13 Coming to the Plateau, 1972-1976

Changes in residence life. Flexibility in Arts and Science. Registrar’s office, 1952-73. Trouble in Classics, 1968-74. Accrediting the Library School, 1973. Graduate Studies, 1972 and after. A new Faculty of Administrative Studies, 1975. The Atlantic Institute of Education, inception and demise, 1970-82. Trying to expand Dentistry, 1966-82. The Medical Faculty, 1972-80. Expanding the Law School. The Dalplex saga, part 1, 1966-76.

Changes in residence life. Flexibility in Arts and Science. Registrar’s office, 1952-73. Trouble in Classics, 1968-74. Accrediting the Library School, 1973. Graduate Studies, 1972 and after. A new Faculty of Administrative Studies, 1975. The Atlantic Institute of Education, inception and demise, 1970-82. Trying to expand Dentistry, 1966-82. The Medical Faculty, 1972-80. Expanding the Law School. The Dalplex saga, part 1, 1966-76.

love –

as your mind

grows to the one

beside you

touch her hand

accept her gift

and sleep.

It all suggested that the days of the NATO girl, “No Action, Talk Only,” a Gazette complaint of 1964, was anachronistic by 1969. Under the new rules in Howe Hall women were allowed in all areas from 9 AM to 3 AM, seven days a week. In Shirreff Hall male guests were allowed in rooms from 12 noon to 3 AM on weekdays, and from 9 AM to 3 AM on weekends. After 6 PM male visitors had to be signed in by a resident who registered her name and room number; the 3 AM limit for male visitors to be out of rooms was enforced, a peremptory buzzer sounding its warning in the room. In January 1970 a Shirreff Hall referendum asked, “Are you satisfied with the present visiting hours?” Some 85 per cent of Shirreff Hall residents voted, and the result was overwhelming: 95 per cent of the young women voting preferred the new system.[1]

In April 1979 the rules were liberalized again. The board’s Residence Committee, chaired by Dr. J.M. Corston, recommended that except for freshettes, women at Shirreff Hall could have male guests in their rooms the whole weekend, from 6 PM Friday until 9 AM Monday. That proposal came from the Shirreff Hall residents themselves, though this time some 25 per cent opposed it, as did Christine Irvine herself. Nevertheless the board proceeded, providing designated areas for those who did not want the extension of hours, and also provision for male washrooms. Christine Irvine and Mrs. D.K. Murray, president of the Women’s Division of the Alumni, felt that Dalhousie “was degrading Shirreff Hall by allowing female students to accommodate male visitors in their rooms,” and setting a bad example for freshettes. Hicks told the board in September 1979 that this was now a fait accompli, but that there would be a review. That satisfied neither lady. Zilpha Linkletter, who chaired the board’s budget committee, also wanted her vote recorded as opposed. It was probably a contest difficult to win; 75 per cent support from the Shirreff Hall residents was not easy to combat. It was also a contest between new ways and old, and for better or worse, the new won.

There is some irony in the conclusions of the review that took place a year later. Christine Irvine reported that the use of the weekend visiting privilege had not been at all widespread, that on the average weekend there were as few as eleven visitors registered. The Women’s Division of the Alumni continued unhappy, but the board’s Residence Committee concluded that the new policy was presenting no problems, that there had been no complaints from resident girls, nor from the dons nor from parents.[2]

These residence rule changes of 1969 and 1979, and their acceptance, show how far the sexual revolution, and the pill, had changed mores in fifteen years. As late as 1964 such rules would have been unthinkable; by the 1970s they were clearly possible. Dalhousie accepted what had clearly come from the residents themselves.

Changes in Arts and Science

In 1972-3 there were 7,335 Dalhousie students, of whom 14 per cent were part-time. While the total rose only by 3 per cent in 1973-4, the big jump in the 1970s was the 12 per cent increase from 1973-4 to 1974-5, from 7,544 to 8,447. After that, registration levels evened out, rising slowly in the late 1970s, reaching 9,018 in 1980-1. By then part-time students were noticeably on the increase, some 17.5 per cent of registration. Part-timers in Arts and Science were 16 per cent, Health Professions 17 per cent, and Graduate Studies 24 per cent. There were none in Medicine. About 42 per cent of all students at Dalhousie were women, and the percentage would continue to rise through the 1970s. Part-time students were about 56 per cent women in 1975 and 60 per cent by 1980.[3]

There were also substantial changes in the Arts and Science curriculum, though not nearly as extensive as some students, and the Dalhousie Gazette, talked about. As of the autumn of 1969, experimental classes in any subject could be formed on the initiative of students or faculty, subject to announcement of it in the calendar if far enough in advance, or in the Gazette or in the new (1970) University News. A faculty member had to be rapporteur and submit a report on the content and work of the class to the Faculty Curriculum Committee.

As of 1 September 1969, English 100 was no longer a required subject for the BA, B.Sc. and B. Com. Professor S.E. Sprott warned faculty that levels of verbal skills in students were already declining and abolition of English 100 would be “another nail in the coffin.” Nevertheless it carried, by twenty-nine to five. With that went also the abolition of the compulsory language requirement. These changes were part of a general increase in the flexibility of the BA and B.Sc. programs, not all of them necessarily for the good, created by that hydraulic pressure from students, circumstances, and Zeitgeist which could bend even well-established principles. By the early 1970s the compulsory side of the BA had almost vanished; what remained was that in the first year one had to take at least one class from three of languages, humanities, social sciences, and sciences.

In April 1969 a committee on examinations urged massive changes in the whole system. Final examinations, it said, put an “inordinate premium on unimportant attributes,” that is,

the ability to organize and recall large bodies of factual material, and the ability to perform mental gymnastics under stress. One of the strongest complaints of students at all levels is that success in final examination depends to far too great an extent on the memorization and reproduction of the material presented in lectures.

The report also criticized the physical conditions under which the examinations were written; it argued that if some students responded positively to stress, if they found “in the sordid squalor of the examination room an almost masochistic stimulus,” most students did not. To say that examinations were useful because they forced students to study was “not legitimate in a University, if anywhere.” Most serious of all, said the committee report, examinations were unreliable as a test of performance or of achievement.

That radical rhetoric from the Committee on Examinations did not move the Faculty of Arts and Science very far. Few faculty members could really jettison examinations in some form as tests for student skills, knowledge, and work, although take-home examinations became more widely accepted. The History Department did experiment with a first-year class in 1972 mounted by two young and talented historians, where the only condition was attendance. It offered a huge melange of the history of the last hundred years which included even all of Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungens. There was no examination and it attracted much attention. After three years, faculty’s impression was that the historians were doing all the work and the experiment was shut down as something of an embarrassment. Many Arts and Science professors looked at the professions, Law, Medicine, Graduate Studies, where stiff written or oral examinations prevailed. That tended to prevent any great liberalization of undergraduate examinations. What did evolve was a greater emphasis on term work, on essays, research, seminars, so that examinations became less horrific in character and consequence. The general view of faculty was, one might as well learn to deal with examinations because sooner or later one was going to need to. That was the unspoken major premise in most of the academic minds that resisted radical proposals.

The most important change in Arts and Science was the increase in the number and quality of staff. Dean MacLean got Hicks’s authority to look for first-class people. It required technique to initiate such appointments, for not all departments welcomed having big names parachuted in. Edgar Z. Friedenberg, famous both in Sociology and Education for The Vanishing Adolescent (1959) and other books, appointed in 1970, was not accepted by Sociology and stayed in Education. The technique was to persuade departments that the ideas came from them. Some stars were named McCulloch professors, such as S.D. Clark in Sociology, Wilfrid Cantwell Smith in Religion. Some were hired to build up a department. Peter Fletcher, hired in 1973 as chairman of Music, was told by MacLean that Dalhousie wanted a Music Department that “made music, not just talked about it.” By 1975 that’s what it had become. In one year alone Dean MacLean added seventy new faculty to Arts and Science, ten of them in one department.[4]

He could do that because he now had assistant deans who could look after many things that Basil Cooke had had to do himself. The shoulders of the assistant deans carried the day-to-day work of the faculty while MacLean did what he was good at, hunting for able people. In 1975 MacLean was appointed vice-president academic, and the new dean of arts and science was James Gray, a scholar in eighteenth-century English writers, especially Dr. Samuel Johnson. Gray, talented, sprightly, and amiable, would be dean until 1980. Thus did Arts and Science grow in the 1970s.

The faculty, or more properly the Arts and Administration Building, had long had a worthy old retainer, Jim Stoker, one of those domestic sergeant-majors who gradually become part and parcel of an institution. He came to Canada from Tyneside in 1929; after working on railways in western Canada, he landed at Dalhousie with his northern English accent largely intact. He and his wife, Margaret Baillie of Lunenburg, did much to give continuity and coherence to the work and living around the A. and A. Building. Stoker retired in 1972, grown grey in forty years of honest and unremitting service.

The Registrar’s Office and the Registrar

A still longer-serving official was Miss B.R.E. Smith, “Trixie” to her friends. Appointed registrar in 1952, she was almost the last working link with the Dalhousie of the 1920s. She had come in 1921, a willowy young woman of nineteen, as secretary, half-time in Law, halftime in Medicine, at $12 a week. She came to work eventually for President MacKenzie whom she much admired, and then to the Registrar’s Office under Murray Macneill. Everyone liked her: benign, hard-working, knowledgeable, and under Kerr long-suffering, for he believed people worked best under pressure. Trixie did not work that way; she did things at her own pace. After hours or on Sundays she would often be found at Dalhousie. Few members of the clerical staff gave more of their time. As students crowded in during the 1960s, her salary fell behind those of other registrars and when she retired in May 1968, her pension after forty-seven years’ work was $267 a month. To that was added the new 1966 Canada Pension and the old age pension. The board raised the university pension by 15 per cent ex gratia, subject to further improvements in the future. That was decent but the least they could do. In 1968 she was given an honorary LL.D., deserved in ways few LL.D.s are.[5]

Technically her successor was H.J. Uhlman, but he was also dean of student services, which was where he concentrated his attention. Peter Griffiths, the associate registrar, really ran the office. Trixie Smith spent considerable effort organizing her thoughts and her records to make Griffiths’s takeover as easy as possible. Her system, inherited from Murray Macneill, was good enough to survive into her successors’ time, although an IBM 360 was added. She even offered to help Griffiths for a while, but he brushed her off. “You just close the door,” said he, “and I’ll take over.” The contrast between Trixie Smith’s meticulous annotations on student records in steel-nibbed pen and ink, and the impersonal computer print-out, sometimes garbled, was palpable.

The office work became garbled too. Griffiths plunged the Registrar’s Office into a computer system without taking sufficient time to gear up for it. Other registrars were surprised to hear what Dalhousie had done; they were taking two to three years to make the conversion that Dalhousie’s new registrar was attempting in as many months.

The senior women under Trixie Smith, Marion Crowell, Faith DeWolfe, Frances Fraser, all of whom shared her views and carried her traditions, were devoted, hard-working, and underpaid. They knew Griffiths from registrars’ meetings, for he had been associated with Acadia. When the news came that he was coming to Dalhousie and that they would actually have to work under him, they were stunned. One went home and burst into tears. Peter Griffiths proceeded to ignore them, indeed shut them out as much as he could from his mode of operation, relying for his principal assistant upon a lady favourite within the office. A busy and important office carries on for a while under its own inner momentum, but its strength and morale is not proof against such arbitrary favouritism. Within eighteen months the Registrar’s Office was almost wholly unstrung.[6]

Not much of this was known outside the office; some departments never divined that there were problems. But morale was sufficiently bad that in the fall of 1970 a president’s advisory committee was struck to investigate, driven by Louis Vagianos, then director of libraries. In December he presented a blistering report on the Registrar’s Office and the Admissions Office. There had been no clear-cut reporting structure, and worse, there were serious personality problems. Vagianos urged a wholesale clean-out of the principal officers, Griffiths in particular. The matter was urgent.

Nothing happened, except that things got worse. Universities do not like firing senior officials whom they have been at some pains to hire; once in place it was decent to allow them time to find their feet. That was how Carleton Stanley survived the 1932 attack of Fred Pearson. By 1972 there were protests by faculty over the operation of the Registrar’s Office. There were protests by junior staff in the office itself. There was talk of resignations. A further report by Vagianos in January 1973 finally brought action. Uhlman resigned on 31 January 1973 for “health” reasons. He recommended Griffiths be kept on as registrar, noting that circumstances had clouded Griffiths’s “untiring efforts” to be useful. But Dalhousie had had enough. Griffiths was out. Vagianos, now director of communication services and general trouble-shooter, thought of a new registrar, preferably someone from within Dalhousie.[7]

One of the professors who had been uniformly helpful to Trixie Smith over many years was J.G. Adshead, head of Mathematics from 1953 to 1965, and for a long time chairman of Arts and Science’s important Committee on Studies. A great teacher, a walking encyclopedia, a marvellous wit, he had been a bachelor all his life. When asked about that, he replied, “I didn’t really start out to be a bachelor. It’s just that as I became more particular, I grew less desirable!” He had known Trixie Smith since he had first come in 1927 and he had long acted as faculty spokesman for, and defender of, her and her office. Thus there had been a traditional connection between Mathematics and the registrar. Vagianos approached Arnold Tingley, chairman of Mathematics, nearing the end of his term as chairman. Tingley looked at the Registrar’s Office, saw a challenge there, and accepted the position on two conditions: one, that the three senior ladies, upon whose loyalty and service so much had depended in the past and who had somehow preserved the office from utter chaos, would stay and work with him; the second that he have a free hand to fire and hire.[8]

Thus did A.J. Tingley become registrar on 1 March 1973, and registrar he would remain for the next twelve years, running the place with integrity, vigour, and common sense. Best of all, his staff stood by him.

The Classics Department and Dr. Bruno Dombrowski

From the beginning Dalhousie had imported talent from the outside. Most of the time it had worked, sometimes brilliantly. But the disruption in the Registrar’s Office was matched by one in Classics, and for analogous reasons.

In 1965 the Classics Department decided that to qualify for giving PH.D. work, it needed to develop studies of the ancient Near East. The head was then J.A. Doull, MA, one of the best-read men in Arts and Science, though not the most popular. He hired as visiting associate professor Bruno Dombrowski, MA Manitoba, PH.D. Basel, to teach Akkadian (Babylonian) history and culture. Three years later the department also hired T.E.W. Segelberg to develop the Coptic tradition.

In 1968 Doull recommended Dombrowski for tenure, but in May 1969 Dalhousie renewed his contract without tenure. Both Dean James and Hicks were opposed to tenure for Dombrowski. There had been examples of his intemperate remarks, bullying a visiting speaker, as he sometimes bullied younger members of Classics, and he could also be belligerent with students. He meant well, but he was abrasive and outspoken. He blamed Doull for his failure to get tenure, believing Doull had double-crossed him. Dombrowski was furious; he now saw his duty as ridding Classics, and Dalhousie, of James Doull.

But the department split on that issue. There were three associate professors, all with PH.D.s, including Dombrowski on one side; there were three junior members, all working toward PH.D.s, and Doull (who did not have one), on the other. Doull had published very little. That was not lost on Dombrowski’s group; they demanded Doull’s removal for several reasons but high on their list was what they called his scholarly deficiencies.

Not surprisingly, the work of the Classics Department, apart from meeting students and classes, stopped dead. Faculty Council investigated, and decided that the Dombrowski group did not have a case against Doull. One professor accepted that verdict and joined the Doull group. But Dombrowski and his colleague Segelberg refused point blank. So the split remained, though now five to two.

Dombrowski’s case for tenure was heard in the fall of 1970 by the Faculty Tenure Committee, chaired by a respected historian, John Flint. The Tenure Committee recommended tenure in forty-three cases, including Dombrowski’s. The president and Dean MacLean accepted forty-two, refusing to accept Dombrowski. There were appeal procedures which Dombrowski proceeded to invoke. In May 1971 an ad hoc committee of the Board of Governors heard his appeal. By then the nub of the issue was his collegiality. The Faculty Tenure Committee had felt that on the whole Dombrowski could work with his colleagues; Hicks and Dean MacLean, who had the right to review Tenure Committee recommendations, felt that Dombrowski could not. The board committee backed the president and dean. In April 1972 Dombrowski was given a final two-year appointment as research scholar, the second year being leave of absence with pay.

He still did not give up. Unwisely advised by a downtown lawyer, he sued Hicks and Dalhousie for his right to tenure. The trial took place in the Nova Scotia Supreme Court in November 1974. The evidence of a senior classicist from England, A.H. Armstrong, now in the Dalhousie Classics Department, who had an unassailable reputation, was decisive. Dombrowski, he said, was an impossible colleague. Justice Hart rejected Dombrowski’s claim for tenure. He was out.

Bruno Dombrowski had vigour and talent but in the end they burned him and colleagues around him. But no one in Classics who lived through those five years was likely soon to forget the experience.[9]

Accrediting the Library School

Hicks was probably right in rejecting someone whose effect on a university department had been disastrous. Thus, if authority and decision had been lacking in dealing with the Registrar’s Office, Hicks could use his power to good effect. He also showed his skill and panache in defending the new Dalhousie Library School in 1972-3. From the beginning Dalhousie wanted a Library School for the Atlantic provinces and it wanted its program, of course, accredited. It was also in a hurry. Many such schools waited five years before asking for accreditation. Dalhousie established its Library School in 1968-9; it asked for and got an American Library Association team of six that came to Dalhousie in March 1972. On 27 June 1972 the Committee on Accreditation (COA) decided against the Dalhousie master of library science program. The chief ground for this rejection were alleged deficiencies in the number of faculty, and an absence of a “native-born Canadian among its fulltime professors.” Apparently Canadians on the COA did not like the lack of Canadians nor calling the degree master of library science. Most other post-graduate degrees in the subject were called bachelor of library science.

There was a right to appeal this COA decision. Rejections had never been appealed before, but Dalhousie proposed to do it. The hearing was set for January 1973 before the American Library Association executive, with the accreditation team present. Dalhousie’s ground for appeal was that the COA had exceeded American Library Association standards in considering Dalhousie. Dalhousie sent four senior officials: Hicks, W.A. MacKay (vice-president), Norman Horrocks (director of the school), and Louis Vagianos. The appeal was held in Washington on 30 January 1973. Hicks, in Washington on Canadian government business, came to the hearing in black coat and homburg. He made a short speech. “Before you start, gentlemen, let me say one thing. If you tell us our program is no good, it will be killed tomorrow. We’re a good university; we don’t want second-class stuff in it.” Hicks won the battle there and then, as it turned out. After the hearing the Library Association executive overruled its COA, and voted to accredit the Dalhousie program as of 1970-1.[10]

That was a surprise. Pre-decision gossip was that Dalhousie did not stand a chance. “After some of the most tortured soul searching we have ever observed,” said the editorial in the American Library Journal, “the University and school decided that their case was worthy of a hearing, despite the odds.” It put the cat among the pigeons at the American Library Association too. The accreditation team were furious and refused any more work. An editorial in the Library Journal praised “the Dalhousie appeal” as showing that the Library Association was making progress towards establishing fairness in its procedures. Perhaps Dalhousie might have won the appeal anyway, but Hicks’s intervention seems to have clinched it.[11]

Graduate Studies

A new dean was to be appointed for Graduate Studies in 1972. There were probably a dozen professors in Arts and Science who could handle the job, wrote one chemist, K.T. Leffek, “and, casting aside false modesty, I would include myself in that dozen.” Hicks liked Leffek and A.M. Sinclair of Economics; but he was reluctant to pull Sinclair out of Economics where he was badly needed; J.F. Graham, the chairman of Economics, was on leave to the Nova Scotia government’s Royal Commission on Education, Public Services and Provincial-Municipal Relations. Leffek was appointed dean in September 1972.

In the meantime the president and Senate Council ordered a review of the whole system of Graduate Studies. The review in December 1972, which drew heavily on the system at McMaster University, recommended that Dalhousie’s Faculty of Graduate Studies be dissolved and replaced with a School, with eight committees appended to it. Dean Leffek, who resisted these McMaster innovations, used an argument from Petronius Arbiter, Roman official in the time of the Emperor Nero: “We tend to meet any new situation by reorganizing. And a wonderful method it can be for creating the illusion of progress while producing confusion, inefficiency and demoralization.”

Leffek thought the Faculty of Graduate Studies was in excellent shape as it stood. He had a first-class group in his office. Only minor adjustments were needed: Leffek believed that standards in Dalhousie’s PH.D. programs would be maintained, even enhanced, by having a senior academic chair a thesis defence in another department. For Dalhousie’s size and scale, that was eminently sensible. The changes were mostly Leffek’s doing, for he and the president had not found a single hour for “an unhurried exchange of ideas… How can we hope to understand a problem, let alone agree on a solution, if we never talk about it?” In the end it was Leffek’s good sense that prevailed, and by 1 June 1974 it was agreed between Hicks, MacKay, Stewart, and Leffek that the faculty would continue in its present form. Moreover, Leffek was right that he was dean material. He stayed on not just for that year but for a further sixteen years, through three deanship reviews, only retiring in 1990. Graduate Studies had not needed reorganizing so much as having common sense and administrative talent applied to it. Leffek devised an excellent staff in his graduate studies office; they repaid him with devoted service.[12]

A New Faculty of Administrative Studies

The confusion that attended the proposed reorganization of Graduate Studies also attended the creation of the Faculty of Administrative Studies. Here one suspects Hicks’s subterranean prejudice against Political Science that went back a decade or more. Creating such a faculty was based on the useful idea of bringing together Business Administration and Public Administration under one umbrella, with benefits to both. The idea came out of York University. It had recently created just such a faculty, with a core program and options towards either Business Administration or Public Administration. It was really an MBA program that with proper options could be made into a MPA one. Most Dalhousie political scientists would have seen it as a form of subordination. The difficulty was that the committee struck by the president did not take sufficient, if any, cognizance of well-established structures in public administration in the Political Science Department. The original committee was set up by Hicks in March 1972 to review the Department of Commerce, its work in business administration and “related studies.” Hicks appointed as chairman C.J. Gardner, Arts and Science administrative assistant, with Michael Kirby and A.J. Tingley of Mathematics. They were to report in six months. It looked like a committee thrown off mercurially by Hicks, perhaps under pressure from Vagianos, Kirby, or both. He ought probably to have proceeded by a slower and more ponderous route, via Arts and Science and Graduate Studies, and included in its terms of reference Political Science’s program of public administration.

The report’s publication was the first that Political Science had heard of the idea and the department hit the roof. A sixty-one-page critique of the report landed on the desk of the secretary of Senate. J.H. Aitchison said: “I have not in my life, even in Dr. Kerr’s day, witnessed a case in which such crass administrative stupidity was shown.” A special sub-committee of Senate Council was set up to study the Gardner Report and report back. It did, in April 1973, largely echoing the views of the first committee. But the issue was so hot that the second report was tabled for a future meeting which took place three months later in July 1973. In the meantime the air was rent with cries of execration from political scientists who were frankly horrified at the cavalier gutting of a good program in their department, putting it under a wholly new faculty. As they saw it, they were being sold to Business Administration.[13]

It was a contest between academics wanting to conserve what was already established in public administration and university officers who believed that a new framework for change was necessary, that the status quo would hinder the development of new specialities. Political Science replied that with consultation and ingenuity it was possible to do both. But once Political Science’s outrage was aroused, it was difficult to persuade it of any merit at all in having a Faculty of Administrative Studies. The professors teaching public administration, Paul Pross, David M. Cameron, James McNiven, were an integral part of Political Science, also teaching classes in Canadian politics and government.

In July 1973 Hicks believed that Political Science was being negative and too inward-looking. A steering committee was now struck to arrange matters; Hicks did not want J.H. Aitchison on it, declaring he would probably want to sabotage its work. K.A. Heard, chairman of Political Science, protested against any such assumption; as chairman of the department, he felt that if it would serve the department’s interest to nominate Aitchison, he would do so. Hicks backed off a bit. “Our views may differ on the usefulness of adding Professor Aitchison to the Steering Committee, but I agree with all you have to say about his integrity and service to Dalhousie University.” In the end, Heard himself and Cameron went to the steering committee, and in the end, too, most people climbed down from outrage and went to work to fashion sensible programs in Administrative Studies. They came up with a federated faculty of several schools: Business Administration, Public Administration, Social Work, Library Sciences. A majority of the committee wanted to call it Professional Studies but the business side disliked that so thoroughly it was left as Administrative Studies.[14]

In April 1974 nominations came in for a dean. Hicks had Michael Kirby in mind, a good choice, and was trying to be patient. He told Lieutenant-Governor Victor Oland, a member of the board, that the five-year principle for deans’ appointments had worked much better than expected. With a few trifling exceptions, Hicks said, “I have managed to have administrators appointed and re-appointed who were acceptable to me.” But with the Faculty of Administrative Studies it did not go like that. The search committee knew Hicks had a favourite candidate; Hicks expected to get his way after a couple of months’ delay. But he didn’t. The search committee was disposed to explore alternatives. So they went to Hicks to find out if any other candidate would be acceptable. Hicks was furious, tore a strip off the committee, telling them that he supported Kirby because he was the best candidate. If the committee did not want Kirby, he was withdrawing the nomination. The committee’s choice, and the new dean, was Peter Ruderman, Harvard PH.D. in economics, who was professor of health administration at the University of Toronto before coming to Halifax. Classes began in September 1975. The creation of the faculty had taken more than three nerve-wracking years. It might have been done in half the time, with more care, more tact, and less impatience. Inevitably the person who had to pick up the pieces, handle the negotiations, was Hicks’s patient, hard-working, cool-headed vice-president, W.A. MacKay.

In this episode Hicks’s weaknesses showed up perhaps more tellingly than in any other. He had always retained a certain animus against J.H. Aitchison, not so much for his 1960 resistance to Hicks’s appointment as dean – that could be passed over – but more for his flat refusal to give Hicks any standing at all in the Political Science Department. Hicks was never allowed to teach a course in political science. Moreover; Political Science had taken a strong stand against Henry James as dean of arts and science, a choice that Hicks had pushed hard. James and his supporters were seen by Hicks as progressives, his opponents as conservatives who opposed change because it altered the status quo. It is altogether probable that Hicks did not set out in 1972 to mutilate Political Science, but he might not have been unhappy had that been the result. He sometimes liked to run hard his authority.[15]

If so, he sometimes knew when it was sensible to avoid doing so. An example of this is his conduct of Dalhousie through the trials and temptations offered by the Nova Scotia government’s wish to establish on the Dalhousie campus a post-graduate Institute of Education.

Atlantic Institute of Education: Its Rise and Fall

The idea behind the Atlantic Institute of Education (AIE) was to focus and strengthen graduate studies in education in a degree-granting body in Halifax, which would cooperate with the other Atlantic universities. With the universities’ help and with a relatively small staff, it could develop an ambitious program that would revitalize teacher education in all the universities. The idea was driven by Robert Stanfield in his double role as minister of education and premier, an idea he seems to have had almost since he took office in 1956. The Nova Scotia Department of Education took it up and in 1964 got it on the agenda of the Association of Atlantic Universities (AAU). The AAU suggested that advice should be sought from outside the province, and Stanfield duly invited Professor Basil Fletcher, of the Institute of Education at Leeds University, to come and report. Fletcher knew Dalhousie; he had been professor of education here from 1935 to 1939, when Stanfield was a student. Fletcher made a flying visit in 1966, and recommended that an Atlantic Institute of Education be established without delay, at Dalhousie’s Faculty of Graduate Studies. Basil Cooke, then dean of arts and science, thought Fletcher was too precipitate by half, and the report too weak on facts and figures to justify such a departure. Nevertheless, Fletcher’s recommendations were accepted by the Nova Scotia government. Stanfield wanted the institute on the Dalhousie campus, as Fletcher recommended, and he wanted it as soon as possible.[16]

One fundamental difficulty was that the enthusiasm of Stanfield and the Nova Scotia Department of Education was not shared by the other three provinces. New Brunswick’s participation was important and Dalhousie tried to persuade UNB to join in, but its deans of arts and science, and graduate studies, were plainly reluctant. Memorial’s Faculty of Education had the largest teacher training program in the whole region and was even more disinclined. And at every opportunity, Hicks deliberately played down any suggestion that there was anything in it for Dalhousie. In December 1967, asked by Berton Robinson, secretary of the University Grants Committee, if he would call a meeting of heads of Education Departments, Hicks said he couldn’t; it would not be wise. He thought it was unreasonable to expect the Nova Scotian universities, to say nothing of Atlantic ones, to rush to support an Institute of Education at Dalhousie. If any movement was to be made, the government of Nova Scotia would have to do it. That the Nova Scotian universities had agreed to accept an institute at or near Dalhousie was all they could be expected to do. Now the government would have to do the rest.[17]

Hicks’s caution reflected his experience as a former education minister who knew the sensitivities; but he also knew that both Acadia’s and Mount St. Vincent’s departments of education were better than Dalhousie’s. Dalhousie students may not have been aware of comparisons, but they did not much like what they saw of education at Dalhousie. The big explosion came on 11 January 1968; most of the Gazette’s front page was devoted to the iniquities of Dalhousie’s Department of Education, using especially Professor B.M. Engel’s Christmas examination in Education Mathematics 4:

QUESTION 3: Which of the following is “twelve thousand, thirty five”: 1235, 12035, 120035, 1200035

QUESTION 31: Which of the following is one-half of 1 hour, 40 minutes: 20 minutes, 45 minutes, 50 minutes, 70 minutes.

The Gazette rubbed it in: both inside and outside Dalhousie its Department of Education was regarded as a farce, a school for morons, a waste of time. “The reputation enjoyed by our Department of Education is something less than enviable.”

That Gazette issue hit the Education Department the next morning like a bombshell. The department’s question, according to the Gazette, was not the accuracy of the facts, but who had written the article? It was said that Professor A.S. Mowat, head of Education, would soon be wiping the smirks off the faces of the students who had. Mowat considered the criticism “almost wholly undeserved and in part dishonest.” He thought no student newspaper should be allowed to print an anonymous statement without being called to account for it, especially the Gazette’s remark that Dr. Engel was “a fool admittedly.” Mowat thought some effort should be made to discipline the writers concerned. Hicks was sympathetic but believed that any attempt to punish those responsible at the Gazette would give the students a fine opportunity to mount a crusade. Besides, he said, “a strong and competent Department is on solid ground in ignoring such student comment.”[18]

But the ground was not solid. Three months later a questionnaire conducted on his own initiative by Peter Robson (’68 B.Ed.) asked some three hundred B.Ed. graduates from 1965-7 what they thought of their courses in education. Robson received sixty-six replies. The questionnaire had for answers five categories: very valuable; quite valuable; useful; slightly useful; of no value. The majority of replies agreed with the last two categories. Percentages of the replies in the two lowest categories were[19]:

Of no value Slightly useful Total % % % History of Education 45 31 76 Philosophy of Education 42 22 64 Methods 45 40 85 Educational Psychology 23 28 51 Testing and Measurement 18 37 55 Practice Teaching 2 22 24

A.S. Mowat had come from the University of Edinburgh in August 1939 at the age of thirty-three, to take the O.E. Smith chair in education at $3,800. He had largely created the Dalhousie Department of Education, set its standards, chosen its professors. He was a decent man with a pawky sense of humour, who had long served as secretary of the Faculty of Arts and Science. But for almost as long, the Department of Education had been the step-child in the faculty, its programs at best tolerated rather than respected. Dean James was less than tolerant. In July 1968 Mowat handed in his resignation as head, effective 31 May 1969. The front-page criticism of the Gazette had been too much.

The government believed that teacher education needed sprucing up. The Chronicle-Herald of 18 April 1968 noted that enough had been said in the papers to warrant a thorough review of teacher training programs. The government acted as soon as possible. After some difficulty in finding the right man as director Dr. Harold Nason, deputy minister of education, nominated a friend of his who was retiring as dean of the University of London’s Institute of Education, Dr. Joseph Lauwerys, a Belgian long time resident in Britain. Lauwerys was friendly, affable, full of ideas (not all of them relevant), but he knew nothing of the region and little of the situation he would be getting into. He was also old, though not, as rumour soon had it, too old for everything! He came and reported. His report seemed to have only a remote relevance to Nova Scotian and Atlantic provinces realities. It reminded one Dalhousie historian of “the dreary papers which the British Colonial officials in the more backward islands of the West Indies used to send to the Colonial Office in the 1930s, bemoaning the fact that nothing could be done.” He suggested that all that Lauwerys’s proposals did was to add another layer of cumbersomeness to a situation already replete with it. As Dean James pointed out, it was difficult to separate Lauwerys’s ideas from the exhortatory language in which he expressed them.[20]

Despite these warning signs, the government, now with G.I. Smith as premier, plunged ahead. The Atlantic Institute of Education was duly chartered in 1970, with a board of directors. It got modest premises at 5244 South Street. Hicks did his best to soften the resistance of the Dalhousie Department of Education. He told Stuart Semple, acting chairman after Mowat’s retirement, that now the AIE existed, “we must try to make as much use of it as we possibly and properly can.”

Lauwerys for his part found that the Dalhousie Library in Education had “extraordinarily poor and limited resources.” That might have been ascertained earlier; it was of a piece with the generally superficial appraisal the whole project had received. An Academic Council had to be set up to advise the AIE board and finally, in December 1973, the AIE began to grant degrees. Lauwerys retired in 1975 and Professor W.B. Hamilton, a Nova Scotian recruited from the University of Western Ontario, became the director. By this time, however, the AIE was in difficulty.

There had been several mistakes. One was to call it what it was not. Atlantic Institute of Education might well have been what the Nova Scotian government would have liked, but the other three provinces were massively uninterested. New Brunswick had already rationalized teacher education; what Nova Scotia chose to do with the departments of education in its many universities was Nova Scotia’s problem. Moreover, the AIE’S degree-granting powers were a threat, a tacit acknowledgment that the university departments of education needed strengthening. But the senior personnel of AIE were not reassuring, especially Lauwerys and his brilliant but abrasive assistant, Gary Anderson, a recent Harvard PH.D. As Peter McCreath (’68) remarked in the Chronicle-Herald on 3 June 1976, Lauwerys and Anderson had been an odd combination: “While Lauwerys confounded all with his congeniality, and his unending list of ideas, Anderson scared all with his caustic wit and rapier-like mind.”

After 1975, however, strenuous efforts were made by W.B. Hamilton and his new assistant, Andrew Hughes, to redeem the original mission of the AIE. Hamilton was a good choice, but in the autumn of 1975 as he made the rounds of Maritime universities, he began to wonder if he made a mistake in taking on the AIE. One of his first visits was to Hicks, who as usual was candid to a fault. He told Hamilton that the only way Hamilton could get cooperation from the universities was to get them involved in AIE’s administration. In due course that indeed was done; the Academic Council, AIE’s second tier, developed representation from all provincial universities. Hicks also helped to bring AIE into the Association of Atlantic Universities in 1976. The Regan government was encouraging, not Regan himself so much as successive ministers of education such as Peter Nicholson, William Gillis, and George Mitchell. By 1978, just as things for AIE were looking more hopeful, the Regan government was defeated in the general election. John Buchanan’s Conservative government was distinctly unsympathetic and in August 1982 abruptly pulled the plug on the whole institution.

The rise and fall of the AIE reminded one of the fate of the University of Halifax, one hundred years before: a useful idea, badly implemented, followed by a struggle to retrieve it, and finally caught up by politics and destroyed. The massive rationalization of Nova Scotian university education departments effected in the mid-1990s, although its motive was fiscal rather than educational, does suggest that Stanfield’s dream of an Institute of Education might have been right after all.[21]

The Failure of a New Dalhousie-NSTC Initiative, 1969-75

Dalhousie and the Nova Scotia Technical College found each other irresistible, and despite impediments thrown in their way, agreed to a trial affiliation for five years, which began on 1 September 1969, with representatives on each other’s boards and senates. To assuage the nervousness of other universities, Arthur Murphy of the University Grants Committee said in 1969 that no grandiose university such as the University of Halifax, or a University of Nova Scotia, was contemplated. There was even talk of an integrated engineering program for Halifax that might include Saint Mary’s. The love affair continued; in November 1972 the Faculty of Engineering at NSTC recommended the integration of Dalhousie and NSTC. By 1974 it had been approved by both senates in principle and successive drafts of agreements were being discussed at Dalhousie and NSTC. Cabinet approval for the principle had been obtained, and by the late autumn 1974 it had got to the stage of legislation when bills 110 and 111 went to the Law Amendments Committee. But the Chronicle-Herald weighed in, opposing the idea root and branch. It claimed that the Dalhousie-Tech merger would establish one Nova Scotian university to which all the others would become just affiliated colleges. That was, indeed, the way the other colleges perceived the merger. The Law Amendments Committee promptly gave the bills the three-months’ hoist and that ended their life for 1974-5. While Dalhousie expressed the hope that initiatives at Province House would resume in 1976, in fact the Dalhousie-NSTC merger was off. The Regan government could not face the political consequences. In 1996 a later Liberal government, bent on saving money, would face them more ruthlessly.[22]

Trying to Get a New Building for Dentistry

The Nova Scotian government was also resistant to putting up the substantial money to expand Dentistry, perhaps more so under G.I. Smith, Stanfield’s successor, and the Liberal administration of Gerald Regan. Dentistry as faculty had always had a difficult time finding money. When Dean J.D. McLean came in 1954 the whole Dental School was five rooms in the south end of the Forrest Building. He was the faculty plus a dozen part-timers, all of whom had dental practices and were paid a pittance by Dalhousie. Dentistry was not in the public eye and never had the same transcendent importance as Medicine. For that reason it was much harder to persuade governments to support it. Yet it was also more expensive, per student, to run. Fulltime professors of dentistry were not easy to acquire either; university salaries could not equal what a good dentist earned in private practice. J.D. McLean shouldered this tough burden. He brought to fruition the new Dentistry Building of 1958 costing $1,019,000, to which the government contributions were less than 25 per cent. Most of that expense was on Dalhousie’s back.[23]

McLean was vigorous, trenchant, and outspoken. He did not suffer fools much, and he could be rough on students. He could be hard on staff too, and one of the difficulties in getting and keeping staff might perhaps have been Dean McLean. Nevertheless by 1967 Dentistry had fifteen full-time staff and thirty-one part-time. By then it was necessary to rethink the philosophy and scale that dictated the size of the 1958 building. The Tupper Medical Building influenced Dentistry, fostering ambitions and raising hopes.

Nova Scotia was under-supplied with dentists. As late as 1966 the three eastern counties of Guysborough, Richmond, and Victoria had no dentist at all. Four others – Cumberland, Pictou, Hants, and Shelburne – had dentist-to-population ratios of worse than 1:10,000. Other Atlantic provinces were as bad or worse. Dalhousie, studying those figures, projected it would need to bring in sixty-four dentistry students a year and sixty-four dental hygienists. That was too ambitious, and it became an issue between Dean McLean and the Atlantic region dental associations. They did not want that many dentists! If Dean McLean was stubborn and intractable (as Hicks said), dental associations could be too.[24]

Dental building specialists from Detroit came in 1966 and plans were sufficiently advanced that Stanfield, who saw them and the projected cost, blanched. He protested in March 1967 that $11 million was a lot of money; was the Dental School trying to emulate the Tup-per Building? By Stanfield’s arithmetic, if the Tupper Building started out at $5 million and became $18 million, what would a dental building that started at $11 million become? He found McLean’s figures “a little frightening.” Do urge your people, he told Hicks, to be realistic, for “financial necessity will compel the province to be pretty tough.”

Dean McLean made the point, rightly enough, that any comparison between Medicine and Dentistry was misleading: the teaching hospitals provided medical students with their teaching facilities, but Dentistry had to fund and operate its own clinic for teaching. The reason, moreover, for the very great increases in costs was that in the 1950s it cost Dalhousie $1,100 per dental student. It was now, in 1967, over $6,000.

Hicks told Stanfield that Dalhousie would make no move whatever without the government being fully informed. “I am a firm believer in as large a measure of independence for the universities as possible, but this [Dentistry and Medicine] is one area wherein I am totally convinced that a private university cannot move without complete cooperation of the Government of the area it is serving.” Hicks was not at all sure he liked what McLean and the Detroit planners were doing. By July 1967, when the Medical Building was just being opened with all the fanfare, Hicks, discouraged about dental prospects, told Stanfield to explore “all possible alternatives, even to the extent of having someone else take over dental education from Dalhousie University, if you and your colleagues believed there is any more economical way to serve the needs of Nova Scotia and other Atlantic Provinces.” The difficulty of getting four governments to agree on sponsoring Dalhousie’s dental needs made for slow and rough going.[25]

The site of the new building was to be on the south side of University Avenue between Henry and Seymour Streets. J.D. McLean held to that site with tenacity. Hicks later said the new dental school would have been ready two to three years earlier if the dean of dentistry had been more flexible. Building it was still not on track when Dean McLean resigned as dean in 1975 at the age of fifty-five, in truth because he did not get his way. He had built the Dental Faculty of the 1960s; he had also instituted the teaching of dental hygienists, the first class of three graduating in 1963. But in 1975 students were still entering Dentistry at twenty-five per year, an admission rate that only just kept pace with natural attrition of practising dentists. Since 1962 Dalhousie had only been able to accept 363 of 1,355 qualified applicants; there was no room to accept more. The Chronicle-Herald pointed this out in February 1976.[26] By that time proposals for a new dental building had already taken ten years. Dentist/population ratios did not improve. Dental authorities claimed the ideal ratio was 1 dentist per 1,000 population. In the United States the ratio was 1 to 1,300; in Nova Scotia it was 1 to 3,600, and in Newfoundland 1 to 5,000. It was bad arithmetic that none could take pride in.

In October 1976 Dr. James McGuigan, president of the Nova Scotia Dental Board, made an appeal to the Dalhousie board executive, meeting jointly with Senate Council. To qualify for federal funding, the new dental building had to be ready by the end of 1980, but getting agreement among four Atlantic province governments and the federal minister of health had proved very difficult. It was made more so by the fact that provincial ministers of health, as McGuigan admitted ruefully, “seem to change portfolios as frequently as Elizabeth Taylor changes husbands.” They still hadn’t agreed at the end of February 1977. Last-ditch meetings between Dalhousie and the Nova Scotia and New Brunswick ministers of health were scheduled. Should Dalhousie launch a public appeal – “everything else having been tried”? It wore an air of desperation.

There were now hints that a new dental building might have to be added on the existing one. It was in fact on that basis that in April 1978 a new dental complex was put together, with contributions as follows:

Health Resources Fund (federal) $13,319,222 Atlantic Provinces 6,180,778 Dalhousie (contribution of land and building) 2,465,000 Total $21,965,000

The new dean of dentistry, Ian C. Bennett, was largely responsible for breaking the deadlock. The new building was designed in-house, as was construction management.[27]

The new structure took the form of a substantial addition to the existing three-storey 1958 Dental Building, and it would in fact contain four times as much space as the original. Blasting began in June 1978 and went on for some months. At last, in June 1982, the new Dental complex opened. Annual admissions would not be sixty-four dentists and sixty-four hygienists, but a more modest forty-eight of each.

Changes in the Faculty of Medicine

The Medical Faculty calendar for 1973-4 listed as professors on the roster of 1972-3 some 440 at various levels and a dozen preceptors, some 20 per cent more than all of Arts and Science. True, only one-third of the professors in the Medical Faculty were full-time; nor were they all in Halifax. There were about sixty teaching in Saint John General Hospital, another three in Moncton, with a clutch of preceptors scattered over the Atlantic provinces – doctors who taught interns out of a private practice. But even when those outside of Halifax were deducted, the Dalhousie Medical Faculty in Halifax was still a substantial professoriate of about 375.

This was the faculty that Dean Chester Stewart had developed since he had taken office in 1954. That was one of his major legacies to Dalhousie; another was a string of good appointments; and the third was the handsome Medical Building, the idea behind which was basically his. Much of the detailed work that had gone into it, however, was Dr. Lloyd Macpherson’s, the assistant dean in the 1960s. The medical staff at Dalhousie may have underestimated Stewart’s contribution; the younger ones felt the pressure to introduce the five-year rotating deanship established in Arts and Science. Should there not be a new dean of medicine, one less authoritarian and more flexible? In 1971 Chester Stewart was only sixty-one years old; although he had been dean for seventeen years, there seemed to be lots of deaning in him yet. But he had never worn his authority lightly, and his faculty were beginning to chafe. There was no sign of his retiring; he and his colleague Dean J.D. McLean of Dentistry both sailed serenely on. The principle that when assuming an office one should contemplate the resignation of it did not seem to concern either dean. So the Faculty Council of Medicine acted; they went to Dean Stewart, some more outspoken than others, and said there was a substantial feeling that it was time for him to step down. He resigned as of 1 July 1971, and almost at once was promoted to vice-president of health sciences, a useful role for a retiring dean. Dr. Lloyd Macpherson was made dean until a new one could be appointed.[28]

That was not so easy. Others outside Dalhousie thought Stewart would be extremely difficult to replace. Dean Douglas Waugh of Queen’s believed Stewart had served “with dedication and ability that are not fully appreciated by all of its [the Faculty’s] members.” So also said Dean W.A. Cochrane of Calgary. A search committee was duly elected, chaired by John Aldous of Pharmacology. Several candidates were suggested: internal ones were Richard Goldbloom, head of Paediatrics; John Szerb, head of Physiology; Ross Langley of the Department of Medicine, as well as some external ones. The internal ones bowed out, Goldbloom with particular grace: “Underneath the thin academic veneer, I am just a children’s doctor whose greatest single satisfaction comes from the daily contact with children and their families. I am simply too selfish to give up this extraordinary source of satisfaction.”

One external candidate, Dr. E.D. Wigle of Toronto, came to Halifax with his wife in March 1972, but he bowed out too; the financial sacrifice in changing houses from Toronto to Halifax was too much. In the end the search came to nothing, and the Medical Faculty in July 1972 were well content to confirm Macpherson as dean of medicine, setting his term to 30 June 1976. That was the end of indefinite terms for medical deans, and that suited Macpherson. He was an excellent dean, his PH.D. an advantage, rather than other wise. He was humane, and he paid attention to students, something not all senior administrators had time for. His faculty even had an opportunity to debate the faculty budget; that was new. Nor did he glory in power; he saw the deanship as duty and self-sacrifice, not as personal aggrandizement. He also took the view, hovering inarticulately in the faculty for some time, that it had responsibility for doctors’ education “from the day he arrives in medical school until he ceases to practice.” Continuing education was important everywhere: it was vital in Medicine.[29]

Dalhousie Medical School had one other characteristic that Macpherson noted for the accreditation team of April 1973. For many years it was the remaining bastion in North America of university-controlled internship. Dalhousie believed that when interns passed under the sole control of the hospital their education was largely neglected. That interns were to work not learn was a prevalent hospital philosophy. The Dalhousie degree was five years, the intern year still being included and controlled. As a result of changes in the 1960s in medical education across Canada, Dalhousie found itself in the van rather than odd man out. In 1974 the Maritime governments agreed to fund the intern year, and Dalhousie could join other medical schools in awarding the degree at the end of four years. June 1974 thus saw two medical classes graduating at once, those finishing the five-year program, and those finishing the four-year one, all of the latter going to university-controlled internships, but clutching their MD degree.[30]

In May 1974 Macpherson set in motion procedures for finding a successor. The search committee took its time; finally at the twenty-fifth meeting on 8 May 1975, the committee recommended G.H. Hatcher of Queen’s. He agreed to come as of March 1976. His term would be seven years; too much work had gone into his selection! The result was worth it; Hatcher was a powerful dean who took immense pains to drive forward the research of his faculty.[31]

In 1974 Robert Dickson retired. He was finding the going more difficult, getting two hip replacements, and finding his administrative work an increasing drain on his time with patients. Out of his work in 1962 for the Glassco Commission on northern health had come the impetus for Dalhousie’s program of outpost nursing. Out of medicare (1969) came a Department of Medicine Research Fund using surpluses of medicare income. When he was president of the Royal College of Physicians, from 1970 to 1972, Dickson was on committees formulating the qualities of good resident training. Dickson insisted on, and got, “compassion” included in it. He explained to the Dalhousie medical graduates of 1980:

Compassion and scientific medicine… complement one another. The first words of a doctor when he has made a diagnosis of a serious disease for which curative treatment is available – if he is a wise and compassionate man – are words of explanation and reassurance. And lo before the first medicine has been given the patient feels better. And it takes so little time to make the difference between “competent physician in a rush” and the “competent and compassionate physician”… So take a moment and do not fear to be involved.[32]

Dickson’s memorial, the Robert Clark Dickson Centre, a $12 million building for ambulatory care and for oncology, was put up by the province and named in his honour. It opened in 1983; a year later Dickson died of a stroke.

Changing the Law School

In 1963 the Law School had fewer than a hundred students. The class of 1963, for example, started in 1960 with thirty-two students in its first year and ended with twenty-two in its third. The flavour of the place was like that of the 1920s and 1930s, virtually every class a seminar. There were nine full-time professors, all but one of those a Dalhousie graduate. When the Weldon Building opened in 1966 there were ninety-four students in the first year, and they so outnumbered the third year that the old tradition of the first year taking its tone and ethos from mature students of the third was dissipated and probably lost. By 1972 there were four hundred students in all and over thirty full-time professors, the outsiders by now much out-numbering old Dalhousians.[33]

The dean of law in 1964 after Horace Read’s departure to the vice-presidency, was W.A. (Andy) MacKay, son of R.A. MacKay, Dalhousie political scientist from 1927 to 1946. MacKay, thirty-five years old, quiet, cool, dispassionate, thorough, was well suited to the Law School with the big changes in staff and students already in train. MacKay became vice-president himself after Read’s retirement in 1969. By then the new mode of choosing a dean, by a committee of senior faculty, already in evidence in other parts of the university, was brought in. Internally, no one wanted to be dean, none at least whom the committee thought acceptable; an outside appointment split the committee. In the end a senior faculty member, R.T. Donald, was appointed caretaker dean. Donald was an expert in corporate law and two years short of retirement; he carried a big load, especially with a law curriculum with many more options than the old, virtually compulsory one.

The major innovation in Donald’s time was a product of law students’ initiatives, the Legal Aid Clinic. Students were concerned about the number of people who were appearing in magistrate’s court without any legal advice at all, not being able to afford it. With a five-year grant from National Health and Welfare, and cooperation from the Nova Scotia Barristers’ Society, the Legal Aid Clinic was opened on Gottingen Street, using third-year law students and the expertise of Mr. Justice V.J. Pottier, retired Supreme Court judge and general adviser. It was Pottier who calmed the Bench, and that meant too that the Bar would not make too much objection to what was, in effect, a store-front law service, unknown at the time. For the law students it was valuable experience: “For many law students it is the first and perhaps the last opportunity they will have to be sensitized to the needs, legal and otherwise, of that very large part of the population that does not customarily enter a lawyer’s office.”[34]

By 1971-2 there was a substantial influx of women law students and by 1976 they were a quarter of the total. By that time the Faculty Admissions Committee were forced to decide how many Nova Scotian, Maritime, and Canadian students would be admitted. It was settled that of the 150 places available in the first year, 60 per cent would be for Nova Scotians, 15 per cent for other Atlantic provinces students, and 25 per cent from elsewhere (nearly all Canadian). That proportion was not the Law School’s decision, however; it was the result of political pressure from Premier Gerald Regan. He said, in effect, “I want 60 per cent of the new students to be Nova Scotians.”

It was not the last time Premier Regan threw his weight around. When Gordon Archibald’s appointment to the Board of Governors was renewed for six years in 1975 it reminded Regan that he did not want to have two strong Conservatives in senior positions on the Dalhousie board, McInnes as chairman and Archibald as vice-chairman. Archibald stepped down. After Regan was defeated by Conservative John Buchanan in September 1978, Archibald, on Hicks’s initiative, was reappointed and would become chairman on McInnes’s retirement in May 1980.[35]

Dean Donald died suddenly in October 1971. It so happened that an associate dean, Murray Fraser (’60), had been appointed in September; at the age of thirty-four he stepped into Donald’s shoes while the search began for a new dean. Ronald St. John Macdonald came in 1972. He was born in Montreal, studied at St. Francis Xavier, Dalhousie, London, Harvard, and Geneva. As that provenance suggests, he became a specialist in international law and came with a wealth of experience, having taught at Osgoode Hall and Western Ontario, and was dean of law at the University of Toronto when Dalhousie persuaded him to come east again. At Dalhousie the news of his appointment created a certain xenophobic unease; who knew in what directions such an outsider might take the old Law School, especially with those credentials in international law?

They need not have worried. Macdonald insinuated himself deliberately, pleasantly, into the Law School, not masking his penchants but, like Horace Read, being willing to listen to what others might say of them. He had been editor of the University of Toronto Law Journal and it was not surprising that the Dalhousie Law Journal appeared in 1973. It was a journal by professionals for professionals, with an editorial committee of four professors, two students, and Dean Macdonald himself as editor.[36]

The Dalhousie Law Library, which in the 1950s had been appalling, had been changed out of all recognition by Dunn money and by Eunice Beeson, the Sir James Dunn law librarian. She was also one of the leading lights in the founding of the Canadian Association of Law Librarians. She died, too soon, of cancer in 1966; it took five years to find her replacement.

The Dunn scholarships had by this time been going since 1958, seven of them at $1,500 each, raised to $2,500 in 1967, and renewable for the second and third year. Lady Beaverbrook took an active personal interest in the Dunn scholars, reading the files of candidates whom the faculty recommended. She expected and received reports on post-graduate awards that her Dunn scholars won. She expected high standards all round. So much did the Law School follow them that it was not until 1968 that all seven Dunn scholarships were awarded. Suddenly in 1973 she discontinued them. She felt that the frequent non-renewals from the first to second year were a signal that the students were not quite up to the mark. Besides, she told Dean Macdonald, none of the Dunn scholars had matched the record of her husband![37]

While this was disappointing, the Law School had by that time developed a substantial outreach in publications. The new law teachers of the 1970s put old styles behind them. One old style had been teaching, not writing. Dean Read used to say that 95 per cent of what was published in the journals was a waste of time, the reader’s and the writer’s. That was certainly a prevalent view at Dalhousie in the 1950s. But Dean Macdonald, a prolific writer himself, soon made it known that he liked to see his faculty in print.

From Toronto Macdonald brought Douglas Johnston, active in international and in marine law. The grounding of the tanker Arrow on Cerberus Rock in February 1971, and the resulting oil spill, sharpened perceptions about environmental issues. Johnston acquired as assistant a young law student, Edgar Gold, who was clerk to the commission investigating the Arrow disaster. Gold was doing research at the University of Wales when Dean Macdonald invited him back to strengthen the Marine Environmental Law Program (MELP). This innovation was followed by the Canadian Marine Transportation Centre (CMTC) brought into existence by Vice-President Guy MacLean, and funded by CN. Within Dalhousie it was free-standing, only indirectly connected to the Law School, reporting to Guy MacLean. The CMTC was soon headed by Graham (later Sir Graham) Day. MacLean thought such institutes and centres extremely useful; they attracted research money and would do things that were not a priority of mainline departments. The Centre for Foreign Policy Studies, for example, an off-shoot of Political Science, received substantial outside funding ($750,000) from the Donner Foundation for research and new staff. Granting organizations rather like the narrow, practical focus of such centres. At Dalhousie, too, they tended to feed one another. Thus by 1977 MELP and CMTC, together with the Institute for Environmental Studies (originally founded by Ronald Hayes) put together a major research initiative that in 1979 won a $1 million research grant from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council for a five-year study of the law of the sea, marine pollution, and Georges Bank.

With Dean Macdonald’s MELP initiatives came others. He made Dalhousie’s international law section into one of the most important in Canada. He initiated exchanges with the civil law schools at Laval, Sherbrooke, and other Quebec universities. He began exchanges with the University of Maine. Ronald Macdonald looked outward, beyond Mauger’s Beach lighthouse to the wide horizons of sea and the lands that lay beyond.[38]

he Law School’s relations with the administration were relaxed and easy in these years. Dean Macdonald was an admirer of Hicks; that was not the only reason he came to Dalhousie, but it was certainly one of them. As to budgets, in those palmy days they were simple. With the current budget in hand, Dean Macdonald once a year went up to see Guy MacLean, and in forty-five minutes over coffee they had the new one mapped out. This informality over budgets could not last after the Dalhousie Faculty Association (DFA) became the professors’ bargaining agent in 1978, but the attitudes behind it did. H.W. MacLauchlan who came in 1983 (out of Prince Edward Island, UNB and Yale), remarked on the ethos he found:

The distinguishing features of Dalhousie Law School are still the nature of the student body, the sense of common purpose, and, I might add, decency… But there is a civility about the place that is not to be gainsaid… Halifax is a decent place in which to live. In fact, more and more people tell me that it is one of the most interesting and most livable places in the country.[39]

Dalplex, the Physical Education Complex, Part 1

What made Halifax a good place to live in was sea, lakes, trees, and neighbourhoods. Dalhousie had not contributed much to the last. It had pushed its way outward for a decade, swallowing up houses, making old properties into new edifices, converting others from family homes into departmental offices that operated only forty hours a week. This continued assault on south-end ways of living from 1963 to 1973 had sensitized residents. And City Hall with them. Hicks had never been particularly tender about public opinion; what Dalhousie needed, Dalhousie wanted and took. Was Dalhousie’s importance as a public institution to be stunted by mere private concerns? To one lady on Larch Street Hicks wrote in March 1974:

… it is easy to blame Dalhousie, as a large landowner in the centre of the city, for a situation which is developing all over the Halifax peninsula. As the city grows, it is more and more difficult to maintain, on this peninsula, the kind of single-family dwelling and the life style accompanying it.

There may have been truth in that, but Hicks would not make many friends by emphasizing it. But then, he was never a good hypocrite.[40]

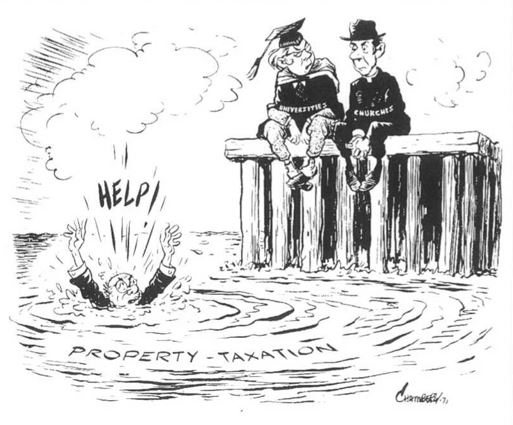

City council was also concerned with the continued conversion of taxable private property into non-taxable (or only partly taxable) university property. Under the Nova Scotia Assessment Act the property of every college and school was exempt from tax, with the exception of property used for commercial, rental, or non-educational purposes. Dalhousie official residences on campus were not taxable; the president’s house was, as also were parking lots, land held for development, itself. In January 1973 the city council proposed to classify Dalhousie parking lots as commercial property and subject them to business occupancy tax. Hicks protested to the minister of municipal affairs. Halifax wanted to go further and tax all university property, but the Nova Scotia government refused to countenance that until the federal government accepted the principle that municipal taxes were a legitimate part of university expenses, and until the Nova Scotia government had received and digested the findings of the Graham Royal Commission on Municipal Government.

In 1973 Dalhousie held property with a total assessed value of $75 million. Only about 11 per cent of that was taxable: Fenwick Towers; Ardmore Hall, a women’s residence at North and Oxford Streets; Peter Green Hall, the married student housing on Wellington Street; and numerous parking lots and houses. Still, Dalhousie’s tax bill was already $250,000 a year. Nevertheless, from the council’s point of view, to have 89 per cent of Dalhousie property wholly exempt was a fairly substantial deprivation of potential revenue. Thus the city council taxed every scrap of Dalhousie property it could construe as not used directly for educational purposes.

Naturally Hicks fought against that and naturally he had few friends at City Hall. Thus, when the massive quarrel arose in the 1970s between Dalhousie and its neighbours over what was called the Physical Education Complex, the outrage of the south-end residents found solace and support on city council, and a witches’ brew of indignation began.

Dalhousie had long needed space for athletics. Since 1932, when the gymnasium was rebuilt, the only substantial addition to Dalhousie’s athletic facilities was the rink in 1950. In those forty years since 1932 Dalhousie’s student numbers had gone from 900 to 7,500. Behind Dalhousie’s renewed interest in athletics was a president who believed in it, but also a solid push from the Nova Scotia Department of Education looking for teachers of physical education. Senate established the Bachelor of Physical Education in 1966, and from that developed the School of Physical Education under the fine work of a zesty Australian, Allen J. Coles, within the Faculty of Health Professions. By 1969-70 it had eighty students and by the following year had developed graduate work. This was some distance from the philosophy that Senate formulated in 1962, that Dalhousie athletics was “recreation not triumphs.” There were also some advantages in the long delay in getting these programs going; it allowed Dalhousie to profit from others’ experience.

Coles was not pleased, however, when Acadia announced in 1969 that it would start a four-year program from Grade 11, saying it had more facilities than Dalhousie. That was true; Studley field was a football pitch, and the gym was small and crowded. But Dalhousie had begun to acquire properties south of South Street, and by the end of the 1960s had a substantial seven acres of land, all of it zoned R2 for institutional and recreational use. With that as a base, Dalhousie began to make plans for a big new athletic centre, and on 6 August 1973 developed its ideas at a public meeting. Hicks and other Dalhousie officials were wholly taken aback by the violence of the reaction against the proposal. They withdrew their ideas, regrouped, and in the fall went on to apply for a building permit.[41]

The south end citizens regrouped too, forming the Committee of Concerned Dalhousie Area Residents (CDAR), and successfully petitioned residents of the sixteen city blocks around Dalhousie to have the lands Dalhousie proposed to use rezoned from R2 to R1, residential. That would neatly end Dalhousie’s plans. But, as Eleanor Wangersky pointed out in the Mail Star, if the move to block Dalhousie should succeed, Dalhousie would sell the land to a developer. Then it might well be rezoned again in a juicy land assembly deal. How about, she suggested, a nice high-rise? Surely Dalhousie’s athletic complex, that children could use, was much better. City council called a public meeting at St. Francis School on 17 October. Five hundred residents attended and another hundred wanted to get in, with both Dalhousie and CDAR conducting a publicity war in advance of it. Hicks, who was not there, was heaped with abuse. An old lady complained of “bearded, barefoot men” in the houses Dalhousie already owned. On the other side Laura Bennet, wife of Jim Bennet, asked what would CDAR do if Dalhousie were to donate the land for low-cost housing? This was greeted with a roar of disapproval from local residents. But at that public meeting Dalhousie lost.[42]

City council had the athletic complex on their agenda on 25 October and again on 15 November. At that meeting it voted seven to three to rezone the Dalhousie land from R2 to R1. Hicks laid blame on the Dalhousie Gazette for an ambiguous headline from which the local newspapers extracted the wrong meaning. But privately Hicks also blamed himself. One night late that autumn Jim Sykes, the university architect, was surprised to get a 1:30 AM phone call from the president. Would he come over and talk? Now? They had always got along well. Sykes knew how to get around Hicks: never let him be in a position to give a positive refusal. Withdraw the issue before that happened. Sykes arrived to find Hicks rather distraught. “Should I resign as president?” Hicks asked bluntly, “I’m not the best Dalhousie representative.” Sykes replied, “Just back off the sports complex. It’s much better than changing presidents.” The process of backing off became in effect a slowing down, enjoined by legal processes.

Dalhousie’s lawyers got to work on how to reverse the city council decision. The precedents were not promising. Donald McInnes related how one of his lawyers brought in a whole pile of precedents – all the wrong way. McInnes flared up. Usually so careful about books, he swept the whole lot on the floor. “Go find some other law!” They did. McInnes was not upset with the petitions against Dalhousie. “You can get people to sign a petition for their own hanging!” was his dismissal of that issue. So an appeal was mounted to the Provincial Planning Appeal Board against such spot rezoning, asking for a writ of mandamus to compel council to issue a building permit. There were suggestions from Mayor Walter Fitzgerald that perhaps the city council might help Dalhousie find somewhere else, but alternative solutions were much more expensive and much less satisfactory.[43]