of an Eskimo with ulcers, they didn’t look to the future so they didn’t worry. ”If they worried, they wouldn’t live at George River because there’s plenty to worry about here,” he said.

When Mr. Crowe first arrived by dog team among the char fishermen, he almost immediately earned a reputation as a medical man. An epidemic was sweeping George River when he arrived with a supply of anti-biotics. There was no one else to administer the drugs, so he toured the settlement every four hours, jabbing Eskimos with a hypodermic needle, and except for a pregnant woman, everyone survived and his reputation was made.

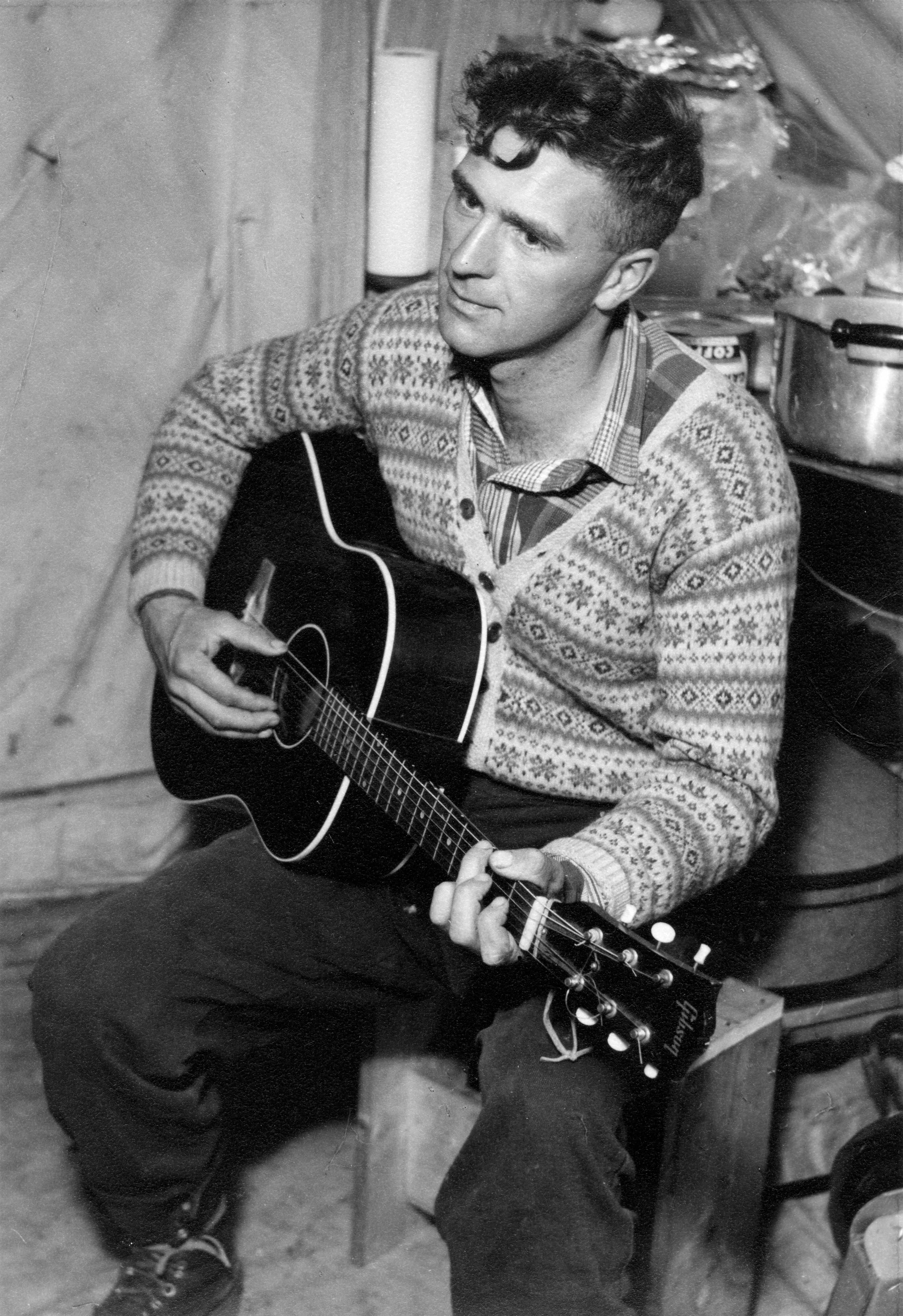

In such a remote place, kindness and beauty were of threefold importance and one of the greatest joys in that brave, small camp was the sound of Keith Crowe playing his guitar and singing in a rich baritone voice when the day’s labour was done. Seldom did such a lovely voice fall upon a more appreciative ear.

Perhaps it was the loneliness of that barren shore, the high hopes of the people and courage of the people and the courage of the venture which tinged his song, but as I went to bed on that first evening I heard his voice, haunting and melancholy. I stepped outside to listen. A moon hung low over the black tundra, and the Eskimo tents glowed from within with the soft light of oil lamps, pale as the moon in the velvet sky.

I was drawn to the sound like all the people who came from their tents and I went in to where he was sitting. The song unfolded lazily, bright smiles lit the Eskimo faces clustered at the tent door, and Keith Crowe, three thousand miles from home sang an old folk song about a spinning wheel, and though the lamps were dim I went outside, for I wished to hide my eyes.