15 In the Fast Lane: C.D. Howe, Lady Dunn, and Others, 1957-1963

C.D. Howe becomes Dalhousie’s first chancellor, 1957. Lady Dunn and the Sir James Dunn Building. Changes in the Law School. Howe’s dissatisfactions with A.E. Kerr. Lady Dunn’s legacy. Mrs. Dorothy Killam. Howe’s contributions to shaking up Dalhousie. Henry Hicks as dean of arts and science, 1960. Kerr’s resignation, 1962-3.

On Monday, 10 June 1957, to his own chagrin and others’ surprise, Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent and his Liberal government were defeated in the federal election. It broke a Liberal regime in place since 1935. The architect of that debacle more than anyone else was the cabinet minister who had been there since 1935, Clarence Decatur Howe. Nine Liberal ministers lost their own ridings; Howe lost his in Port Arthur, ousted by an NDP school teacher, Douglas Fisher. Howe had thought about getting out of politics in 1955 while the going was good; now he was kicked out. Still active at seventy-two years of age, he did not like it. The new Conservative government of John Diefenbaker was sworn in on 21 June, and it had an ineradicable belief that after twenty-two years of Liberal rule the public service, especially its senior ranks, were badly diseased with incurable Liberalism. For Howe, Ottawa was now insufferable and lonely, his public service friends keeping him at a discreet distance.

In July 1957 Howe gloomed his way down to his summer home in St. Andrews, New Brunswick. St. Andrews was not unlike Nova Scotia’s Chester, Maine’s Bar Harbor, Quebec’s Murray Bay – a summer refuge of the rich, its social life a round of sailing, golf, bridge, and cocktails. There had long been a clutch of acquaintances in St. Andrews, richer than himself, Isaac Walton Killam and Sir James Dunn among others. The relations of Dunn and Howe had been frosty during the first years of the war, but by 1947 they had warmed to each other, and in 1953 travelled to the coronation of Elizabeth II together. There is a striking photograph of the Howes and the Dunns at a coronation reception, the ladies in tiaras, Lady Dunn looking quite as beautiful as when she married Sir James a decade before, Alice Worcester Howe the solid Yankee she had always been. In 1915 she had been startled by Howe’s abrupt proposal of marriage, thought it over for four months, and agreed. The date of their 1916 wedding had been determined by Howe’s priorities, a Saskatchewan provincial election and deadlines for grain elevator tenders, but Alice’s strong intelligence accepted them. Behind the garden gate, Alice Howe ruled her home, five children, and a monster Port Arthur furnace.

In 1953, the year of the coronation, Dunn invited Howe to become president of Algoma Steel, an offer repeated in vain in 1955. Dunn lived at St. Andrews in a large house that he called “Dayspring,” with a nine-foot wall around it; it was his main Canadian home. His work was at Algoma Steel in Sault Ste. Marie, but the company supplied two planes and four cars, and there was a small airport at Pennfield Ridge, thirty kilometres away from St. Andrews. Thus St. Andrews and the Soo came within commuting distance. Sir James died of thrombosis at “Dayspring” in January 1956, but Lady Dunn continued to live there. Howe had become part of the St. Andrews summer community, joining the rich regulars in the back room at Cockburn’s drugstore to gossip over the morning papers before a round of golf.

To this world Howe retreated, vast space looming in front of him. He confessed to Lady Dunn that he’d suffered a terrible blow, that he was now nothing more than a discarded politician, a gentleman of unwanted and unwonted leisure. Lady Dunn was a very rich widow, now fifty-seven years old. The death of her husband had been devastating to her; Lord Beaverbrook said she had wanted to go to a convent. He commented that she would have disliked the food and she “would certainly quarrel with the Mother Superior.” Her Greek ancestry showed in her quick temper and readiness to speak her mind. She was no fool at business either, and willing to take gambles. She was well aware that she could use Howe’s tremendous grip of finance and of the way things were done. She needed him. It is also fair to say that in some ways Howe needed her. No one had asked him to do anything; a company or financial institution that might have thought of him weighed up the 1956 pipeline debate and the obloquy he had acquired. Howe had been dropped out of his old world suddenly and completely.[1]

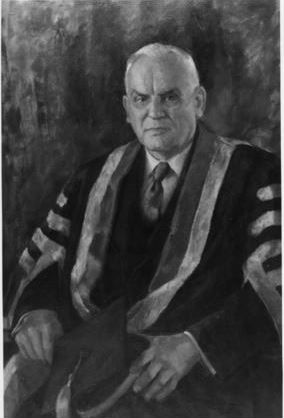

Howe Becomes Dalhousie’s First Chancellor

Without much apparent warning, on 8 August 1957, Dalhousie University invited Howe to join its Board of Governors. It was the first such invitation he had received since his defeat and he was thrilled with it, and with what followed. A week later, as the result of discussions at St. Andrews between Lady Dunn and President Kerr, the executive committee of the board agreed to create for Howe the office of chancellor. Howe was to be invited to assume the office “forthwith.” On 29 August the full board unanimously ratified this new departure. Howe was more than willing, not only from his circumstances in August 1957, but also because he owed much to Dalhousie and its men of 1908-12, “for my introduction to Canadian life,” as he put it to Archie MacMechan’s widow in Chester. “Perhaps I will now be able to pay a part of the debt that I owe to Dalhousie.”

Who prompted Dalhousie to act in this matter is not certain; Darrell Laing, chairman of the board, had never met Howe, but Howe’s name turns up as early as 28 June 1957 in correspondence between Laing and President Kerr. It is possible that Lady Dunn suggested Howe. It is certain that once Dalhousie had resolved upon Howe for its Board of Governors, she wanted him made chancellor. Howe thanked her; he said that his appointment was

due wholly to your intervention… I do believe that, between us, we can do much to make Dalhousie outstanding among Canadian universities. Fortunately, Dalhousie has a surprisingly high standing throughout Canada and many former students will be happy to see new life being injected into their Alma Mater. I hope that our discussions with Dr. Kerr and Brigadier Haldenby will be productive.[2]

For C.D. Howe and Lady Dunn talked about more than Howe’s becoming chancellor. He had said to her: “You should do something for Dalhousie yourself. After all your husband wanted to. Why not build the Physics building?” Thus the St. Andrews discussions were also about buildings and Lady Dunn’s role in funding them. The two official priorities of the board were, first, a men’s residence, for which federal money was available; and second, a new science building for Physics, Engineering, and Geology. To Lady Dunn, a men’s residence had little appeal; unlike Jennie Shirreff, who delighted in the prospect of imbuing young women with ideas of gracious living, Lady Dunn wanted a memorial to her husband more substantially academic. A new Law building was not yet in the cards; Law had moved into its new/old building on the Studley campus just four years before. Lady Dunn’s and Howe’s priority was Science and she offered substantial money, the whole cost of the building in fact. The public announcement was made within forty-eight hours of Howe’s acceptance of the offer of chancellor.

Thus Howe, Lady Dunn, and the Physics building – now to be called the Sir James Dunn Science Building – all came to Dalhousie at the same time. The science building would cost $1,750,000. The architects were to be Mathers and Haldenby of Toronto, neither Howe’s choice nor Lady Dunn’s. They had done the Arts and Administration Building, and although it had proved lamentably leaky, a report in 1956 on its defects attributed this to the contractors rather than the architects. Early in 1957, before Lady Dunn had invested the scene with her ideas and presence, Mathers and Haldenby had prepared a model of the campus showing old buildings and proposed new ones; it was not unreasonable that Dalhousie should turn to the same firm. Dalhousie’s priorities were now, however, abruptly reversed, in line with Lady Dunn’s, though planning on both buildings would be started at once.[3]

Creating the Sir James Dunn Science Building

Lady Dunn, Howe, and the board came to the official sod-turning ceremony for the Dunn building on Sir James’s birthday, 19 October 1957. That was fast work! Lady Dunn intended to have her memorial to her husband built and running as soon as possible, consistent, that is, with her demands for quality in materials and in construction. There was to be nothing slipshod in anything. She drove the enterprise and all connected with it hard – architects, engineers, contractors, university officials, and C.D. Howe. It was all they could do to keep up with her. She claimed her aggressiveness was apt to show when she was trying to shake off “an overwhelming depression.” If so, Howe endeavoured to combat it, especially relating to her finances. The steep succession duties made her feel she was gobbling up her capital too rapidly. Then there was her income; Howe patiently explained that the Sir James Dunn Foundation, being a charitable trust, had to spend 90 per cent of its income on charity each year. For now, the bulk of that would be going to Dalhousie for the Sir James Dunn Science Building. He assured her she was doing well financially and would do better. She had sold her Algoma Steel shares at what would be for a long time the top of the market, and her future problems would come not from having too little income but from too much. At Dalhousie, Howe said, she was already thought of as the “Guardian Angel” of the university, and she would derive great satisfaction from her association with it.[4]

But despite Howe, it was not smooth going. It became a parallelogram of forces: Lady Dunn (and her Montreal lawyer W.H. Howard), President Kerr, Mathers and Haldenby, J.H.L. Johnstone of Dalhousie Physics Department, with Howe trying to keep it all in strained balance. Mercifully for Dalhousie, Howe was neither by inclination nor talent just a figurehead; his energy and experience he applied vigorously to Dalhousie’s problems.

Lord Beaverbrook took notice of what was going on between Dalhousie and the widow of Jimmy Dunn, his old friend. He was always on the look-out for the chance to improve the interests of the University of New Brunswick; he had been its chancellor since 1947, and life chancellor since 1954. In September 1957 he invited Howe to Fredericton, showed him proudly around his university. Nor was Beaverbrook without designs on redirecting Lady Dunn’s interest from Dalhousie to UNB; he was constantly sending her what she called “interesting” letters. And she was not the only rich widow Beaverbrook was looking to. He and Mrs. Dorothy Killam both wintered regularly in Nassau. One night Beaverbrook arranged for a number of male guests to dine, telling them ahead of time that the object was to get some of Dorothy Killam’s money for UNB. She would be the only woman there and she would like that. The men were as charming as possible; Dorothy Killam was likewise, aided by her consummate knowledge of men and finance. It was a delightful evening, but Mrs. Killam left without giving anyone anything other than thanks to her host. Beaverbrook said afterward, “She beat us all.” Howe met Mrs. Killam in New York in September 1957 about the use of monies that her husband had given Dalhousie years before under the rubric of “Anonymous Donor.” Howe knew enough about the ways of the very rich not to push his luck until time and occasion offered. For if Dorothy Killam could say no with grace, as with Beaverbrook’s crowd, she could also be cuttingly abrupt.[5]

Howe himself, that autumn of 1957, was being solicited to join boards. Far from dropping out of public life, his view in August and September, by December he had been accepting a directorship every three weeks: National Trust, Atlas Steels, Federal Grain, Bank of Montreal, Domtar (an E.P. Taylor paper company), to say nothing of the board of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he had graduated fifty years before.

In the meantime Dalhousie collected ideas about what chancellors actually did, from McGill, Toronto, and Western. The duties were laid down in board minutes in December 1957. The chancellor was elected by the board for a term of five years. If present, he or she presided at convocation. The chancellor was a member of the board but not the chairman. In effect, the office was what the chancellor chose to do with it. Frank Covert likened it to the role of the crown in Parliament. He was delighted with Howe’s appointment, “probably the most outstanding man in Canada today,” and wanted him kept au fait with Dalhousie business from month to month, for he “grasps things quickly and has an extraordinary talent for overcoming difficulties in the quickest, simplest and most effective manner.” The appointment of a chancellor did require changing the Dalhousie Act of 1863, which was now to be thoroughly revised and brought up to date. Opening up the act was not too risky, as Robert Stanfield (’36), premier since 1956, was well disposed to Dalhousie. The revision was actually done in the spring session of 1958.[6]

None of Howe’s new interests got in the way of his primary occupation: building up Dalhousie University. It was just as well, for Lady Dunn’s relations with Dalhousie officials and the architects required constant attention. Brigadier Laing wrote her in November 1957 with the sensible suggestion that Dalhousie would save money by tendering for both the Sir James Dunn Building and the men’s residence at the same time. She was indignant. Mathers and Haldenby should not have their attention thus diverted. “Now Clarence dear,” she wrote Howe, “do not be vexed but I wrote a sharp retort to Brigadier Laing.” The residence could be dealt with by local architects in Halifax, but let Mathers and Haldenby concentrate upon her building. “I do not want a POOLED JOB I want a PRIORITY JOB.” She suspected Laing and the Dalhousie board of trying to wheedle money – Dalhousie needed a further quarter-million for the men’s residence – and that pooling tenders for the two buildings might be one way of disguising it. Howe reassured her. There would be no double tendering. Laing was, Howe said, a first-class man and had no ulterior motive. Howe would himself keep a close watch on the Dunn building, go over the tenders himself, a business in which, he said, “I have had a good deal of experience… If we do not get a first-class job I will admit that I know nothing about the construction business.” Lady Dunn was mollified, but noted, shrewdly enough, “as you see, things wander around a bit unless the reins are tightly held – I am so glad you have all the reins in hand now.”[7]

At this point President Kerr interposed a completely new suggestion: would Lady Dunn like to broaden her support by establishing a chair in divinity? Howe wasn’t having it. A most unwise move, he said, not only because it distracted her, but it threatened to disturb the hitherto harmonious relations between Dalhousie and Pine Hill Divinity School. At New Year’s 1958 Kerr suggested that Dalhousie should use Lady Dunn’s support to found a chair in Gaelic. Howe was cool to that suggestion too: “My advice is that we move slowly in widening the range of education at Dalhousie. The expansion in science will require two or three new professorships, and no doubt reinforcement of your existing staff is required in other directions.” Clearly he was developing a dislike of Dalhousie’s president.

Howe was officially installed as chancellor on 29 March 1958. By some egregious error on Dalhousie’s part, Lady Dunn was not invited. She was angry as much at the “casual impromptu flavour [of the ceremony] which I deplore” as at not being invited. She soon learned that after the ceremony Dalhousie gave only a buffet lunch and in the basement of the Arts Building at that. The drink was water. Think of it! she wrote Howe. When Beaverbrook installed himself (as she put it) as the chancellor of UNB there was “one week of revelry and merriment, with BANQUETS & BALLS… I find it hard to take that this truly HISTORICAL OCCASION should be given only a Buffet Luncheon with water.”[8]

That was not the end of Lady Dunn’s unhappiness. In mid-April 1958, when the contract had been awarded for the basement and foundations of the Dunn building, out of the blue the architects’ estimate of the total cost rose suddenly by $350,000, (that is, 20 per cent) to $2.1 million. This time Howe was indignant; there should have been some warning of a change of such magnitude. “Why Dalhousie wished to use a Toronto architect,” he grumbled, “is beyond me.” The 20 per cent hoist only came to light because W.H. Howard, Lady Dunn’s Montreal lawyer, required specifics before the 1 May payment from the Dunn Foundation was made. Lady Dunn was anything but pleased. She paid up, protesting to Howe that this new figure was going to be the absolute limit. It was.[9]

In May 1958 Howe presided at Dalhousie convocation and the graduation ball at the Nova Scotian Hotel where, he added, there was no alcohol but the students enjoyed themselves anyway. He found convocation tedious and the tea party afterwards at Shirreff Hall no compensation. Lady Dunn was already planning a big party and ball for the students on 29 October, when the cornerstone of the Dunn building was to be laid, and was prepared to do it in style. President Kerr was adamant that there be no beer, wine, or any form of alcohol. Lord Beaverbrook told Lady Dunn that at such a function to do without beer or wine would be “bloody.” Better not have a party at all! She echoed Beaverbrook’s sentiments. She had been looking forward, she told Howe, to “a gay, gladsome, gala affair and NOT just an ordinary HOP with POP.” She wrote Kerr severely that “one could not celebrate a Birthday (especially this one) in tap water.” She would await his views. Kerr still insisted that it was contrary to university regulations. Lady Dunn could, if she wished, give a birthday ball privately. “In my thirteen years at Dalhousie we have never served liquor of any kind at university functions, and I hope it will continue that way.” It was left to the chairman of the board and Howe to sort out.[10]

The next shock – in mid-August 1958 – was the postponement of the official completion of the building from 1959 to 1960. That too was treated casually and without explanation. Lady Dunn and her lawyer were grievously annoyed. Why was she not told and some reasons given? Off went a blistering letter from W.H. Howard to Brigadier Laing; Dalhousie’s treatment of Lady Dunn was quite inexcusable. And, the lawyer added in a sinister turn of phrase, “It may well prove to be most unwise.” Laing did not like receiving such missives, not from lawyers, not from anyone. He suggested with some terseness that Howard control his language or his letters would not be answered at all. Howe tackled Haldenby in Toronto, accusing the architects of neglecting supervision of the Halifax work, in particular the expediting and management of materials. This effected some shaking up there and in Halifax. William Wickwire was made chairman of the board’s Building Committee, and Howe got Professor J.H.L. Johnstone of Physics to act as Wickwire’s deputy.

Johnstone and Howe were on first-name terms. They had known each other since Howe’s days at Dalhousie; Johnstone had graduated in 1912, Howe’s last year as professor of engineering. A specific example of their cooperation occurred in early October 1958 when a major hold-up occurred in getting cut sandstone from Phillipsburg, Quebec. The contractors seemed powerless; Johnstone phoned Howe. Howe leaned on the quarry management; the stone was shipped by truck and was in Halifax in five days. Johnstone also was hard on the contractors. At the beginning Howe and Johnstone had to read them the riot act more than once; Johnstone’s refusal to let defective material get by was unpopular with them, but as Howe put it later, it was “very popular with me.”[11]

On 29 October 1958, the day of laying the cornerstone, the university declared a half-holiday. At a special convocation Beaverbrook gave the principal speech, about his old friend Sir James Dunn. By this time Lady Dunn had backed away from giving a party, reserving that for the completion and opening of the building. Instead, Howe gave a dinner at the Nova Scotian for 150 guests and a ball for the graduating students in Arts and Science, Law, and Engineering. He would demonstrate that Halifax could do things in style! Beer, wine, and liquor were to be served at both, in the teeth of Kerr’s resistance. It came up at the board meeting just before Howe’s party. The president said he assumed no drinks would be served, as this was not the Dalhousie custom. Howe smiled and said nothing. Towards the end of the meeting he repeated his invitation, saying that he would see everyone at the Nova Scotian at 7:00 PM that evening. Kerr spoke again; he would wish to remind the new chancellor about the Dalhousie restriction on alcohol. At this Howe bridled. “See heah Doctah Kahr,” said he with his flattened Massachusetts “r”s, “this is my pahty, not yours. Just remember that and if I plan to have wine served, wine will be served. You don’t have to come if you don’t want to.” Thus had Howe and Laing solved the impasse between the president and Lady Dunn.[12]

Brigadier Laing, tough, exigent, able, was one of Dalhousie’s most effective board chairmen. But on 1 September 1958, at the age of fifty-nine he died suddenly of a heart attack. Howe took on the task of finding a new chairman of the board. He tried to persuade his former cabinet colleague J.L. Ilsley, the chief justice of Nova Scotia since 1950, to take it, but failed. The next best prospect was Donald McInnes (BA ’24, LL.B. ’26), whose father, Hector McInnes, had served on the Dalhousie board for over forty years. McInnes accepted. William N. Wickwire was named vice-chairman. They were both busy Halifax lawyers, and the danger existed that neither would spend enough time at Dalhousie affairs; both together, Howe reasoned, might get results. It was just as well, Howe told Lady Dunn, for “there is a job to be done that cannot be too long delayed.”

Strengthening the Law School

That job in November 1958 was strengthening Dalhousie’s staff with new appointments, better salaries, an end to the quasi-starved condition that had prevailed under Kerr’s aegis through the 1950s. The Law School was one of the first of these concerns. In 1957 changes initiated by Osgoode Hall made Dalhousie Law School graduates more exportable than ever before. The Dalhousie LL.B. had won partial outside recognition in 1952, and complete, in all the Canadian common-law provinces, in 1957. Thus an Ontario student wanting to practise in Ontario no longer had to go to an Ontario law school. For the Dalhousie Law School which had always, as its historian John Willis put it, to export or die, it was a considerable step forward, and the first of three substantial changes in 1957.

The second was raising the standard for Law School admission. Dean MacRae in 1921 (effective in 1924) raised the requirement to two years of arts, and persuaded the Canadian Bar Association that it should be the standard in all the Canadian common-law provinces. Dalhousie had in effect imposed a new national standard. In 1957 a three-year arts prerequisite became the national rule, and perforce adopted by Dalhousie; this time a Canadian rule was imposed on Dalhousie.

A third 1957 innovation was the arrival of G.V.V. Nicholls, who had been editor of the Canadian Bar Review for ten years, trained in civil law in Quebec and France. Nicholls had a formidable mind; experienced, tough, he was ready to question traditional Law School ways of doing things. He established a compulsory first-year course in legal research and writing, which required every student to present in writing a reasoned solution to a legal problem. As a method of training law students it was far more effective than the prevalent case method, in which the student had to do no more than to take part – or not – in class discussion. Prior to Nicholls’s course, some students had never submitted anything to anyone until they wrote examinations. Nicholls gave supervision on an individual basis and hard work it was for him and his students.

Nicholls’s course in turn compelled a long overdue development of the law library. Nicholls was shocked by it: no catalogue, no full-time librarian. The runs of old law reports probably sufficed for case method courses, but were wholly inadequate for legal research and writing. Dean Read, armed with a savage report from Nicholls, now sought a full-time librarian. But he had little money and no success until Lady Dunn came to the rescue.[13]

Her interest was aroused by a letter from W.R. Lederman, the Sir James Dunn professor of law, a chair established by Sir James in 1950. Lederman had found it impossible to resist the invitation of Queen’s to become the founding dean of its new law school, but he felt it his duty in July 1958 to acquaint Lady Dunn with his concerns at Dalhousie:

In the field of legal education, the most striking advances in Canada’s history are now rather suddenly developing in other places. This means that exceptional and sustained efforts are necessary if Dalhousie Law School is to hold the position it has always had in the very front rank of Canadian law faculties. I fear that the urgency of this situation is not at present appreciated, except among the members of the Dalhousie Law Faculty itself.

When he pointed out that the Law School was not being given its fair share of the university’s resources, Lady Dunn took it up at once, and made sure that Howe knew. “Please tell me,” said she to Lederman in effect, “the wisest course to follow.” Lederman replied that four things needed attention: salary levels, more staff, a well-qualified law librarian and money for books, and scholarships for good students. Howe arranged to see Dean Read. Within three months in October 1958, answers to Lederman’s questions were announced at the symposium and convocation to celebrate the Law School’s seventy-fifth anniversary: Lady Dunn would give $16,500 a year to hire a good law librarian and assistants, with the proviso that Dalhousie would give $10,000 a year for books, and $10,500 a year to provide seven Sir James Dunn law scholarships at $1,500 a year each. The scholarships were unique; no other law school in Canada had anything like them.

Dean Read found working with Lady Dunn no easier than Jack Johnstone had. When he asked the foundation to help make public the scholarships, Lady Dunn bridled. An agent of the Law School! She thought the scholarships could and should stand on their own. Read then made the mistake of asking for advice on getting out an announcement. Lady Dunn wanted decision. It was, she thought, “a most discouraging beginning.” She did not even want to see Read. Howe got Read to draw up the pamphlet on the Dunn scholarships, which turned out to be exactly what Lady Dunn wanted.[14]

Howe hoped for much from Donald McInnes, the new chairman of the board. The first issue he seems to have tackled was raising Law School salaries, something Kerr had long resisted. McInnes locked horns with him in December on that and won. Lady Dunn was delighted, but told Howe that Dalhousie would need Howe’s continued pressure. The most serious problem was the salaries and conditions of the Faculty of Arts and Science.

Lady Dunn believed in first-class staff, a lesson she had absorbed from her husband’s experience with Algoma Steel. He had gone to Sault Ste. Marie knowing nothing about making steel but hired the best men he could get to make it. Lady Dunn took the position that it was money wasted to have a first-class Physics building without first-class professors to run it. Both she and Howe had been making this point with increasing insistence. From the faculty side it was Dean Archibald who brought it to a head, and he made sure his protests got past the president’s office to McInnes and Howe. His term was three years, and in September 1958 he handed in his resignation, telling the board the reason he did not want to continue was President Kerr’s complete disregard of his recommendations for the improvement of salaries, especially in science. Lady Dunn backed Archibald. She liked him personally, and thought Archibald’s own salary was well below what it should be. Indeed, she felt, all the Arts and Science professors were underpaid. After negotiations, Archibald agreed to carry on. A new salary scale brought in by the board, as of 1 September 1958 no doubt helped, but Archibald insisted that adjustment in a clutch of a dozen individual cases was necessary, indeed urgent, since they affected the best women and men in Arts and Science. To do otherwise was to risk losing them.[15]

Lady Dunn and Howe versus President Kerr

Other problems with Dr. Kerr annoyed Lady Dunn. When Dalhousie did not publish Beaverbrook’s tribute to Sir James Dunn at the laying of the cornerstone, she had it printed herself. She did not complain about paying the cost; what upset her was that Dalhousie had not thought of it. Apparently no one, except Howe, had any flair for handling such matters of state. Indeed, Beaverbrook’s speech would not have even been reported had not the Saint John Telegraph-Journal arranged for it. It was symptomatic of a whole range of issues from large to petty. The gifts to Dalhousie that ought to have given Lady Dunn pleasurable challenges had produced mainly irritating ones. She complained that with Kerr as president she had lost her enthusiasm. “I expected to be quite active and interested but I certainly have been disappointed, frustrated and irritated.” Probably few presidents could have avoided offending such a formidable lady, but Kerr did not help. Dalhousie’s gratitude offered her “an abundance of superficiality” but was “sadly lacking in tangible appreciation.” Kerr was unquestionably appreciative of all she had done; he did not know how to translate it either in letters or in action. His letters were prosy, flat, and unconvincing.[16]

Howe entirely understood. It shook him that Lady Dunn had to pay for the publication of Beaverbrook’s speech.

The whole trouble at Dalhousie is Dr. Kerr. He is a mean spirited man. Everyone agrees he should go, but no one seems to do anything about it. I hope I can stir things up while I am in Halifax…Bringing the standards of Dalhousie, both in business and in education, up to those of the Dalhousie of my day, is a real challenge, but I believe that it can be accomplished. I am going to do my best to that end. The Dalhousie tradition is worth restoring… There seems to have been a complete lack of leadership since Kerr became President. I still have hopes of Donald McInnes.

One task he had in hand was to join with Ray Milner, the chancellor of King’s, to promote better understanding between Dalhousie and King’s. Here again Kerr was the main obstacle, and his fighting “vigorously against any concession by Dalhousie… did not help.” Nevertheless a new Dalhousie-King’s convention was signed a few months later, in November 1959.[17]

According to Lady Dunn, Kerr was trying to carry two roles, that of a United Church minister and president of Dalhousie. She was perturbed that in a period of expansion Dalhousie should be saddled with a part-time president. “I do not intend to be meddlesome,” she told Howe, “but since I have had Dalhousie very much to the fore in future planning, I do intend to know – what now?” There were strong intimations that, while she disclaimed any intention of being presumptuous, she expected to be consulted before a new Dalhousie president was appointed. Howe agreed. “I have made it clear to all concerned that you must be consulted about all matters associated with the change in the Presidency.”[18] Among Howe’s grievances with Kerr, one was uppermost: he was not listening to his deans or sufficiently consulting his board. He was apt to make important decisions and commitments without consulting anyone, referring less important ones to the board. Howe had more confidence in the management of Dalhousie when Kerr was away than when he was there. Steadily he and McInnes worked to increase the authority of the deans. In any case, Howe confided to Lady Dunn, Dalhousie should get rid of its president as soon as possible. Howe pushed McInnes, reminding him that Kerr’s standing in the Canadian university world was small credit to Dalhousie, that as long as Kerr was there it would be difficult to attract men of high calibre to the staff or keep good professors. But McInnes was made of rather soft metal, and getting rid of an incumbent president who had no intention of going was difficult. McInnes disliked contretemps; if President Kerr would not resign on his own, McInnes was not yet ready to force him. And there was another reason: Dalhousie had fired its president in 1945, only fourteen years before, and its board now had a natural reluctance to fire another one. Thus while Howe could talk, suggest, even lead at times, he had only one vote on the board the same as the others, and he did not always get his way. Indeed, “some of the Board regarded him as an interfering bustle from Ottawa not a real Nova Scotian.”

Howe explained it all to A.T. Stewart, professor of physics, who was leaving Dalhousie in September 1960 to go to the University of North Carolina, mostly because of Kerr. Howe had tried to persuade the board to buy Kerr off, but they wouldn’t move. Changing the president of a university, Howe confessed to Lady Dunn, was “almost as difficult as changing the leader of a political party.” Howe did solicit nominations for a new Dalhousie president in September 1960, from his old friend Larry MacKenzie of UBC, but until President Kerr actually intimated resignation it was bootless to go further.

Howe told Kerr that Dalhousie’s obsession with buildings had allowed its staff to deteriorate. The building program had been extravagant and Dalhousie salaries showed much evidence of penny pinching. Fifty years ago, Howe reminded the alumni, Dalhousie was one of the four great English-speaking universities in Canada even though it had only one building. Not only that, but fifty years ago, too, Howe’s salary as a young professor of engineering, $2,000, was a great deal more than the $5,000 that Dalhousie professors of similar age were earning currently.[19]

These were the shadows in the background when the Sir James Dunn Science building was finally opened in October 1960 with considerable fanfare, Howe giving another splendid dinner party at the Nova Scotian, flaunting the occasion to show Lord Beaverbrook what he and Dalhousie could do. As he told President Kerr,

I was annoyed at the invasion from New Brunswick, and also fed up with reports from Fredericton on the wonderful dinners given by Lord Beaverbrook on a similar occasions. My purpose was to show New Brunswick that we in Nova Scotia could also arrange a dinner. I think that Beaverbrook got the point. I was not in the least perturbed about the cost.

Lady Dunn was finally thrilled both with the building and the way it was celebrated. The weather of late October was perfect.

By this time, however, Lady Dunn’s frustrations with Dalhousie during the three-year process from sod-turning to opening had turned her towards Beaverbrook. In 1959 she asked him to write a life of Sir James Dunn; he asked for and got her help and the papers she had. She spent some weeks early in 1960 at Beaverbrook’s place, La Capponcina, in the Riviera, and her correspondence with Howe gradually dried up. Howe warned McInnes that Beaverbrook was making a tremendous play for Lady Dunn, that they were spending most of their time together. Ostensibly this was because of the biography of Sir James; but Beaverbrook had a darker purpose, to redirect Lady Dunn’s money from Dalhousie to UNB. Howe cautioned her with shrewd advice: whatever money she gave Dalhousie would glorify her husband; anything she might give UNB would simply glorify Beaverbrook. She paid attention to that. Still, it did not prevent her from marrying Beaverbrook in June 1963. He died a year later, having failed to divert any of his new wife’s money to UNB although she did build the Sir James Dunn Playhouse in downtown Fredericton.[20]

She left a considerable legacy at Dalhousie. No one had ever given it so much money nor created more problems in its giving. She was a strange figure, descending upon Halifax out of St. Andrews; some suggested aerial conveyance other than aeroplanes. She worked her will with outrageous ruthlessness. Her poetic effusion about her husband she required every Dalhousie graduate student to sign for. Remembrance was as risible in content as in process, studded like her letters with block capitals, radiating her delight in her husband. Her memory of him also included his lessons, that “IGNORANCE was a calamity,” that “there is no substitute for CONCENTRATION – it is a MAGIC FORMULA.” After this sermon there followed an eight-page poem, “The Ballad of a Bathurst Boy, 1874-1956,” perilously close to doggerel most of the time, in it at others:

His fighting heart had won for him

A ten dollar boxing prize –

Intrigued by “Memory Lectures”

Proclaimed by posters of great size.

(Sir James had spent his $10 prize going to a lecture on “assimilative Memory.”) But she left an imposing building, and splendid Sir James Dunn scholarships in law. She had strong views of what Dalhousie ought to be, and she wanted it soon. It was not an easy prescription for a university with fractured and complex governance to translate into action. It was C.D. Howe who was the main Dalhousie stand-by and through whom her demands and complaints were channelled. She had one aim: to make the Sir James Dunn Building as handsome as possible within the money, $2,175,000, and the time various exigencies had forced her to accept. She aimed high and kept Dalhousie’s best interests to the forefront; but she was quick to take offence and often got her exercise jumping to conclusions. She wanted everything just right, and if it wasn’t right she wanted it done again. She did not want the tops of the elevator shafts protruding from the top of the building; a $250,000 parapet was put on to conceal them. She did not like the marble in the lobby; it was replaced. The door handles were all wrong; they were changed. The details were interminable. And through it all ran her fear of, as she put it, “being soaked” unless she were vigilant, or as it turned out, she persuaded Howe to be.

Howe found her difficult. Very early he complained to the architects that he and they were “victims of too many bosses, including especially Lady Dunn and Dr. Kerr.” But as Howe put it two years later, with some exaggeration, “Lady Dunn’s benefactions… constitute the most exciting development in the history of Dalhousie. It has put new life into the university, and is attracting interest, both from students and potential staff.” Jack Johnstone, upon whom rested much of the local supervision for the Dunn building, was in hospital in September 1960 as the building was completed, his work much appreciated by Howe “in keeping everything first class.” That Dalhousie was able to close accounts on the Dunn building with a $27,000 credit balance was, said Howe, due largely to Johnstone. As for Johnstone himself, by 1959 he had had all he could stand of Lady Dunn. At one point a colleague asked him jocularly, how much would he kiss someone’s a… for? Johnstone replied with a rueful grin, “I can tell you that exactly: $2.1 million.”[21]

Dorothy Johnston Killam, LL.D.

Howe also had in mind the care and cultivation of Mrs. Dorothy Killam, an exquisitely sensitive operation. Beaverbrook had failed. So also had Ralph Pickard Bell, who chaired Mount Allison’s fundraising committee in 1959 and became chancellor in 1960. On hearing that the Reverend W.S. Godfrey, a well-known Mount Allison alumnus, was going to the Bahamas to see Mrs. Killam, Ralph Bell told him to back off, that he would go. Bell, not famous for subtlety, got nowhere and angered Mrs. Killam. “He told me how to spend my money!” “There was,” said her lawyer, Donald Byers, “a certain delicacy required.” Watson Kirkconnell, president of Acadia University from 1948 to 1964, knowing Mrs. Killam was fond of baseball, especially of the Brooklyn Dodgers, spent hours studying both before going to the Bahamas. “Oh, yes,” he said, “and it didn’t do Acadia or me one darn bit of good.” Dalhousie’s credentials were better, however. Isaac Walton Killam was a Dalhousie graduate, and his Halifax lawyer had been J. McG. Stewart. The “Anonymous Donor Fund” was started by Killam, and Howe was hoping to get another half-million to add to the $50,000 already there. If so, Howe noted, it would be the first gift Dorothy Killam had made since Killam’s death in August 1955. but she told Howe at that point that she proposed to give no money except in her will.[22]

That did not prevent Dalhousie from offering her an honorary degree in 1958; she could not accept it then, but when the offer was renewed in the spring of 1959, she did. Howe told Kerr that Mrs. Killam was unpredictable, that even if she accepted it did not mean that she would come. Mrs. Killam’s possible arrival in Halifax posed awkward questions. She very much liked centre stage, and her entourage would be certain to make a considerable splash. Lady Dunn was well capable of being jealous; she had been offered the degree and had declined it because the Dunn building was to commemorate her husband, not herself. Nevertheless, she would not enjoy seeing Mrs. Killam getting one. What seems to have happened – it is an hypothesis – was that Howe persuaded Mrs. Killam not to come, that the accommodation she wanted at the Nova Scotian Hotel was not available, and that no amount of pressure from McInnes and himself could change that. Why not, he said, plead illness, and he would undertake to persuade the Dalhousie Senate to give Mrs. Killam her degree in absentia in spite of tradition to the contrary. C.L. Bennet, the vice-president, was sure that Senate would accept this breach of its rules, if some responsible person would assure Senate of Mrs. Killam’s inability to be present. Senate did so accept. Thus did Mrs. Killam get her Dalhousie LL.D.; thus did Howe manage to keep Dalhousie’s two queen bees separated.[23]

In due course Mrs. Killam’s lawyer authorized the use of the $50,000 for the improvement of Dalhousie salaries. No part of it, said he sternly, was “to be used for capital expenditure.” In December 1959 Dalhousie received $100,000 as a tangible expression of Mrs. Killam’s ongoing interest, and no doubt gratitude for the honorary degree. Howe told McInnes not to tell Kerr or anyone else about the latest gift, that when the cheque arrived to let him (Howe) know, and he would send a proper letter of thanks. Another $100,000 came a year later. Mrs. Killam assured Howe on 19 December 1960 that handsome provision for Dalhousie was being set out in her will.[24]

Howe seems to have urged the appointment of Frank Covert as chairman of the board’s new committee on the pension fund. The pension initiative had come from Senate, raised in a joint meeting with the board in April 1959. The whole question of Dalhousie pensions badly needed further study, and a joint committee was struck chaired by the ablest financial expert on the board, Frank Covert (BA ’27, LL.B. ’29). He was fifty-two years old, and RCAF veteran with Distinguished Flying Cross, a friend of Howe’s from late in the war when he worked for the Ministry of Munitions and Supply. Now a director of the Royal Bank, Montreal Trust, National Sea Products, and on the Dalhousie board since 1955, Covert had energy and determination. A comprehensive report on Dalhousie’s existing scheme prepared by J.S.M. Wason showed its inadequacy, and a new plan was developed, to go into place on 1 January 1960 (later backdated to 1 September 1959) replacing the antediluvian one based upon Dominion annuities. The most ingenious aspect of the new Dalhousie pension was the decision to take up a trusteed plan rather than an insured one. This meant that Dalhousie would now administer its own pension fund on terms it itself decided on. Much depended on judicious, systematic, progressive administration of the fund. That, it is proper to say, is what it got.[25]

Covert wanted restrictions on the portability of the new Dalhousie pension. The Canadian Association of University Teachers had been urging portability upon Canadian university presidents. So had Dean W.J. Waines, of the University of Manitoba. Covert had worked with Waines on the Royal Commission on Transportation; “a nice fellow,” Covert said, “but ‘all sail and no rudder.’” For a small university, portability of pensions was impossible, but big universities such as British Columbia, Manitoba, and Toronto liked it. As soon as a better offer came, the professor at the small university left, taking his whole pension with him. It “makes me boil,” Covert said, “when people slavishly say somebody recommends it, someone does it, and therefore we ought to, and I think I have made it clear, insofar as Dalhousie is concerned, that we should have nothing to do with portable pensions.” If a professor wished to move he could take with him his own pension contributions, but Dalhousie’s contributions only on a sliding scale: after eight years’ continual service, one received 8 per cent of the board’s contributions, which increased at 8 per cent per annum until, after twenty-one years’ service, full portability was achieved. That, of course, was the best part of a working lifetime. Still, the new 1959 pension plan was a vast improvement on what had gone before.

The problem remained of older professors, with substantial years under the old plan, but with few additional benefits from the new one. Some professors who retired in the 1960s found the financial going difficult. A few could not even afford to live in Halifax any longer, but migrated to the countryside around, or to a less expensive university town such as Wolfville. Covert had some sympathy for such professors; when G.V. Douglas complained in 1957 that his pension was only $1,721 a year, the board supplemented it with $700. But Covert reminded President Kerr of an old perspective: the great majority of people still did not get pensions from their place of work. Covert noted that Douglas, as full professor from 1932 to 1957, had a salary far higher than anything Covert got as a lawyer until well after the war, and Covert said he had to work harder for what he got. Furthermore, he had to fund his own pension. In those days, before the Canada Pension Plan of 1966, people had to save and plan for their retirement. That was Beecher Weld’s rejoinder to griping by retired colleagues. Still, a modest pension in a time of steadily rising prices too often produced income woefully inadequate.[26]

Dalhousie’s endowment was entirely separate from its pension funds. It, too, needed systematic and hard-headed administration. Dalhousie’s endowments, Howe suggested to D.H. McNeill, the business manager, were scattered to such an extent that it was impossible to watch them all. Now would be a good time to consolidate. Furthermore, Dalhousie “should not be operating with a substantial surplus at a time when faculty salaries are substandard.” Any appeal for funds could hardly go forward on the basis of Dalhousie’s financial position. It ought not to be having surpluses. Two years later Frank Covert, now chairman of the board’s Finance Committee, was asked to prepare a report on Dalhousie investments. The result was a stern indictment of the work of the Finance Committee. Covert criticized too slack control, too many easy-going investments such as municipal bonds, and not enough concentration on growth stocks. “We as the Finance Committee,” he told McInnes, “have done a poor job.” He also called for new blood; Dalhousie’s endowment was now too big, with a market value of $14.5 million, “to leave it in the hands of amateurs.”[27]

One of the last changes Howe presided over was the appointment of a new dean of arts and science. Archibald had agreed to stay on in 1958 on condition that there would be some improvement of staff salaries, a subject on which Kerr gave ground unwillingly but which Howe and Lady Dunn fully approved. By 1960 Archibald was finding it impossible to work with the president. There were numerous examples. Archibald badly wanted to keep Professor Peter Michelsen in German. Kerr dragged his feet, and when he was finally badgered into making a decent offer, Michelsen had accepted a post in Braunschweig. D.J. Heasman of Political Science was invited to the University of Saskatchewan for a year as visiting professor. Archibald had the sensible view that this was good for Heasman and good for Dalhousie, and told Aitchison, the head of the department, that it was an excellent idea. Kerr was not pleased. Archibald should have discussed the whole matter with him first. Crowning it all in the summer of 1960 was Kerr’s meanness over J.H.L. Johnstone’s salary. Johnstone had done tremendous work for the Dunn building, and almost died from a duodenal ulcer that summer. He would return to work that autumn and he thought a salary of $10,200 would be fair. Archibald thought so too. Kerr accepted the salary minus Johnstone’s annuity entitlement of $1,620. It took another round of negotiations before Johnstone’s salary was finally established at $10,000 without any deductions.[28]

As those disagreements suggested, the president was at the core of the decision-making in Arts and Science, and he proposed to stay there. It was by far his most immediate interest. But his ideas were increasingly out of tune with faculty’s. Dean Archibald spent hours trying to hold off Kerr’s pressure for new programs such as secretarial science or home economics, that aimed at accessibility at the expense of Dalhousie standards. Archibald needed a faculty council to help him “keep Kerr on the rails,” as he put it. In a stern letter addressed to Kerr, C.D. Howe, and McInnes in April 1960, Archibald insisted that dean and faculty be given freedom of decision about appointments and salaries within an approved budget. Three days later, the faculty passed without a dissenting voice a bluntly worded resolution:

The Faculty is now in the precarious state reached by the Medical School six years ago when Dr. C.B. Stewart wrote of it… “only a strong and concerted effort… can bring it to safety, let alone to the position of eminence that it should occupy.” As the situation now is, members of the Faculty cannot convince, or even honestly advise, desirable staff members that they should come to Dalhousie… it is essential that the Faculty be given the degree of autonomy and machinery of administration and consultation possessed by the Medical School.

Kerr said he was in agreement, though he may not have had much choice. A faculty council of eight members was struck within a week.[29]

Resignations were the most obvious evidence of disaffection. In the summer of 1960 D.G. Lochhead, the university librarian, left for York University, the new university in Toronto, after seven years of fighting Kerr. He said that Kerr did not like libraries or librarians, so niggardly had been his treatment of them. Lochhead concluded that the board had been tight-fisted because its chief executive officer was. A.T. Stewart of Physics was amazed not only that his $100 travel voucher had to be signed by the president, but that the president would give him a lecture on how George Grant’s departure would benefit Dalhousie.

George Grant left Dalhousie in 1960 for the same reasons, and like Lochhead for York. Kerr had once liked and approved of Grant but now found his philosophical and theological opinions too unsettling. King’s used to require their divinity students to take Grant’s Philosophy 1, but now discontinued the practice. Grant raised doubts about their faith, President Puxley said, giving them nothing in return but scepticism. Roman Catholic students were cautioned against attending Grant’s lectures. Grant resigned in December 1959, effective the following August, but he was out of his York job when he left Halifax in August 1960, having quarrelled with President Murray Ross over the terms of his York appointment. Grant might have been persuaded to stay; Kerr would not have it.[30]

Thus it was not surprising that in the fall of 1960 the Gazette under Denis Stairs, editor-in-chief asked, “Why Did the Professors Go?” He suspected friction between professors and president, but suspicions were not reasons. He waited. When there was no answer the following week, he noted the fact. By that time the Gazette had been encouraged privately with information from good sources: Professors J.G. Kaplan, of the Department of Physiology, of the Dalhousie Faculty Association, and Allan Bevan, head of English. Most interesting of all, Stairs was urged to press on by a board member who complained that between the executive committee and the president, ordinary members of the board were kept in the dark and had little idea of what was going on. A week later, “Why Did the Professors Go?” was in still bigger type, the Gazette saying that Dalhousie’s “teaching and research conditions are stifling.” On 27 October “WHY DID THE PROFESSORS GO?” took the whole top of the page. The Gazette suggested that the conditions in Arts and Science resembled those that produced the 1954 Medical revolt. It urged the new Faculty Council of Arts and Science to take up the torch. The Dental Faculty was, however, angry at the Gazette; the big headline came during an important dental conference in Halifax. J.D. McLean, dean of dentistry, wrote the president:

The impropriety of this exceedingly ill-timed editorial, however, has caused great alarm. Regardless of any semblance of fact that it may contain, the advertisement to our distinguished guests of this week from so many parts of the world, could do our university untold harm which may take years to correct.

In Senate there was talk of the editor’s suspension, choked off by the sensible argument that it would be counter-productive. The editor, Denis Stairs, in his final year in honours history, was then approached by one of his professors who said the Gazette had made its point, and the president could not properly reply owing to the confidentiality of his information. Still, the fact that the president said nothing at all suggests that he simply did not deign to answer. The following week, the Gazette shut itself up on the subject, its case already made.

All that autumn of 1960, C.D. Howe had been busy. One day in Halifax, Gordon Archibald of the board was driving him to the airport bus, mentioning that he worked for the Heart Fund. Howe, jocular, said, “Well, heart disease solves a lot of problems.” During one three-day period in mid-December Howe attended meetings, in New York, Welland, and Quebec City. His acquaintances noted his exhaustion. At Christmas he had a cold and stayed home. On 29 December he went to his office to deal with correspondence, then wrapped himself up at home again. On New Year’s Eve he started to watch the Saturday night hockey game on television, but went to bed feeling unwell. There Alice Howe found him a short while later, dead of a heart attack.[31]

Howe’s Achievements at Dalhousie

Howe had been Dalhousie’s new chancellor for just three and a half years, but the changes he effected were considerable. The whole board was shaken up and invigorated, and in some important respects that applied to the whole university. Howe was a mover and shaker almost by instinct. He was not a lawyer trying to keep the status quo in balance but an engineer who aimed to make things work, improve them, make more efficient the world he moved in. For Howe, the means were less important than the end to be achieved, provided it was. He had little difficulty juggling several things at once. In the midst of working with Lady Dunn over her building, tenders were called for the new men’s residence at the end of March 1959. The lowest came in at $1,470,000; the building was to be in stone like the rest of the campus, though in Lake Echo shale, a more tractable stone than the ironstone prevalent elsewhere, and less expensive. Howe laid the cornerstone in October. He did not christen the building Howe Hall; a grateful board did after his death. New energy, new direction, new tone; “Daddy Atwood’s” canteen, after years of agitation, would at last be made over. The “Coffee House Revolution” went even further: the students were now encouraged to develop plans for a student union; that movement had started in 1957 when students voted $20,000 to establish the Student Union Building fund. The letter from Donald McInnes to Dave Matheson and Murray Fraser, co-chairmen of the building committee of the Student Council, on 27 November 1959, was positive: Dalhousie would provide the land; while the board could not help with the SUB immediately, having the Sir James Dunn Building and the men’s residence on hand, nevertheless the board would like to encourage the Student Council to proceed with the planning for it. This new positiveness by the board cannot be attributed wholly to Howe, but the vigorous responses to longstanding student concerns probably owed much to him. As the Gazette put it, “The Old Order Changeth.” In February 1960 the students voted 1,124 to 124 for a $10 fee increase to help pay for the SUB.

Howe’s positions at Dalhousie were academically sound, though politically to the right. He disliked the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT) and told Kerr to have as little as possible to do with it. He thought professors should keep out of politics, especially CCF politics. He did not appreciate J.H. Aitchison’s connections with CAUT or the Nova Scotia CCF. The growing muscle of the Dalhousie Faculty Association he seems not to have objected to; he knew doubtless that its rhetoric was justified by Dalhousie’s long delays in dealing with salaries.[32]

Some university chancellors are wealthy figureheads, but Howe was never that. He was more active than the Dalhousie board had quite bargained for; some thought of him in terms of the Nova Scotian definition of an expert: an s.o.b. from out of town. But he had played the important role of broker between Lady Dunn and Dalhousie, and he had helped in bringing Dalhousie to Mrs. Killam’s attention and interest. He knew the ways of the very rich. Altogether Howe’s vigour, realism, quickness, his protean range of interests and responsibilities, his ready knowledge of how the world worked, had all been deployed to Dalhousie’s great benefit. Even the appointment of Dalhousie’s new dean of arts and science in October 1960 had had Howe’s imprimatur and interest.

Dean Archibald had resigned on 18 October 1960, pleading ill health, though the real reasons were the frustrations of his office. G.E. Wilson was made acting dean, but it was clear that a new dean would be needed and at once. The president did not invite nominations; rather he resisted them. A number of senior men were possibilities, but Kerr sought out a much younger man, an historian, aged thirty-one, who had a decided knack for administration, Guy MacLean. MacLean was taken completely by surprise by the president’s suggestion that he consider being dean of arts and science; he asked for twenty-four hours to think it over. After discussing it with Wilson, MacLean had decided to accept the challenge. But when he came back to Kerr’s office, the president said that an important candidate downtown had come to his attention. Thus the suggestion was withdrawn.[33]

Henry Hicks Becomes Dean of Arts and Science

The downtown candidate was Henry Davies Hicks. Howe may have had a considerable hand in the choice; certainly he approved it. Hicks himself believed, however, that when President Kerr approached him about the deanship, the moving spirit in the nomination had been Frank Covert. Hicks, leader of the Nova Scotia Liberals, had just been defeated for a second time in the June 1960 provincial election by the incumbent Conservative premier, Robert Stanfield, losing his own seat in Annapolis East in the process. It was time, Hicks thought, to get out of politics and make some money in law practice. He approached two law firms in Halifax, one of which was glad to make room for him, Stewart, MacKeen, Covert, et al. But Frank Covert believed that Dalhousie needed new blood more than his law firm did, and thought of the recurring problem of the deanship of arts and science. Hicks would be an interesting possibility.

Hicks himself was not sure that he wanted it, but his younger brother urged him to take it. “Who remembers the governors of Massachusetts?” asked Duff Hicks, “but everyone remembers the presidents of Harvard.” What Dalhousie offered was not the presidency, certainly; but it was the deanship of arts and science, and the vice-presidency when C.L. Bennet retired in 1962. The vice-presidency was not important as long as Kerr was president, but for Hicks it was a foot in the door. The board would probably not have promised, informally or otherwise, the presidency of Dalhousie. What was being offered was opportunity; if Hicks should develop well as dean of arts and science, then he would certainly be a real possibility for president. Lady Dunn did not like what she had seen of Hicks, but Howe trusted the judgment of his board colleagues. Nevertheless he took the precaution of talking to Robert Stanfield, the premier, to ascertain that he would have no objections to the leader of the opposition being appointed dean of arts and science at Dalhousie. Stanfield said he had none at all.[34]

Hicks was a better candidate than he looked at first sight. Although he had only bachelor degrees, still there were four of them: Mount Allison (BA ’36), Dalhousie (B.Sc. ’37), Oxford (BA [Juris.] ’39, and BCL ’40). He had been minister of education under Angus L. Macdonald from 1949 to 1954, and in his own government when he was premier from 1954 to 1956. He had urged President Kerr in 1951 to insist on proper entrance qualifications for Dalhousie students, in order to remedy Dalhousie complaints about the quality of high school education. On the Board of Regents of Mount Allison since 1948, Hicks had been saying that Mount Allison needed to set higher standards, and any expansion of enrolment ought to take second place to that fundamental.

Dalhousie professors, especially those in Arts and Science, were rather taken aback by the choice of Hicks. They knew him mainly as a twice-defeated Liberal leader, having few academic credentials. While many in the faculty were willing to suspend judgment and risk the experiment, others were sceptical. Some were offended, if not outraged, by President Kerr’s procedure, by the very limited consultation the president had used. Kerr played his cards close to his chest but did talk privately to President Puxley of King’s on 19 October about his choices, saying none of the senior Dalhousie professors was qualified to be dean. Puxley urged Kerr to take faculty into his confidence, if only for morale:

If the Faculty sees that you do not care at all for their views or whether they have any confidence or not in your new appointee, you are bound to forfeit forever what remains of their interest in and loyalty to the University… My fear is that by appointing a complete outsider [Hicks] and/or one of the youngest and most junior members in the Faculty [MacLean], you will be “chastising them with scorpions”, it will finally stifle the loyalty of your older men… and will hasten the decline of the University.

A.S. Mowat, secretary of the Faculty Association, urged the president to consult senior men, suggesting J.H. Aitchison (Political Science), J.F. Graham (Economics), R.S. Cumming (Commerce), and F.R. Hayes (Biology). Kerr consulted Hayes, who did not say yes to Hicks but, according to Kerr, did so by implication. Two of those not consulted, Aitchison and Graham, plus James Doull of Classics, arranged to meet Hicks downtown to discuss the question. The three explained that they did not like the manner of Hicks’s appointment, and that while most of the faculty were probably willing to accept him, a minority, perhaps strong, opposed the mode and possibly the man that came with it. Hicks owed it to the faculty, and to himself, to ascertain their wishes. Hicks agreed to meet with faculty. There were others, former Dean Archibald among them, who urged Hicks to come anyway, that he would be accepted.[35]

Hicks was used to criticism. Politics requires a carapace, and Hicks was not seriously upset by the visitation of what he sometimes later called Dalhousie’s three wise men. But he paid attention to what they said about consultation. It is also fair to add that they did not attempt to frustrate his work, and they remained on friendly terms with him long afterwards. If there was some unease and coolness in the faculty, it gradually dissipated. In later years Hicks was not above teasing the three; on the other hand Hicks, who had been led by President Kerr to hope he might be allowed to lecture in political science, was resolutely prohibited from doing so by Professor Aitchison, the head of the department. The reason was not animus but academic credentials. Mere experience was not enough.

Hicks knew sufficiently little about the inner workings of his faculty that he relied on his Faculty Council for advice and consultation, and used them rather as he had his cabinet when he was premier. The faculty grew to like it. He also had a different view of money from the president; although his room for manoeuvre was restricted, he was more progressive, open, and generous. Moreover, having been minister of education for eight years, he knew something of education in the province, and he brought to bear on Dalhousie’s problems a range of knowledge informed by experience of Mount Allison and some of Acadia. This showed almost at once, when, ten weeks after he assumed office, he submitted his first report to President Kerr on the state of his faculty.

Before he came he had heard rumours that Arts and Science had fallen behind; what he had seen since confirmed it. In the departments of English, Mathematics, and Biology, staff/student ratios were double what they had been twenty years before. Hicks reported he would need thirty additional professors, and as soon as possible, and over the next five years Arts and Science would need to double its staff. Hicks offered the following table to the president of total faculty budgets against student numbers, showing expenditure per student by faculty and compared to Yale:

Dalhousie A & S Law Medicine Dentistry 1938-9 $259 $233 $432 $362 1948-9 265 251 873 922 1958-9 712 1,069 2,408 2,604 1960-1 696 1,720 3,100 3,410 Yale 1959-60 1,825 1,825 3,800

Hicks rubbed it in by comparing Dalhousie’s 1958-9 per capita expenditure on Arts and Science with Acadia’s and Mount Allison’s, $908 and $900 respectively. In 1960-1 Dalhousie would spend less for its 1,425 students in Arts and Science than did Mount Allison for its 1,061. Hicks concluded:

It seems quite evident that with its necessary and commendable concern for the reputation and quality of work in its professional faculties in the postwar years, Dalhousie has allowed its undergraduate Faculty of Arts and Science to become neglected. Today this Faculty, with more than two-thirds of the students in the University, expends about one-third of its budget, and this I understand includes the whole cost of carrying the University Library.

Hicks hoped to discuss his report as soon as possible, and enclosed extra copies in case Kerr should wish to submit it to the executive committee of the board. It would have been unlike Kerr to do so, and therein lay the fundamental problem. Kerr guarded that isthmus between the board and the rest of the university, and saw to it that such criticisms went no further. He did not like it at all when attempts were made to bypass him.

Three weeks later at Senate, the president said he had had no submission from Arts and Science. Hicks was surprised and pained at the president’s remarks, and wrote the next day a chiding letter. “May I suggest, with the greatest respect, Mr. President, that I doubt if you fully appreciate the low morale in the Faculty of Arts and Science.”

Old Howard Bronson of Physics, who had donated his property at LeMarchant Street and University Avenue to Dalhousie in 1950, wrote Kerr in much the same vein. When he came in 1910 Dalhousie was thought of by the Rockefeller and Carnegie people as the possible Johns Hopkins of Canada. Now, in spite of the new research facilities in the Dunn Building, physics lacked the professors to do good research. “Really good men… want to be proud to represent their University… I think the men in Law, Medicine and Dentistry now feel this way… but it certainly is not true of most of the members of the Arts and Science Faculty.”[36]

By this time the movement to define, regulate, and strengthen faculty and Senate influence in Dalhousie’s governance had gathered force. The most powerful expression of faculty restlessness was the appointment by Senate, on 8 December 1960, of its Committee on University Government, with a sweeping mandate to “review the present structure and practice of government at all levels within the University and to make recommendations thereon.” This was followed in 1961 by the creation of Senate Council, a working cabinet of Senate, which became operational in December 1961. In the late spring of 1962, as the Senate Committee on University Government gathered its documents, strength, reach, and determination, the president suffered a slight stroke. Dean Hicks took over as acting president until September 1962.

President Kerr Resigns

The board now decided it was time for Kerr to retire. When Donald McInnes told him so, it came as a shock. Although he was sixty-five years old, Kerr did not have to resign; his term was open-ended. But the fact was that he could no longer cope with the pressures and problems rising up around him. Unlike his predecessor in 1945, Kerr would go peacefully, and late in November he announced his resignation, effective 31 August 1963. The board expressed the regrets usual to such occasions, and singled out Nessie Kerr for special mention. She deserved it. She it was who had made Kerr’s presidency tolerable. Everyone liked her; she had gaiety and delight. She reminded one of Browning’s “My Last Duchess”:

…She had a heart – how shall I say? – too soon made glad, Too easily impressed; she liked whate’er She looked on, and her looks went everywhere.

Her life was not easy. At dinners Kerr would not only turn down his own wine glass but hers, when she would not have minded a glass of wine. He was angry when his son Donald married a charming Jewish girl, Lucille Calp of Saint John, and Kerr’s attitude was not temporary. Nessie Kerr also knew too well her husband’s standing in the Dalhousie community; the only dean who spoke well of him was another authoritarian, McLean of Dentistry. At a student concert given by the “Limelighters,” Kerr stood up and objected to the lyrics of one song, about a lady whose dress was up to the neck in front, “but so low in the back that it revealed a new cleavage.” Another president might well have ignored it. The students did not appreciate Kerr’s intervention and booed. He, of course, left. It is difficult to avoid feeling sorry for A.E. Kerr; he could not help his constricted Louisburg background that he never quite seemed to rise above. Though sufficiently endowed with intelligence, he lacked taste, style, manners. A devoted servant of the university, he conceived his duty within a hard, tight focus. Even the board had come to realize by the late 1950s that he was increasingly a liability. In short, the job grew but he did not, or not sufficiently.[37]

His talent lay in saving money, but it was often brutal or mesquin, pinching librarians’ salaries, or refusing the British Museum catalogue to the library. “Too rich for our blood,” he had said. Douglas Lochhead left Dalhousie because of a whole litany of such meaness. Kerr’s joy was in seeing buildings emerge from his economies; but in the end economies were his worst enemy as staff morale slowly crumbled around him.

Nor was he ever sufficiently seized of the autonomy of the university. There was an interesting incident in 1961. John Diefenbaker, the prime minister, came to speak at Dalhousie mainly about Canada’s role in world affairs. The crowd of students were polite but thought he neglected national issues. On the front page five days later the Gazette reported, “Mr. Diefenbaker said:…” and followed that with three inches of blank column. The Halifax Herald noted it and reproduced it on its front page a few weeks later. Diefenbaker saw it and he was furious. He promptly phoned Donald McInnes, who besides being chairman of the board was a leading Nova Scotia Conservative. McInnes phoned president Kerr, who summoned the president of the Student Council, and got Henry Hicks, the new dean of arts and science, to talk sternly to the editor, Michael Kirby. But Hicks relished the Gazette’s jibe, and his reprimand to Kirby had no weight in it. All he insisted on was a promise not to do it again.

A year later the Gazette came out with a comic edition; under the rubric, “John Causes Fall of Hall,” a front-page article, with a photograph of a urinal, suggested that the fixture had got installed in Shirreff Hall by mistake. The Gazette’s editor was Ian MacKenzie, son of Dr. Ian MacKenzie, professor of surgery. The father thought the Gazette issue tasteless, which it was; but the president was outraged and wanted MacKenzie expelled. The father was on the Senate Discipline Committee, and naturally stepped down when it heard his son’s case. But Senate refused to do anything.

In fighting the Gazette, Kerr usually lost. He had rows with three successive and able Gazette editors – Denis Stairs, Mike Kirby, and Ian MacKenzie. All three were trying to get a rise out of him and all three succeeded. A wiser man might have left well enough alone, and let Senate, or student opinion, take on the Gazette. The difficulty for the president was that the Gazette was read off-campus, and he invariably got the brunt of outside reactions, as with the Diefenbaker non-speech. But, unlike President Stanley MacKenzie or Carleton Stanley, Kerr’s attitudes came from wrong premises.[38]

The Board of Governors kept Kerr as long as they did owing to the enormous weight and momentum carried by a full-time president. Members of the board were always unpaid volunteers who, outside of board committees, rarely met more than once a month, sometimes less; under Darrell Laing, board meetings were apt to be dispatched in an hour. As Gordon Archibald remembered, Dr. Kerr would raise a subject and Laing would say something like, “Well that’s all settled, isn’t it, Dr. Kerr,” who would say “Yes” and the board would move to the next item. Meetings convened at 7:00 P.M. were often over by 8:00. Donald McInnes was a more phlegmatic and patient chairman, but he too liked to see the board agendas got through with celerity and without rancour.

McInnes also knew and liked Henry Hicks. It was not surprising that as early as December 1960, in reflecting about a new president for Dalhousie, old Jack Johnstone could say with his usual shrewdness,[39] “The rails are greased for Henry H.”

- See Robert Bothwell and William Kilbourn, C.D. Howe (Toronto 1979), pp. 36-7, 46-8, 277, 332-4; Lord Beaverbrook, Courage: The Story of Sir James Dunn (Fredericton 1961), pp. 202, 268. Relations between Dunn and Howe, as well as a judicious survey of Dunn’s business history, are set out in Duncan McDowall, Steel at the Sault: Francis H. Clergue, Sir James Dunn and the Algoma Steel Corporation 1910-1956 (Toronto 1984). Lord Beaverbrook (1879-1964) has several biographies. The best and most recent is Anne Chisholm and Michael Davie, Beaverbrook: A Life (London 1992). His comment on Lady Dunn in 1956 (p. 508), is taken from Richard Cockett, ed., My Dear Max, The Letters of Brendan Bracken to Lord Beaverbrook (London 1990), p. 50. ↵

- Letter from Kerr to C.D. Howe, 8 Aug. 1957, President's Office Fonds, “C.D. Howe, 1957-1959,” UA-3, Box 350, Folder 1, Dalhousie University Archives; Board of Governors Minutes, 22, 29 Aug. 1957, UA-1, Box 51, Folder 1, Dalhousie University Archives. For Howe, see especially, Edith MacMechan to Howe, 30 Aug. 1957, from Chester; Howe to Edith MacMechan, 9 Sept. 1957, C.D. Howe Fonds, Library and Archives Canada. Mrs. MacMechan reflected how pleased Archie would have been that Howe was being made chancellor. For Professor Archibald MacMechan, see also Peter B. Waite, Lives of Dalhousie University, Volume 1, especially pp. 159-61, 206-7. The first mention of Howe as a possibility for the Dalhousie board is in memorandum, Kerr to Laing, 28 June 1957, President’s Office Fonds, “H.V.D. Laing 1949-1958,” UA-3, Box 335, Folder 4, Dalhousie University Archives. This is a list of twenty-six items discussed between them. The replacement of Sir James by Howe seems to have been raised by Laing. Kerr’s question was whether Howe considered himself a citizen of New Brunswick. The important correspondence with Lady Dunn is Lady Dunn to Howe, 29 Aug. 1957, Howe to Lady Dunn, 29 Aug. 1957, C.D. Howe Fonds, Library and Archives Canada. Both letters originate in St. Andrews and may have been delivered by hand. The use of the C.D. Howe Fonds, so important for this chapter, was made possible by the kind permission of his son, William H. Howe ('40). ↵

- The report on the construction defects in the Arts and Administration Building is in President’s Office Fonds, “Buildings, Arts and Administration,” UA-3, Box 233, Folder 7, Dalhousie University Archives, D.A. Gray and Co., n.d., but probably Apr. 1956. The report was especially critical of the mortar, both in its quality and application. For Mathers & Haldenby, see Board of Governors Minutes, 12 Feb., 20 June, 19 Sept. 1957, UA-1, Box 51, Folder 1, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- Letter from Lady Dunn to Howe, 24 Dec. 1957, from St. Andrews; Howe to Lady Dunn, 30 Dec. 1957, C.D. Howe Fonds, Library and Archives Canada. ↵