Chapter 16 ~ Some Sex Customs

Out on deck next morning, I could see the boat was anchored near familiar coastline. We were opposite George River, and soon after breakfast, Keith Crowe came out to meet us and said the fishing was going well. He had been up all-night packing char, ready for export on a cargo ship.

Max wanted to sail up the George River to a community hall round which the summer boarding school, for the fishermen’s children was encamped, so as the tide filled the channel, we set off inland after putting the passengers and dog teams ashore to await our return. Two hours later we anchored opposite a beach and went ashore by canoe. As we rounded a headland, a log cabin, festooned with radio aerials and flanked by half a dozen tents, loomed on the cliff to our left. The cabin looked very trapper-ish, and more appropriate to Indian country than to the sub-Arctic tundra. A year previously, its logs had been felled up river and a gang of ten men, led by Max, had floated them downstream as a raft with the men herding stray logs. Not a limb was allowed to go to waste in a land so bereft of building materials.

We were greeted by the schoolteachers, Joan Ryan and Anne Will, who invited us so warmly to lunch we could not have refused. We ate together with the children in the log hall, on char, bannock and beans. Snow shoes hung in the corner, white and silver fox skins were stuffed out of harm’s way in the roof beams and there were bales of sealskins and boxes of embroidery thread, duffle cloth and braid for use by the women sewers at the fish camps.

The Eskimo children sat in White man’s fashion to dine at long tables. Their seats were planks salvaged from packing cases laid on sections of tree trunks and the school teachers’ chairs were upturned wood cartons.

It was the first school the George River children had known and was run entirely alone by the two young women who were foster parents and teachers during the fishing season. Eight weeks’ school was all the Eskimo children had in a year.

The reason for our detour up George River was to obtain some radio equipment for Port Burwell from the community hall. Dismantling the aerials took longer than Max expected, so we missed the tide and had to wait until nightfall before going down river.

By four o’clock in the morning we were back in Ungava Bay and Max was out on deck blowing his cow like foghorn – a groaning, hand-pumped affair to summon the Eskimos, who, he hoped, would be “arriving imminently,” but they failed to materialise and it was long past breakfast time when we formed convoy again and headed North, loaded with a full complement of huskies, jovial, well-slept Eskimos, and babies.

The day was misty and our boat rolled noticeably, which caused the first casualties, Paul Dubois, the engineer, retired abruptly from the lunchtime stewpot and submitted to seasickness. Max snatched a nap alongside the turning propeller shaft and Rosemary snoozed in the fo’c’sle. I set up business, sitting on the hatch cover, with my typewriter on my knees and wrote up my notes with a romantic fervour stating: “It is sheer heaven to be pitching through Hudson Straits in a forty-foot longliner. To have gone through in flat calm and blue sky would have had small sense of adventure.” And I tried to picture poor Henry Hudson and his crew as they tacked and hauled their way at the wind’s mercy through the uncharted waters and turbulent currents that converge at Hudson Straits.

Fantastic ice floes surged by us, duck-shaped, dog-shaped and one even like a horse drawn carriage with waves breaking through its windows. The longliner had to battle a powerful tide as we neared Port Burwell, but by eleven o’clock that night we entered a T-shaped canyon of high craggy rock. Max gave a blast on his foghorn; a light appeared on shore; the anchor splashed down and Bill Larmour’s welcoming voice called across the water – “The coffee pot’s on.”

It was like going home.

We scrambled up the cliff, lighting our way with hand lamps, up into the tiny settlement, built on a narrow, grass covered ledge. There were three small buildings and barely room for half a dozen tent rings where our fellow travelers pitched their tents and tied their dogs. The buildings comprised the freezer shed, the government officer’s hut and Noah’s packing case one-room home.

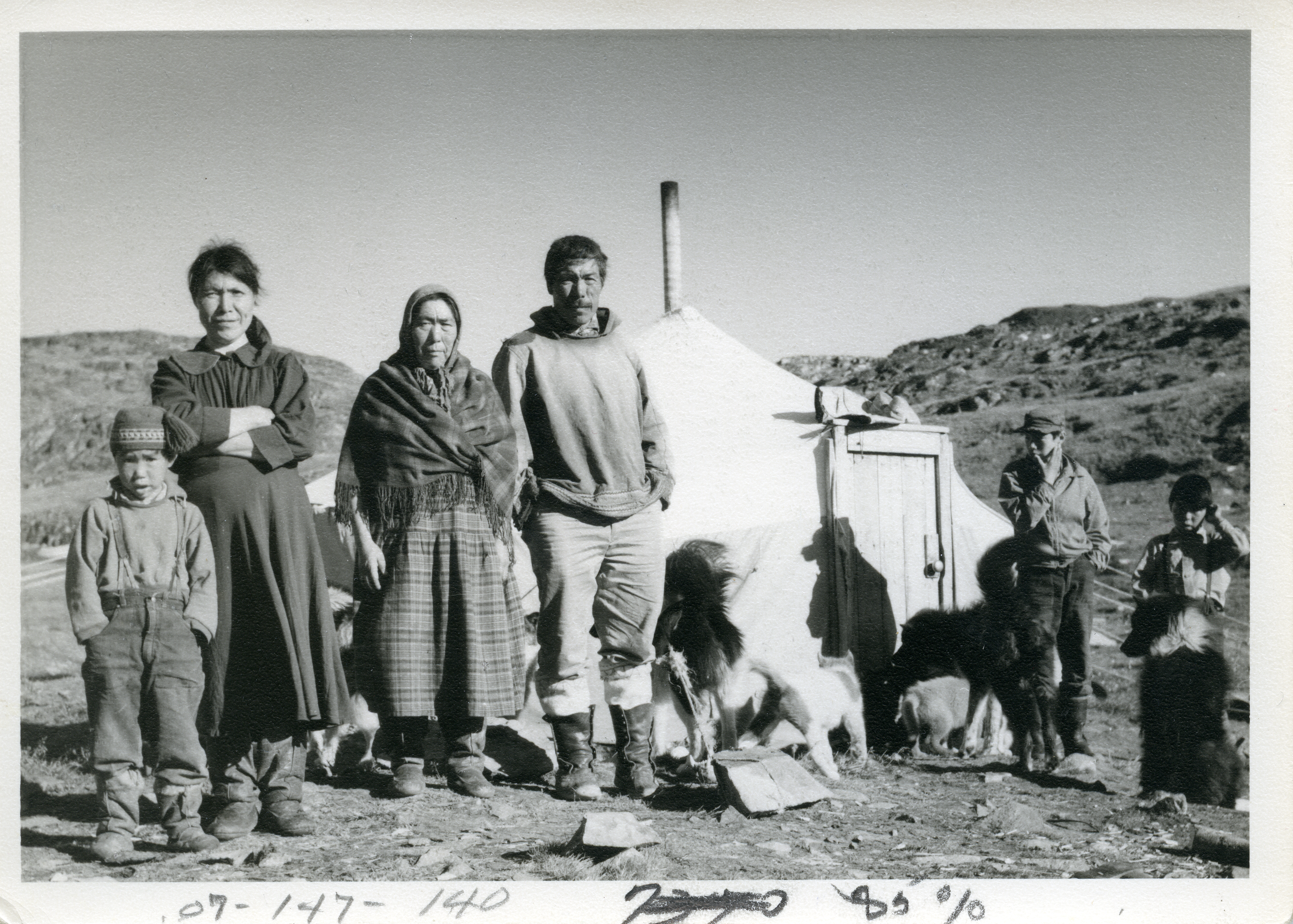

Half a dozen tents of the Port Burwell Eskimos were clustered in a cove on the opposite end of the bar of the T. There were less than thirty of them altogether, and most of them were elderly, the survivors of a flu epidemic which had decimated Port Burwell, once bustling and known as The Gateway to the Arctic.

We had barely sat down to drink our coffee in the government shed when Bill Larmour announced that Willie, one of the Eskimo hunters, had married in true Eskimo fashion earlier in the day. Bill was a conventionalist where the proprieties were concerned, and said: “When it was all over, I asked them, if they wanted to get married. I asked would Mr. Clarke the minister at Fort Chimo do. They said he would, so Willie can go down to Chimo on the longliner as pilot. That’ll save manpower here.” Max had other ideas, and he asked how it happened.

“Willie killed twelve seals today and was only half way through skinning them, He needed a wife. I suppose he got tired of skinning and decided it was time to get married,” said Bill.

In an Eskimo hunting economy, duties are clearly divided between the sexes, and when a hunter has killed a seal and dragged it back to camp, he takes little further interest in it, except to eat the meat, or unless he makes dog lines with the skin.

It is a woman’s job to skin the seal, flense and render the blubber, and cook the meat. Willie was about thirty years old and long past the age when most Eskimos marry. Catching twelve seals in one day had sickened him of his enforced women’s work. Trial marriage is still an Eskimo custom, so he resolved both of his problems by ending his bachelorhood and then promptly putting his new wife to work, skinning his six other seals.

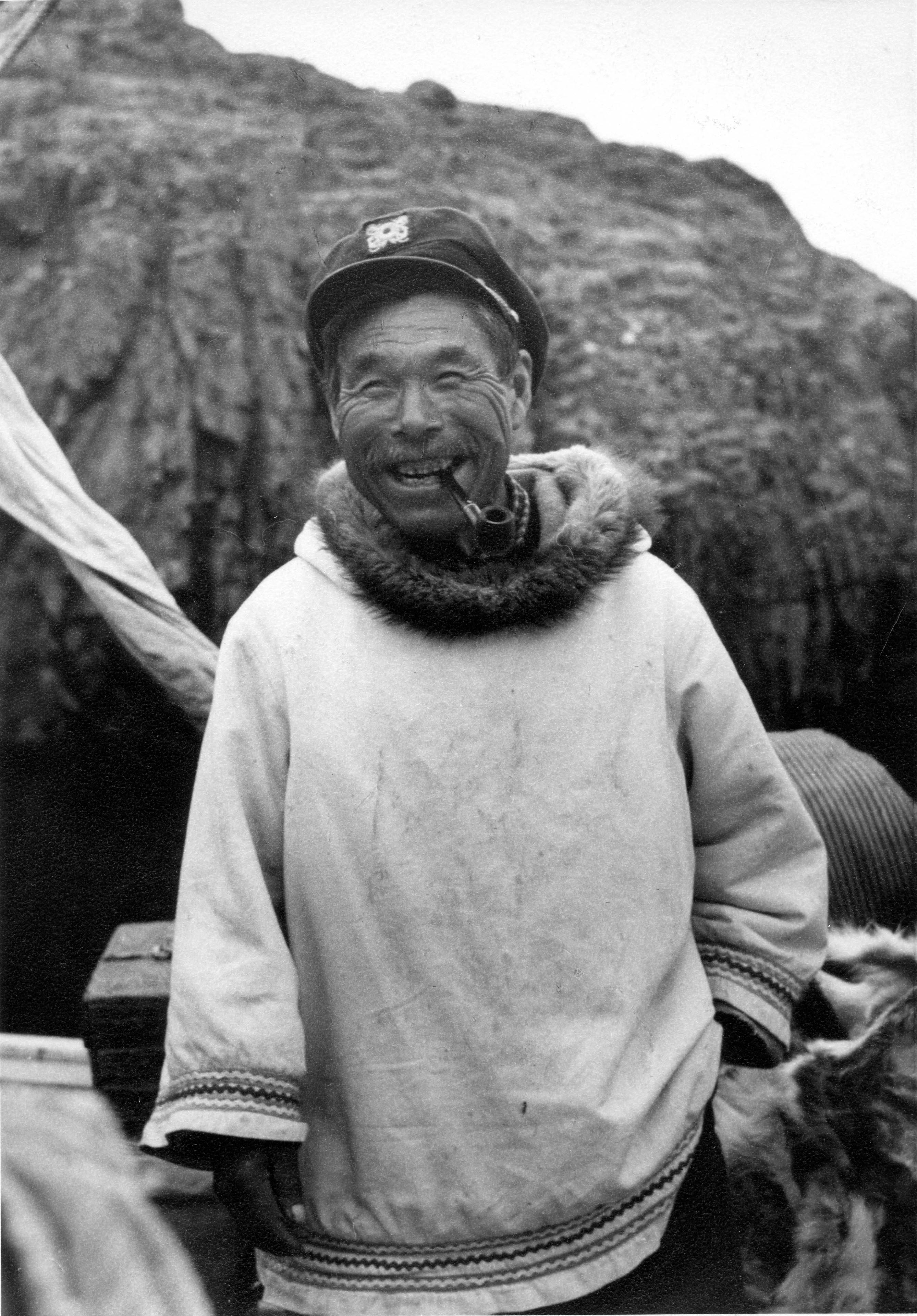

His fortune in catching so many in one day was due to the migratory instinct of the harp seals which pass Port Burwell, northwards, in July and again southwards, in November, when they go down to the Gulf of St. Lawrence for the pupping and breeding and molting in spring. Two days after Willie had made his lucky strike, the harp seals had left, bound for Davis Strait, Greenland’s coast and the North. Max sat puffing his pipe for a while, after Bill’s explanation, then he said: “You’d better raise Fort Chimo on the radio tomorrow morning. Tell them to have Mr. Clarke on the quayside with the book in his hand. I want this boat for the fishing. The season isn’t all that long and I want Willie out of Chimo on the same tide.”

The shortage of manpower for the fishing was acute. Also, the longliner was the only really dependable, seaworthy boat to bring the char from the fishing grounds, through the dangerous Straits of McLelan to the Port Burwell freezer.

After further consideration. Max decided he could spare neither the boat nor Willie, even to sanctify his marriage.

“Why do you have to marry them?” I asked.

“Well, they’re living together,” said Bill.

“Why doesn’t Max marry them on board ship. He’s captain, isn’t he?” I asked.

“A splendid idea,” said Max. “Give me the book and I’ll do it.”

Bill dampened the notion and said he had already promised Willie and his wife to go to Chimo. “I think they like the idea, and they think it would be very nice for Mr. Clarke.”

(Eskimos are probably the most obliging people in the world”.)

Max came from Labrador, a fishing country, “where,” he said, “you got wed at the end of the fishing season. Not at the start. Not at the middle, but at the end. Fishing comes first.”

He offered to quell Bill’s qualms by performing the ceremony in the wheelhouse of the ship. We could not find a prayer book. Max said any book would be suitable. The National Geographic Magazine was good and colourful, and if that was not good enough, he had an excellent diesel engineer’s handbook.

“I can marry them well enough. Once on Labrador, I successfully divorced a Roman Catholic couple. They were Indians and they stayed divorced for five years. They used to fight each other so much I thought there might have been a death in the family. Divorce seemed the best thing and they were both in favour of it,” he said.

Years afterwards, the priest who had married the couple returned to the camp and discovered they had married again. He asked what they were doing living in sin, and they explained to him they had been divorced by Mr. Budgell, “I wish I’d seen his face,” said Max. The trouble with Max was you could never tell when he was pulling your leg. And I think Bill Larmour could not tell either. So the matter of Willie’s wedding remained unresolved and it was put aside, at least until the end of the season.

The fishing grounds which were to supply the Burwell freezer with char lay several miles down the Atlantic coast of Labrador. The journey had to be made through McLelan Strait, separating the mainland from the Island of Killinek on which Port Burwell was situated. Killinek was Eskimo for “The End of the Land” and the narrow channel which formed its southern boundary was a vicious stretch of water that was not recommended for large vessels owing to the strong tidal stream in its narrows, and not very good for small vessels either.

Nor was it deemed advisable to attempt the strait without a pilot. The man who was to lead us through the straits to the fjord of Ikkudliayuk was Henry Anatok, a cheerful, handsome man of about sixty years, and brother to the doughty Noah. Both men had lived through the epidemic of 1918-1919 when the Moravian Mission ship, the square-rigged Harmony, carried Spanish flu to the isolated camps on Labrador.

In those days, the Moravians operated trading posts at the mission stations, where trappers could exchange furs for supplies, or test the missionaries’ brotherly love by obtaining credit in lean times. It was said all along the coast that the Moravians never turned away anyone who was in need. By the end of the war in 1918, the stores were sorely in need of supplies, and the good ship Harmony was eagerly greeted when she reached the coast, her holds full of goods. At each harbour, Indians or Eskimos, half breeds and settlers helped to unload the supplies and carried them into the trading posts. But as the old Harmony travelled North, the Spanish flu spread in her wake in an epidemic which killed hundreds of people.

The welcomed goods stood on the shelves, untouched, there were so few people to purchase them. The coast never recovered from the tragedy. At Port Burwell, the population fell from two hundred to less than thirty souls. In Okak, seventeen out of a population of four hundred lived to mourn their dead and the camp became a ghost place. The survivors could not bury the bodies fast enough, and so they were committed to the harbour, wrapped about with rope and weighted with stones.

In 1926, some of the ropes began to break apart and the bodies rose to the surface, their features still clearly recognisable, perfectly preserved by the icy cold water which would not support parasites and people no longer stayed overnight at Okak. The fjord of Ikkudliayuk, where the fishery was to be established, had a similar history.

Port Burwell’s decline was rapid after the epidemic. The Moravian trading post was taken over by the Hudson’s Bay Company, but they too eventually had to close it down. Thereafter, the Eskimos’ nearest trading post was a hundred and fifty miles away up the George River – a journey which they made once in winter, and perhaps once again in summer. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police withdrew, there were not enough people to warrant any showing of the flag. The Moravian Mission finally left in 1928 and the buildings gradually- disintegrated until only a few red bricks of the foundations were discernible in the long green grass where the Eskimos pitched their tents.

For a while, the government tried to winkle the Port Burwell people from their rocky outpost, but the people ignored the blandishments and preferred independence at Killinek, the End of the Land, to the moral rot, living on relief and lolling about the HBC trading posts up George River or at Fort Chimo.

There was no doubting the courage of the Burwell Eskimos. They had really good hunting for no more than five weeks a year when the herds of harp seals passed by; but there were polar bears, ducks, hare and ptarmigan, cod and char, if they went fishing. But fishermen need boats, and they had been poor for years, so their expeditions were limited by the seaworthiness of their old craft in summer and by the stamina of their dog teams in winter.

Noah told me the weather was so violent in October and November, when the seals passed south, that the people often had to move about the rocks on their hands and knees, and he made sure I understood him by getting on all fours to show me exactly what he meant. Seal hunting was sometimes a failure, and then winter was a hungry thing to be endured. The harbour of Port Burwell was sometimes calm inside when a gale was blowing out in the Straits, and we waited for several days until our pilot, Henry Anatok, decided the weather was suitable. The party busied themselves about camp while the gale blew itself out. Bill Larmour showed the women sewers the type of sealskin hat he wanted made from the cured sealskins he had taken in with him, and he made an inventory of the articles already made by Noah’s wife, Emily. Paul Dubois worked hard on his refrigerator engines and appeared only briefly for meals before vanishing once more into the freezer shed. Rosemary worked away at her photography and I wrote a few stories for my newspaper and we both kept house for the party.

Max rigged up the aerials he had filched from the George River community hall, then he built a water supply line down the hill to the freezer site so the fish could be cleaned the more easily. Plumbing was no new trade to Max.

He told us that after he took his English bride back to Labrador, he decided it was about time someone introduced indoor plumbing to Nain. Every man is a handy man in Labrador, so he wrote to the advertisers in a mail order catalogue and ordered a complete domestic plumbing outfit. Boiler, tank, piping, lavatory, bathtub and basin.

When it arrived months later by cargo ship, willing hands helped him to haul it up the shore. Everyone wanted to see the new plumbery. An old sea captain helped him to install it, and when the job was finished, old Captain Carter was dirty and said he would initiate the system by having a bath.

He turned on the hot water taps, but only cold water gushed out. It proved the water was running though. They smoked a pipe or two of tobacco, waiting until they thought the water had had a better chance to circulate. There was no doubt it was hot, the water was boiling and bubbling in the pipes.

Again, Captain Carter tried the bathtub, but again he was unlucky.

“If I can’t wash in it, at least I can try the lavatory,” he said, or words to that effect, and he disappeared into the smallest room in the house. He flushed the cistern and out came a boiling hot cloud of steam, said Max, “We were just amateurs you see, and we’d connected her up wrong. But that’s the origin of the expression, A Fine Head of Steam.”

Rosemary and I also assumed another office, gathering graveyard puffballs. The puffballs were discovered by Bill Larmour who swore they were edible and proved it by having them fried with his tinned bacon for breakfast each morning, and then eating them.

The puffballs grew high up the hillside in a graveyard made by the Moravian Missionaries. I used to leave the others and walk there on my own sometimes, because though we were such a small group of people, we lived almost in each other’s pockets and there was tranquility on the hill, away from the communal hut.

Standing up there in solitude, I was pervaded by a tremendous sense of space and of wonderment at the Eskimos’ courage. Even the plants had to fight hard for survival. Away to the east rolled the Atlantic Ocean, studded with majestic icebergs. Westwards was the turbulent entrance to McLelan Strait and below me, the sea fingered its way into the harbour. At my feet pale yellow Arctic poppies grew and two snow buntings chirruped happily as they hopped from post to post on a paling fence surrounding the only two named graves in Burwell. They were for Ada Jessica Lyall and August Lyall, a brother and sister who died, within a short time of each other in 1920. Lyall was a name well known on the coast of Labrador and inevitably, Max Budgell had the story.

The young man, August Lyall had acted as guide for a Mountie going out on a journey late in the year when a fierce storm blew up, capsizing the boat. Both men reached shore and Lyall, who had fared the better of the two, elected to return overland through a blizzard to Burwell to get help for the policeman. He scraped a hole in the snow and built a wind shield for his companion who was suffering from exposure, and set off alone.

He almost reached Port Burwell when his strength ran out and he fell in the snow close to home. Next morning, his body was found frozen and the people followed his tracks, seeking the body of his companion. They found the policeman, frostbitten but alive, and August Lyall was buried on the hill and when the settlement was abandoned by the White men, the Lyall family went down the coast to Nain where some of them live to this day.

Nature seemed to take care of their graves, for certainly no-one was there to tend them. Inside the neat paling fence, the yellow Arctic poppies seemed to bloom larger than anywhere else on the hillside, and the two snow buntings hopped and sang like two bright spirits on the cool air.