3 New Building, Silent Rooms, 1821-1837

Divisions between Nova Scotian colleges. Sir James Kempt. Finishing the building. Proposal to unite Dalhousie and King’s College, 1823-4. Nova Scotia’s Executive Council and Colonial Office pressure for college union.

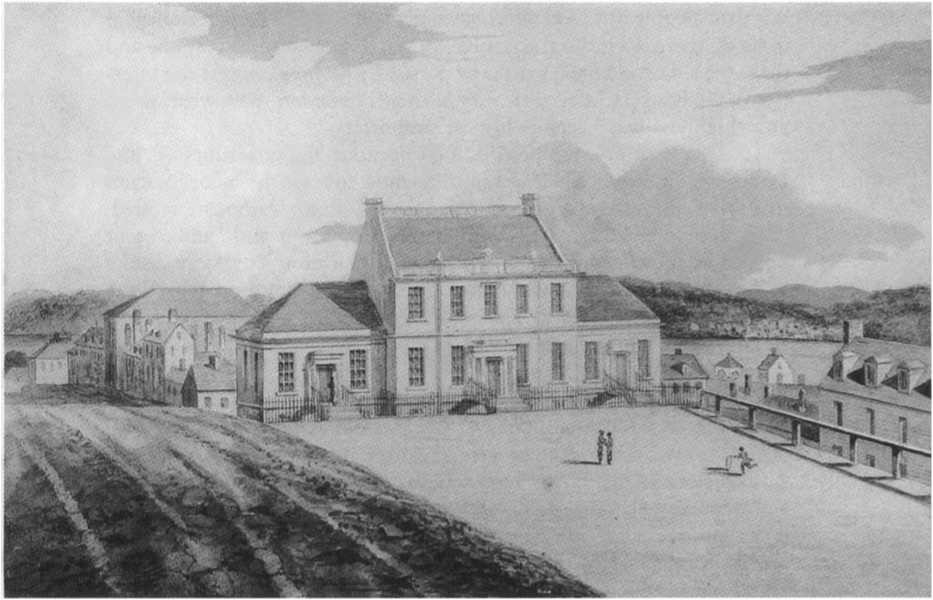

Like Julius Caesar’s Gaul, Nova Scotia’s college geography in 1821 was divided into three parts, all different. King’s in Windsor had a fine royal charter and a decrepit wooden building; it was also riven by personal feuds rather more damaging than its building. The second, Pictou Academy, had no charter as a college, but had a useful building and great ambitions. The third part was Dalhousie College, with a handsome new (and expensive) stone building right in the middle of Halifax, almost finished, but having neither principal, staff, nor students – nothing in fact except £8,289.9s.6d. invested in London, a growing debt in Halifax, and that fine property on the Grand Parade.

Sir James Kempt knew this only too well. But he was of Lord Dalhousie’s mind, that a metropolitan college in the capital was the best, the only, answer to the potential of a three-way split. Sir James was not perhaps as intellectually vigorous as Dalhousie; the long correspondence between them is like that between the head groundsman and the lord of the manor. Still, Kempt had strengths that Dalhousie had not: he was affable, tractable, sensible, disposed now and then to be disarmingly hypocritical. He thus worked well with local politicians, especially with Simon Bradstreet Robie, the Speaker of the Assembly, whom Lord Dalhousie had sometimes thought of as a low, conniving fellow. Kempt was not a bad hand at conniving himself, when needed.

He was a fifty-five-year-old bachelor, born and raised in Edinburgh, with a fine military record. In Halifax he developed a reputation as rather a gay (in the old-fashioned meaning) blade, disposed to having pretty women around Government House, one of whom was a famous and beautiful grass widow, Mrs. Logan. He was liked for his parties and his vivacity. High-toned he was not. Like his predecessor, Kempt was also a great traveller, but rather more practical, having a penchant for making good roads. The Kempt Road in Halifax marks that proclivity.[1]

Lord Dalhousie remarked from the heights of the Quebec Citadel that in only two respects had the Assembly of Nova Scotia disappointed him. They had secretly opposed his wishes on militia appropriations; and their same “want of candour and honesty” was evident with his new college. What he meant was that the Assembly’s willing acceptance of his initiative in creating the college was followed by a lamentable lack of support for proceeding with it.[2] Lord Dalhousie had wanted it to be the college of Nova Scotia, with King’s hived off for that 20 per cent Anglican constituency. The Assembly, riven by its own loyalties, prejudices, and fixations, became difficult, if not impossible, to arouse on the subject of a non-denominational college.

Kempt had been asked to keep a close eye on the building. He did more than that; he positively badgered the engineer, Lieutenant Gregory of the Royal Engineers, and the treasurer of the province, Michael Wallace, to get on with the work, and, even more, to present accounts. By the end of the 1820 working season in November, the stone work was finished, both wings were roofed and slated in, and all that remained was the slating of the centre roof, which could not be finished until the pediment was up. By now it was obvious that the costs would outrun the money available in Halifax, notwithstanding attention to economy – consistent, that is, with the magnitude of the work. Kempt thought the whole building looked very handsome, and it was going to be “a great ornament to the town.”[3]

By January 1821 it was clear that the building was about £3,000 beyond the money available. Kempt called a meeting with S.S. Blowers, the chief justice, Michael Wallace, and Speaker Robie, to consider ways and means. With debt now accumulating it was expedient to incorporate the governors of the college. These now were: Lord Dalhousie, Sir James Kempt (or the lieutenant-governor of Nova Scotia, whoever he was), the Anglican Bishop of Nova Scotia, the chief justice, the treasurer of the province, the Speaker of the Assembly, and a president of the college, yet to be named. The 1821 bill for incorporation passed the Council first, then went to the Assembly. The original bill had incorporated in it a promise to donate a further £2,750, above the £2,000 given in 1819, but the Assembly deleted that. £2,000 was enough. At that point two MLAs brought forward a petition from Pictou Academy asking for government aid. Nor was that all: “the Windsor people are as clamorous to get some aid to King’s College – in short, there is a general scramble for the three Institutions at one and the same time, and there are many persons who now express the interests of Dalhousie College in a very lukewarm manner, who were, when your highness was here, its firmest supporters.”[4]

The 1821 statute was passed, incorporating the governors of “the Dalhousie College.” The chief justice sent a copy of the incorporation to Lord Dalhousie at Quebec. “You have,” Lord Dalhousie replied, “as you threatened me, placed my name in the front rank, and to that post of honour I cannot possibly have any objection – my only dislike to be so put forward, was in the apparent presumption which the world will ascribe to me.” The costs were making him uneasy. So far, so good; but what of the next stage?

[I]s this child of my hopes to be cut off in its birth? I should be inclined to charge my good friends Wallace and Gregory with the murder, if it so happens. I was well aware that we were working beyond our means, and I earnestly pressed those gentlemen to a serious calculation of what we had done, and what we were going to do this last Summer. Nothing of that sort was done, and now we are deep indeed in difficulties, although I trust not quite beyond our depth.[5]

Dalhousie College’s official legal existence began during the coldest January in living memory. The harbour was frozen over as far out as McNab’s Island. Ships could come in no further than York Redoubt; one ship had to be cut out of the harbour for two miles by a military working party. Sleighs went everywhere over the harbour ice.[6] It was a chill that seemed to affect the Assembly. Kempt urged them in a special message in February 1821 to vote money for Dalhousie College. Robie was willing enough, but he had to fight what Kempt called “a great indisposition” on the part of the Assembly. The best they could do was to revive an offer made in 1820. As a parting gesture the Assembly had in April 1820 offered Lord Dalhousie £1,000 to buy the Star and Sword for his GCB, which were both expensive, the Star especially. At that point Lord Dalhousie was angry with the Assembly for omitting, surreptitiously, an appropriation for militia inspection and had refused the gift. Kempt ingeniously suggested that this £1,000 be given to Dalhousie College instead, a dignified way of disposing of the money, and one that would gratify Lord Dalhousie. That was done. Still, it annoyed Kempt that the Assembly gave £400 to Pictou Academy without any urging from him at all. Technically he could have blocked it, but to have done so would have created great irritation and ill-humour. That was not Kempt’s style.[7]

Negotiations about a principal for the college went forward as slowly as the building. In October 1821 Lord Dalhousie learned that it was a matter of money; able men could make much more money in England without having to emigrate to the colonies. Lord Dalhousie’s correspondent added that “certainty of church preferment would be a great inducement.”[8] It was just this that Lord Dalhousie wished to avoid.

For a time Kempt had hopes that the colonial secretary could be persuaded to give the crown’s coal revenues from Nova Scotia to aid what should become the main provincial college and university, but Lord Bathurst demurred. Kempt suspected the hands of John Inglis and Bishop Stanser in helping to kill that excellent idea. Inglis was, in Kempt’s opinion, a most cunning ecclesiastic, whose indefatigability equalled his guile; as for Bishop Stanser, he had been living in England since 1816 on his bishop’s salary doing nothing at all.[9]

By this time, January 1823, some £5,000 was needed to pay the debt on the Dalhousie building. Kempt tried to force the pace with his Board of Governors, but they were not having it. They felt they ought to rest on their oars now that the building was finished, at least until some way might be devised for getting rid of the debt. This was not to Kempt’s mind a very sound way of going forward; he gloomily reflected that the building of the college had been done most injudiciously. It was not that the building was not well made – it was; but it had been done with little regard for time and money.

Lord Dalhousie in Quebec agreed. He too was gloomy and disappointed. He thought the very worst thing for the college was to stand still. Perhaps the whole thing should be abandoned. The debt was in any case secured by the capital fund invested in London. Giving that up would mean the end to a noble dream, but perhaps, he said, Nova Scotia was not ready for it:

If the idea of a College in Halifax is pronounced to be premature, be it so. Make that building then a Grammar School, or anything so that it may in some way be useful… when the parents of Halifax shall see the advantage of an Institution more comprehensive for education than a common school then the College charter may venture to raise its head from the grave, to which the present generation has committed it … In all the share that I have had in that Institution, there is only one point, which gives me any regret, and that is, that I was over persuaded by the good Chief Justice and Mr. Wallace to allow my name to be given to it in the Charter. I always felt and thought it an impropriety, and I am convinced it has produced ill-will and opposition to it. From the interest I shall ever feel in its progress, I cannot but be vexed, and disappointed in its premature decay.[10]

It was not quite as bad as that. Robie pulled together some support in the Assembly and Kempt fired off a bold message on 25 March 1823, asking that a loan or some other means be given to Dalhousie College to allow it to pay the debts incurred in its building. It would be, after all, a college open to all denominations; it was not the rival of any other college. It was, said Kempt, “the friend and co-relative of all. I cannot but flatter myself,” he concluded, “that it will not be suffered to be stifled in its infancy, and so promising an object, after the great expense already incurred on it, to be rendered useless and abortive.”[11]

Kempt hoped that would rally the Assembly, though he warned Lord Dalhousie the next day that no great confidence should be placed in a lower house “subject to be veered about by every wind that blows.” And the opposition to Dalhousie College now met with in Halifax, he added, “is not to be believed.” John Inglis had, Kempt thought, poisoned the institution’s whole constituency.[12]

The Assembly took its time. The question of more money to Dalhousie College was postponed for ten days; finally on 4 April there emerged from Committee of the Whole a resolution that £5,000 should be loaned, not given, to Dalhousie, for five years, without interest. Repayment would be secured by the capital fund of the college invested in England. It passed the Assembly by a vote of twenty-three to eleven. The opposition to any money being offered at all came mainly from the Annapolis valley.[13]

This seems to have tipped the scales in King’s consideration of a possible union with Dalhousie. King’s with a dilapidated building did have professors and students, though not many of either; Dalhousie College with a handsome new building had neither professors nor students. It was obvious policy to think of uniting the two colleges. Such a union would certainly forestall the ambitions of Pictou Academy! Thomas McCulloch of Pictou Academy had already been warning Dr. Inglis about the danger to King’s of Dalhousie College, that it would affect King’s far more than Pictou Academy ever could or would. Kempt now promoted union actively, and being on the boards of both colleges, he could do something about it.[14]

A King’s committee was struck in September 1823; they met a committee from Dalhousie, and this was followed by a joint meeting at Government House, Halifax, in January 1824.

The resolutions that emerged from that meeting envisaged a wholly new college, with a new name, “The United Colleges of King’s and Dalhousie,” in Halifax. The structure was very like that of King’s, the president to be an Anglican clergyman, and three or more fellows were also to be Anglican (and unmarried). Those were concessions the Dalhousie board made. On the other hand, Dalhousie College got the professorships, and students, open to any qualified person, of whatever religion; there were also no rules requiring student residence in college. The general aim was to put an end to King’s-Dalhousie rivalry. As Inglis put it, to keep up that rivalry would keep both institutions in “poverty and insignificance, because it must be evident that one college will be ample for the literary wants of Nova Scotia, and perhaps of the adjoining provinces, for several centuries.”[15]

Lord Dalhousie was delighted with these discussions. Now that union was proposed, he was willing that his own name should disappear and the new united college be called only King’s. He felt his name, and that of King’s, should not be equated by thus being put in apposition.[16] But Lord Dalhousie’s enthusiasm for union was not matched by some governors of King’s, notably the chief justice. Blowers stressed the Oxford traditions behind King’s, how Oxford enjoyed learned leisure, in peace and tranquillity, far from noisy crowds, far from “the hurry and bustle of trade – and the dissipation, extravagances and bad example of the idle.” His other objection was more philosophically pertinent: that the union was an attempt to engraft King’s upon a college of quite dissimilar design. Classics was the core of the King’s curriculum; at the joint college, classics might well be made subservient to more diffuse interests, that “classical education may be lost in the more showy and dazzling employment of [scientific] experiments and amusing pursuits.”[17]

Lord Dalhousie scoffed at these objections. That the morals of King’s students would suffer in Halifax, he simply dismissed out of hand. In his experience, Windsor and its surroundings were not remarkable for moral tone. “And I maintain, as proof of my argument, that the studious and quiet habits of the students in the City of Edinburgh form a striking contrast to the gay, hunting, riding, driving, extravagant expenses of the young men at the English universities.”[18]

Notwithstanding the objections of the chief justice, the majority of the King’s governors were in favour of union. Early in 1824 a bill was drafted to join the two colleges. It would not go to the legislature yet; drafts would be sent to the Archbishop of Canterbury and to Lord Bathurst. John Inglis went over to help things along. Kempt thought Inglis was sincere in the cause of union. After all, King’s had officers, energy, and a religious constituency; now it would have a building and metropolitan students. But the Archbishop of Canterbury had other advisers, not the least of whom was Sir Alexander Croke. Croke, of Oriel College, Oxford, had been vice-admiralty court judge in Halifax and had lived on an estate in the Halifax western suburbs, overlooking the North-West Arm. He was an unrelenting Anglican. It was he, with Bishop Charles Inglis and Chief Justice Blowers, who had once put into the King’s rules that all entering students had to subscribe to the thirty-nine Articles. The archbishop was thus relying upon a person who had succeeded in making himself the most unpopular man in the province.[19]

From whatever influences, or perhaps from his own convictions, the Archbishop of Canterbury refused to accept the proposed union of King’s and Dalhousie. When Lord Bathurst concurred in that refusal, the union was dead, at least in the lifetime of those two officials.

Sir James Kempt had not given up hope for the coal-mine revenues for Dalhousie College, and his importuning finally bore fruit late in 1823. The colonial secretary offered £1,000 to both King’s and Dalhousie from that source. It was on one condition: that the Assembly match both grants with equal amounts. This offer the Assembly received with considerable coolness. It got Kempt’s message in January 1824, and replied to it on the very last day of the session, two months later. The Assembly said it was proposing to review all education grants in the 1825 session, and Lord Bathurst’s despatch would be considered then. Then nothing was heard of the subject from the Assembly for five years.

To What Purpose?

By 1824 the Dalhousie College building stood completed at the north end of the Grand Parade, but it stood empty. The governors left matters at a standstill while union with King’s was being proposed, ventilated, and eventually rejected. They kept hoping for money, encouraged by Kempt’s ineradicable belief that Lord Bathurst could be persuaded to part with the crown revenue from the Nova Scotia coal mines. In the meantime, the Dalhousie College board hired no one, and opened nothing; they did not have sufficient income from endowment with which to pay any salaries. Dalhousie’s capital fund was £8,289-9s.6d. invested in 3 per cent Consols in London. It brought in precisely £248.13s.8d. per annum, not enough remuneration for any good principal. As of 12 June 1822, the cost of the building was £11,806.2s.0d.; the final cost was £13,707.18s.3d.[20] An accurate estimate of what this means in contemporary 1990s terms is virtually impossible, but since something is better than nothing, the final cost would represent something like $3 million.[21] It was a great deal of money for one building.

Kempt, in London in the summer of 1825, reported that the Archbishop of Canterbury was still obdurate against any union of the colleges. He also noted that Inglis, since March of 1825 Bishop of Nova Scotia, had in that capacity collected about £2,000 for King’s. The failure of union was a great triumph, Kempt reported, to Thomas McCulloch “and his Gang” at Pictou. Old Michael Wallace, of the Auld Kirk, who hated McCulloch and all his works, would, said Kempt, have a heart attack when he heard that result.[22]

McCulloch had not been idle; he never was. He wrote Lord Dalhousie at Quebec in September 1823, urging that Dalhousie College, if it were to prosper, would have to be attached to some religious denomination. The Anglicans, he warned, would never give Dalhousie College a fair shake, in or out of union, on any matter academic or otherwise, that might interfere with King’s needs or King’s welfare. Why not, urged McCulloch, put Dalhousie College under the guardianship of the Nova Scotia Presbyterians? Lord Dalhousie replied that to do that would put King’s and Dalhousie in a state of perpetual war. His object, he told McCulloch, was to erase all distinctions in higher education in Nova Scotia, so that Protestant and Catholic, Presbyterian and Episcopalian, would all be accepted on the same terms.

But there was more to McCulloch’s argument than Lord Dalhousie would allow. It goes to the heart of the difficulty his college was now facing. McCulloch emphasized:

Indeed no well regulated church will be disposed to receive its teachers from a seminary for the soundness of whose principles it can have no guarantee. And it appears to me that the Dalhousie College is most likely to be under the control of persons who with views and feelings inclined to the established Church will not be very apt either to consult the success of the seminary which seems to interfere with the favorite institution of their own religious society … Thus it would seem that while that seminary [Dalhousie College] is unconnected with any religious body having an interest in its prosperity it is exposed to the attacks of those who are both enterprising and powerful.[23]

The truth was that right across British North America the influence of the churches in education was pervasive and powerful. A college with no denomination behind it, in a world where denominational rivalries and loyalties were a fundamental way of life, was almost doomed. In an age of such intense religious convictions, upon whose loyalty and support could an open, tolerant, non-aligned college depend?

So Dalhousie College languished. A room for a steward is recorded as having been established in December 1825, and in the summer of 1826, by some unrecorded informal arrangement, it agreed to rent out vacant rooms. John Leonhard, a confectioner, rented the northeast corner rooms on the Barrington Street level. In the Assembly session of 1827 Thomas Chandler Haliburton, a King’s graduate be it remembered, referred in a fit of temper to “the Pastry Cook’s shop called Dalhousie College.”[24] The air of almost deliberate negligence annoyed Philip John Holland, editor of the Acadian Recorder, and his impatience showed in an editorial on 27 October 1827:

Months and years have passed and our ears have again and again greeted the joyful report that this institution would very soon open its doors… We [now] pass it without thinking of the purposes to which it should be applied and for which it was built… Where, we ask, lies the fault? It was planned, wisely in our opinion, by Lord Dalhousie. If those who supported him thought otherwise, and determined at a future time to withdraw that support, they betrayed the interest of the province most shamefully… If the design be good, why has it not been forwarded? and why has so large a sum been expended to no purpose? … As to the utility of a college in Halifax no serious objections have been stated openly or candidly; nor do any seem to be entertained except by those who are fearful of its interference with other institutions, and who in an indirect manner oppose its success. Of its injuring the Windsor or Pictou institutions there cannot be the smallest apprehension … is Halifax to be the only place considered unworthy of possessing a learned institution?

Thus it was that D.C. Harvey felt impelled to write the oft-quoted sentence in his 1938 Dalhousie history: “Dalhousie College was an idea prematurely born into an alien and unfriendly world, deserted by its parents, betrayed by its guardians, and through its minority abused by its friends and enemies alike.”[25]

t is not difficult to contrive conspiracies out of this strange tale of cost overruns and delays, with nothing to show for it after a decade and £13,000 but an empty building with a pastry shop in the bottom corner. The great expense of the building itself, the apparent absence of any strong, positive, active interest on the part of the Board of Governors, makes it look as if Lord Dalhousie, Philip Holland, and D.C. Harvey were right in suspecting something was very much amiss. Was it not true that of the six-man Board of Governors, the chief justice, and the Anglican bishop were vitally interested in that other institution, King’s? Was it not evidence of Lord Dalhousie’s incapacity as a judge of men to appoint men to the Dalhousie board already on the King’s board? These are baleful questions that lie unquiet in the mind and are not easily put to rest.

The expense is undeniable; the college could have been built at least one-third cheaper had it been started in 1823 instead of 1819 just after two major wars, when prices were still high. There is also good evidence that Lord Dalhousie was persuaded to expand the original plan of a one-storey design, as hopes for union with King’s developed in 1820 and 1821. That probably explains the rather attractive second-storey addition, giving life to an otherwise low and not very distinguished front.[26]

Nevertheless straightforward answers are possible. Lord Dalhousie did not want an absentee board of governors, but preferred people in Halifax who could act and work. He also seriously underestimated the importance of religious affiliation, of local resistance to a “godless” college, and how difficult it would be for a college with no denominational backing whatever to develop roots of its own. Even the new University of London, created for the same reasons as Dalhousie College, had difficulties; after it was started in 1828, it was forced to create King’s College, an Anglican establishment, within it. In short, Lord Dalhousie could command, could create; he could not furnish an enthusiastic or loyal constituency for his college.

But there is something more. Lord Dalhousie had received some support for his ideas from his Council, and tacit, though grudging, support from the Assembly in 1820. The real problem with his college may well have been in the Council. Lord Dalhousie was conservative by habit and thought; Nova Scotia was his first posting as a civil governor and in the coinciding of his ideas with his Council’s at many points, he may well have misread the men themselves. He got along well with them; they were of his world and manners, and that made his misreading all the easier. Most of them had been in office, and would so remain, for a long time. Blowers had been on Council since 1797 and would stay until 1833. Richard Uniacke was attorney general from 1797 to 1830, treasurer Michael Wallace the same. They and their nine other colleagues were the government; no one got an appointment to office without being nominated by one of them. Of the twelve members of Council in 1830 at least five were related by marriage and family. Judge Brenton Halliburton, perhaps its ablest member, was appointed to Council in 1815 by Sir John Sherbrooke; he was married to Bishop Charles Inglis’s daughter. By 1830, Halliburton’s father, two uncles, his father-in-law, two brothers-in-law, his son-in-law (plus three other assorted relations) had all had seats on the Council at one time or other, and five were members at the same time.[27] Halliburton’s boisterous abilities were well liked by Lord Dalhousie; he was distinguished, as Dalhousie pointed out, “by great fluency of conversation, and a loud and vulgar laugh at every word.” His law was not extensive but, like his wine, it was of the very best quality.[28] Halliburton’s group knew each other well, and they shared views about politics and society. Most were Anglicans, although Wallace was a Kirk Presbyterian; they had seen several governors come and go, each with their own penchants and peculiarities.

The Council thus knew perfectly well how to handle governors. Give them their head a bit, let them gallop around with their own peculiar interests for a while; if they press something they want very much, let them have it – on principle. But take care that the Council control the practice. Dalhousie College is a case in point. Lord Dalhousie had found his Council accepting his ideas; they would not set their will against the governor’s. They did not have to. They could recover any ground in their own sweet way, in their own good time, and there was lots of that. Thus it was that Dalhousie College was betrayed by its guardians, for its guardians neither really believed in it, nor were sincere in wanting it. The Council had simply bided its time, allowing natural difficulties their way, even abetting them from time to time. A few years later, in 1843, Joseph Howe commented on this very point:

It appears to have been the fate of this Institution [Dalhousie College] to have had foisted into its management those who were hostile to its interests; whose names were in its trust, but whose hearts were in other institutions. These, if they did nothing against, took care to do nothing for it – their object was to smother it with indifference.[29]

The Assembly was not much more charitable, though a good deal more open. In 1829 a resolution was proposed that the £5,000 loan of 1823 be called in. Beamish Murdoch, historian and lawyer, moved in amendment that the £5,000 be left with Dalhousie, provided the college be put into operation according to its original design within some reasonable period. Murdoch’s amendment was defeated, and the original motion passed by eighteen votes to nine.[30]

This put the governors of the college fairly up against it. They did not have £5,000 on hand, except that endowment in London. They had made efforts to find a principal; the most promising candidate was Dr. J.S. Memes of Ayr Grammar School, Scotland, recommended by Lord Dalhousie. Correspondence with Dr. Memes opened in 1828; but the Assembly resolution forced the governors to back away for the time being, though still holding out hopes that they would be able to open the college ere long. Lord Dalhousie, now in England and about to leave as governor general of India, wrote the governors that he could raise £500 himself, and might be able to promise £500 annually. But in the autumn of 1829 they authorized the secretary to put any rooms in the college that were vacant and unoccupied out to rent to the highest bidder.[31]

At the 1830 session of the Assembly Michael Wallace gave a long- awaited report on the college. On the east end of the building there was a grammar school of fifty-five boys, on the west a painting school. The pastry cook remained. There was income from those rentals. The capital sum of the endowment was, however, not under the control of the governors, but under a triumvirate: Lord Dalhousie, Chief Justice Blowers, and Michael Wallace himself. The governors were only authorized to receive the dividends from the London agents, Morland, Duckett and Co. If the Assembly were to insist upon getting their £5,000, the sale of the building and the Parade adjoining would probably bring in that much; but Wallace could not bring himself to believe that “the Assembly could be disposed thus to annihilate the plan adopted by Lord Dalhousie for the promotion of useful learning in the Town of Halifax.” He asked the Assembly to postpone collecting the money until a more propitious time. Indeed, said Wallace, the college was about to start; a principal had already been selected and was waiting to come out to Halifax.[32]

The Assembly was none too willing. Lawrence Hartshorne moved that the £5,000 be forgiven Dalhousie College, but that went down overwhelmingly. James Boyle Uniacke moved that the loan not be called in, since hope now was that the college would open in a year. That, too, was defeated. Alexander Stewart (liberal but shifting gradually to the right) moved that Dalhousie be given three years to pay its debt. That the Assembly accepted.

With three years’ grace now available to them, the Dalhousie governors took only four days to decide to ask Dr. Memes to come as principal, and as soon as possible. His salary was to be £300 a year plus an estimated £100 or so from student fees. A delay then ensued, and there is some evidence that the Dalhousie governors wanted Dr. Memes ordained first. He was a lay person, not a divine; he was famous for his books, the Memoirs of the Empress Josephine, and a Life of Canova, the Italian sculptor. These works, estimable no doubt, did not have the right ring to them. In British North America, college principals then (and later) were usually men of the cloth. McGill broke this tradition in 1852 when it appointed a lawyer as principal, and more dramatically in 1855 when it appointed J.W. Dawson, a scientist, of Pictou County, who would remain until 1893. But in 1830 ministers were the rule; ordination for Memes was a form of insurance. Dr. Memes gave up Ayr Grammar School as of 1 October 1831, and was proposing to embark for Halifax on the 12th.[33]

The Colonial Office Intervenes

But he never did sail. The Colonial Office intervened; it now revived the idea of Dalhousie’s union with King’s. The old Archbishop of Canterbury, Charles Manners-Sutton, had gone to his heavenly reward in 1828, and the former colonial secretary, Lord Bathurst, had gone to being president of the Council. Sir George Murray, the new colonial secretary, now determined that King’s would be united with Dalhousie. The weight of his opinion – and of his four successors in that office – now swung portentously behind the project. If that were to happen, it had always been understood by King’s (and Dalhousie) as a prior condition that Dr Charles Porter, president of King’s since 1807, would be president of the united college. Porter was, moreover, Michael Wallace’s son-in-law, and that connection helped to strengthen his present, and future, position. It also left Dr. Memes in Ayr.

The Colonial Office had fat files on the two Nova Scotia colleges, and on Pictou Academy, not all of it accurate, some of it naive, and most of it grossly underestimating the strength of intense religious loyalties in Nova Scotia. As administrators often would, the Colonial Office officials assumed that the rationality of their proposals would automatically recommend them to any thinking legislator or voter. Sir George Murray in 1829 opened up several options. One was selling Dalhousie College lock, stock, and barrel, and after its debts were paid, giving the funds that remained to King’s. Alternatively, he suggested that King’s could move to Halifax into the Dalhousie College building. Amid these brutal options he pointed out the great inconvenience of college schemes that were too expensive for the purpose, “so strongly exemplified in the case of Dalhousie College.”[34]

His successor, Viscount Goderich, was more decisive. The annual £1,000 British parliamentary grant to King’s would be halved in 1833 and terminated altogether in 1834. He thought the Assembly should not ask for, nor expect, repayment of the £5,000 from Dalhousie College. The boards of governors of the two colleges met in January 1832 in Halifax to consider the full implications of this verdict. Union proposals emerged on virtually the same basis as those of 1823. The Speaker of the House, S.G.W. Archibald, on both boards, dissented from this decision, not liking the contradictions of two quite different systems patched together, arguing that a constitution of the two colleges would need legislation.[35]

Sir Peregrine Maitland, lieutenant-governor from 1828 to 1832, was thin, austere, and Methodist. But he was also a realist, and was quite certain that a union between King’s and Dalhousie was essential, and the sooner the better. Dalhousie College, he said, “possesses a substantial building in a state of great forwardness, and a Constitution… well suited to the wants of the Province and to the opinions which are prevalent in British North America.” The Assembly was becoming clamorous for the repayment of the Dalhousie loan, and it has not so far shown much disposition to be indulgent to a college which, after all, was “to be perfectly open to all religions.”[36]

King’s was also getting a union on virtually its own terms. As in 1823, union was conditional on its Anglican exclusiveness being transferred to Halifax. In effect, Dalhousie would be made a non-sectarian section of King’s College, Halifax, with Charles Porter as president. To those King’s terms, Lord Goderich was unhelpful and unrepentant. Never mind that the Dalhousie College board had been willing to give up its individuality to King’s; in effect Goderich agreed with S.G.W. Archibald, that the Nova Scotian legislature would have to be the arbiter of such a college union, and that union was not to be saddled with terms the legislature could not or would not accept. Goderich’s successor, Lord Glenelg, was even more firm, deploring King’s resistance to the only measure that, in Glenelg’s view, could put colleges in Nova Scotia on a sensible basis. Glenelg even talked of recommending to William IV that the King’s royal charter be annulled. It was, said Glenelg, a question of “the existence of any College at all in the Province.”[37]

King’s now fell upon dark days. In vain was Dr. Porter sent to England to plead its cause. By 1834 the parliamentary grant was cut off, and all King’s had left was the annual £400 sterling from the Nova Scotia legislature. King’s went on determinedly, with four students. It reminded G.G. Patterson of the story of the bull that attacked an oncoming railway engine: courage admirable, judgment wanting![38]

Dalhousie, King’s and Pictou Academy

The lieutenant-governor now on the scene in Halifax was Sir Colin Campbell, who came in July 1834. Like his predecessors, Sir Colin was a military man who had served in Spain and at Waterloo. He was fifty-eight years old, gregarious and hearty. His weakness was his political baggage: he had too many old prejudices; he was not skilled enough to deal with questions on their merits, and he preferred to rely on local advice which was too often self-interested and strongly conservative. He was, in short, naive, friendly, and in some circumstances dangerous. At first he enjoyed a good deal of local popularity, and was soon the patron of a host of local organizations. He braved the cholera epidemic of 1834, and won plaudits for visiting its victims at the Dalhousie College cholera hospital and elsewhere.

The cholera epidemic had been brought to the Maritimes by immigrants in festering ships, and not even isolation on McNab’s Island could contain it. It was spread by unclean drinking water, especially in summer. Halifax still got its drinking water from wells; good fresh water from Long Lake would be brought to town only in 1847.

Cholera was an ugly and dangerous disease, striking with little or no warning; by the time you knew you had it, it was often too late. It broke out in August 1834, and by the end of that month there were thirty-five new cases and fifteen deaths every day. About one-third of the cholera victims were treated at the Dalhousie College cholera hospital, the rest at home. By the end of September the epidemic was waning, but by then some four hundred people, out of Halifax’s population of fourteen thousand, had died.[39]

Two large rooms at the west end of the Dalhousie building had been rented to the Mechanics Institute in 1833, to be given up on a week’s notice, as doubtless they were during the cholera epidemic. But the Mechanics Institute returned, and through organizing and sponsoring lectures and meetings on a great variety of subjects, became what Howe was to call the “University of Halifax.” By the end of the 1830s it had become the Halifax community centre, not a bad function. When Dr. Thomas McCulloch came to lecture at the Mechanics Institute on affinities between chemicals, fifty people had to be turned away.[40]

McCulloch was already anticipating that Pictou Academy might not be able to go on in its present form. It had fallen upon darker days, too. In the past its difficulties owed much to the hatred of it by the Auld Kirk in Pictou and their influential ally in Halifax, Michael Wallace. Wallace died in October 1831, aged eighty-seven, irritable, unyielding, but powerful to the end. Lord Goderich had judged the lobbying for and against Pictou Academy correctly, and in July 1831 had instructed Maitland that a bill should be passed giving Pictou Academy some permanent support. That was easier said than done. Maitland found it impossible to reconcile McCulloch with his Kirk enemies. Pictou town was in a state of war between those hard Presbyterian rivalries; the 1830 election had produced riots that shocked and pained Joseph Howe, and convinced him that the real villains were the Kirk men, no matter whether they had a reverend in front of their name or not.[41]

The 1832 act “to Regulate and Support Pictou Academy” was a compromise, initiated by a Council weary of the war in Pictou. The academy was given £400 per annum for ten years, £250 of which was to go to McCulloch as annual salary. It was given on condition that five of the original Seceder trustees resign and allow the lieutenant-governor to nominate others. Several of the best did resign, and Maitland appointed Kirk men in their place. The purpose was to broaden Pictou Academy’s base of support; but the effect was to transfer the war to inside the Board of Trustees. Maitland hoped that it might work itself out. But disputes so deep rarely work themselves out; if anything, they are apt to grow worse. Feuds continued, the academy suffered, students fell off; McCulloch was disheartened. Had all his years of work, of self-sacrifice, come to this? But he was tough and philosophical:

To maintain it [Pictou Academy] in existence I drowned myself in debt and for years kept my family labouring for nothing and nobody said, Thank you. After a grievous struggle I have neither debt nor wealth but the world is before me and though at my time of life folks get a little stiff about the joints mine I must put to the test… Pictou has very little appearance of being much longer a place for me … To begin the world again my whole stock is health and determination…[42]

The fate of Dalhousie College was also uncertain. The Assembly had by 1835 become impatient. The three years’ postponement of Dalhousie’s £5,000 debt had, with two years’ more of grace, lengthened to five years. William O’Brien moved on 4 February 1835 that the House exact payment, that the attorney general take the necessary steps. John Johnston went further and demanded that the endowment in London be made over, and that some useful building, a poorhouse or a lunatic asylum, be established in Halifax with the money. The Johnston amendment was defeated overwhelmingly, but O’Brien’s carried, twenty to sixteen. The Dalhousie Board of Governors called a meeting on 20 April, and addressed the two surviving trustees of the Endowment Fund – Lord Dalhousie and Chief Justice Blowers – asking them to transfer the funds to Halifax to meet the £5,000 now required by the province, to pay some expenses owing to the estate of Michael Wallace for building, and to pay for some repairs “now absolutely required.”[43]

It sounded desperate and decisive, but it wasn’t. Both Sir Colin Campbell and Lord Glenelg feared that paying the £5,000 back would require either the sale of the college or alienating most of the endowment; if either went, union of the colleges – still a hope – would become impossible. So they devised a means of once more putting off the evil day of reckoning. In the Speech from the Throne opening the 1836 session, the lieutenant-governor appealed to the House to relinquish its claim of 1835, so that there might be sufficient funds “for establishing and maintaining an United College upon liberal principles.” The House was willing to listen. It asked for and got extensive accounts and correspondence of both colleges, which were laid before the House on 7 March.

Dealing with them created considerable discussion. Alexander Stewart moved that while the House approved of having only one college, the governors of King’s had stoutly refused to give up their charter, and that as the session was already advanced, further decision should be put off. For the time being the £5,000 claim would be suspended. Stewart’s comprehensive resolution created a divisive debate. A sweeping amendment was proposed by a leading Methodist, Hugh Bell, newly elected for Halifax: that since every Nova Scotian had an equal claim to education, the House could not acknowledge “the rights of any particular Church or Denomination whatever to preference or predominance of any kind,” and that the House was grateful for the recognition of that basic egalitarian principle by Lord Glenelg and his predecessors. Such even-handed non-denominationalism was more than the House was prepared to stand for, and Bell’s amendment was decisively defeated by thirty-one votes to five. In the end, when the House voted on Stewart’s main motion, the result was a tie, which the Speaker broke by voting in favour of it. Sir Colin Campbell was not pleased. Closing the 1836 session he urged the Assembly to take action next year, for there was not, he said, “means within the Province for maintaining two Colleges.”[44]

But the Assembly did not take action in 1837, and when action did come, in 1838, it took a quite different form. In truth, the project for uniting King’s and Dalhousie, accepted by Lord Dalhousie, urged by Lieutenant-Governor Kempt and his successors, insisted upon by every colonial secretary after Lord Bathurst, had finally come to an end. It was defeated by the indomitable will and indefatigable energy of the Anglicans in Windsor and Halifax, defending an increasingly anachronistic status quo. King’s and its supporters were not malicious; it is proper to say they were interpreting their rights and their duties as they saw them.[45] But there was a world of fighting in those narrow perceptions of rights and duties. King’s was the first college in Nova Scotia; it was also the first to repel, successfully as it turned out, the dangerous idea of One College. In its 1823-4 form, which Lord Dalhousie himself accepted, union may well have been unworkable. At the least, the result might have been two colleges on one campus, perhaps shaking down eventually into one institution, or perhaps ending like King’s College in the University of London after 1828. That would have been better than what did happen. In any case, the Archbishop of Canterbury killed the 1823-4 proposal, and by the 1830s neither colonial secretaries in London nor the Legislative Assembly in Halifax were willing to accept union on King’s terms. By 1838 the Assembly had acquired a new sense of itself and its purposes, and was imbued with a growing and restless distrust of the Council’s stifling, octopuslike grip on the province’s institutions. King’s had been part of that. The new movement to energize Dalhousie College was part of a broader political struggle that came to be called responsible government. Those initiatives came from reform-minded men of the Assembly.

- See Peter Burroughs, “Sir James Kempt,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vii: 458-65. ↵

- Letter from Dalhousie to Kempt, 16 Oct. 1820, confidential, from Quebec, Lord Dalhousie Papers, Microfilm A527, Library and Archives Canada. ↵

- Letter from Wallace to Kempt, 6 Nov. 1820; Letter from Kempt to Dalhousie, 6 Nov. 1820, Lord Dalhousie Papers, Microfilm A527, Library and Archives Canada. ↵

- Letter from Kempt to Dalhousie, 15 Jan. 1821, confidential, from Halifax, Lord Dalhousie Papers, Microfilm A527, Library and Archives Canada. ↵

- Letter from Dalhousie to Blowers, 26 Feb. 1821, Lord Dalhousie Papers, Microfilm A527, vol. 7, Library and Archives Canada ↵

- Letter from Kempt to Dalhousie, 30 Jan. 1821, Lord Dalhousie Papers, Microfilm A527, Library and Archives Canada; Acadian Recorder, 27 Jan. 1821. ↵

- Letter from Dalhousie to Kempt, 10 June 1820, confidential, from on board HMS Newcastle, Lord Dalhousie Papers, A527, Library and Archives Canada; also Whitelaw, ed., Dalhousie Journals, 14 Apr. 1820, p. 191; Letter from Kempt to Dalhousie, 10 Feb., 6 Mar. 1821, Lord Dalhousie Papers, A527, Library and Archives Canada; Nova Scotia Assembly, Journals 1821, 21-23 Feb., pp. 91-103; Letter from Kempt to Dalhousie, 4 June 1821, Lord Dalhousie Papers, A527, Library and Archives Canada. ↵

- Letter from Dalhousie to Kempt, 29 Oct. 1821, Lord Dalhousie Papers, Microfilm A527, Library and Archives Canada; A Mr. Temple had written Lord Dalhousie to say, “I am sorry to find greater difficulty in providing a president for Halifax College than I first anticipated - the great hindrance to our success Mr. Monk tells me is this, clever men can always make so much more at home than this situation holds out.” ↵

- Letter from Kempt to Dalhousie, 21 Jan. 1823, private and confidential, Lord Dalhousie Papers, vol. 11, Library and Archives Canada. ↵

- Letter from Dalhousie to Kempt, 12 Mar. 1823, from Quebec, Lord Dalhousie Papers, vol. 11, Library and Archives Canada. ↵

- Nova Scotia Assembly, Journals 1823, 25 Mar., p. 275. ↵

- Letter from Kempt to Dalhousie, 26 Mar. 1823, Lord Dalhousie Papers, vol. 11, Library and Archives Canada. ↵

- Nova Scotia Assembly, Journals 1823, 25 Mar.- 4 Apr., pp. 275-94. ↵

- Letter from Kempt to Dalhousie, 21 Jan. 1824, Lord Dalhousie Papers, vol. 14, Library and Archives Canada. The letter from McCulloch that Kempt quotes is written to Inglis, from Pictou, 26 May 1823. ↵

- Letter from John Inglis to Kempt, 12 Sept. 1823, Lord Dalhousie Papers, vol. 12, Library and Archives Canada; Nova Scotia Assembly, Journals 1836, Appendix 58, sec. 2, on King’s. ↵

- Letter from Dalhousie to Kempt, 26 Oct. 1823, from Trois-Rivières, Lord Dalhousie Papers, vol. 12, Library and Archives Canada; Letter from Dalhousie to Kempt, 13 Mar. 1824, Lord Dalhousie Papers, vol. 14, Library and Archives Canada. ↵

- Nova Scotia Assembly, Journals 1836, Appendix 58, sec. 2. Blowers had a list of fourteen objections to the union. This quotation is from no. 5. See also G.G. Patterson, The History of Dalhousie College and University (Halifax 1887), p. 19. ↵

- Letter from Dalhousie to Kempt, 13 Mar. 1824, Lord Dalhousie Papers, vol. 14, Library and Archives Canada. Dalhousie was also commenting on objections from Vice-President Cochran of King’s. ↵

- Letter from Michael Wallace to Dalhousie, 10 May 1824, Lord Dalhousie Papers, vol. 14, Library and Archives Canada. See Carol Anne Janzen, “Sir Alexander Croke,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vii: 216-19. ↵

- Dalhousie Board of Governors, Minutes, 13 Jan. 1823, UA-1, Box 14, Folder 2, Dalhousie University Archives; Nova Scotia Assembly, Journals 1836, Appendix 58, p. 135. The Halifax figures are in Halifax currency, where £1 equalled $4. ↵

- An estimate like this makes huge assumptions of what £1 Halifax currency would buy in the 1820s and what its equivalent would purchase in 1990s. Convert to dollars by multiplying by four; then comes a huge leap of faith, viz. multiply by forty. The net effect is to give a very good salary of the 1820s, say £400 per annum, a modern equivalent of $64,000. It is a question of whether such a calculation is worth doing at all; on balance I think some rough contemporary equivalent is more useful than not. ↵

- Letter from Kempt to Dalhousie, 6 July 1825, from London, Lord Dalhousie Papers, Microfilm A527, Library and Archives Canada; for Michael Wallace, see D.A. Sutherland’s article in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vi: 800. ↵

- McCulloch to Lord Dalhousie, n.d., probably 25 Sept. 1823, Thomas McCulloch Papers, 151, MGI, vol. 553, Nova Scotia Archives; Letter from Lord Dalhousie to McCulloch, 4 Nov. 1823, from Quebec, Dalhousie Board of Governors Correspondence, UA-1, Box 28, Folder 15, Dalhousie University Archives. This letter has a hole through it, and some words are missing, but it is clearly in reply to McCulloch’s letter above. ↵

- D.C. Harvey, An Introduction to the History of Dalhousie University (Halifax 1938), p. 32; Patterson, The History of Dalhousie College and University, p. 17. ↵

- D.C. Harvey, An Introduction to the History of Dalhousie University (Halifax 1938), p. 9. ↵

- See Nova Scotia Assembly, Journals 1832, Appendix 41, p. 54, statement signed by Michael Wallace and his son Charles W. Wallace. ↵

- J. Murray Beck, The Government of Nova Scotia (Toronto 1957), p. 21, and Appendix C, p. 349. ↵

- See Phyllis Blakeley, “Sir Brenton Halliburton,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, viii: 354. ↵

- Howe’s speech at the “One College” meeting at Mason’s Hall, 25 Sept. 1843, reported in Novascotian (Halifax), 9 Oct. 1843. ↵

- Nova Scotia Assembly, Journals 1829, 7 Apr., pp. 537-8. ↵

- Board of Governors Minutes, 26 May, 4 Oct. 1829, UA-1, Box 14, Folder 2, Dalhousie University Archives. ↵

- Nova Scotia Assembly, Journals 1830, 27 Feb.-2 Mar., pp. 610-20. ↵

- Board of Governors Minutes, 26 May 1829, 6 Mar. 1829, 6 Dec. 1831, UA-1, Box 14, Folder 2, Dalhousie University Archives; Harvey, An Introduction to the History of Dalhousie University, p. 37, citing correspondence of Jotham Blanchard of Pictou, from Glasgow, 12 Oct. 1831. See also Patterson, The History of Dalhousie College and University, p. 21, quoting the Pictou Observer, 23 Nov. 1831. ↵

- Sir George Murray to Sir Peregrine Maitland, 31 Aug. 1829, in Nova Scotia Assembly, Journals 1836, Appendix 58, p. 104. ↵

- Goderich’s despatch is described in detail in Patterson, The History of Dalhousie College and University, p. 22; Board of Governors Minutes, 13 July 1832, UA-1, Box 14, Folder 2, Dalhousie University Archives. Archibald’s protest is dated 6 Jan. 1832. He was also warning the joint meeting not even to bother drafting a bill for the union, “as the Assembly would be more influenced by the general wishes of the country than by any opinion intimated by the Governors.” ↵

- Letter from Maitland to Goderich, 19 Mar. 1832, Colonial Office despatches on microfilm, at Library and Archives Canada and Nova Scotia Archives, See CO 217/154. . Maitland’s opinion on the general attitudes in British North America is worth noting; he had been lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada from 1818 to 1828 prior to coming to Nova Scotia. ↵

- Glenelg to Campbell, 30 Apr. 1835, in Nova Scotia Assembly, Journals, 1836, Appendix 58, pp. 105-7. ↵

- Nova Scotia Assembly, Journals 1836, Appendix, p. 121; Patterson, The History of Dalhousie College and University, p. 24. ↵

- Acadian Recorder, 30 Aug. 1834 to 27 Sept. 1834. ↵

- 3 Feb. 1836, quoted in J. Murray Beck, Joseph Howe: Conservative Reformer 1804-1848 (Kingston and Montreal 1982), p. 152. ↵

- 3 Feb. 1836, quoted in J. Murray Beck, Joseph Howe: Conservative Reformer 1804-1848 (Kingston and Montreal 1982), p. 152. ↵

- The Pictou Academy Act is 2 Wm. IV, cap. 5, given royal assent 30 Mar. 1832; Thomas McCulloch gives useful details; see Letter from McCulloch to James Mitchell of Glasgow, 6 Nov. 1834, from Pictou, Thomas McCulloch Papers, vol 553, no. 62, Nova Scotia Archives. ↵

- Nova Scotia Assembly, Journals 1836, 4 Feb., p. 833. The story is a little more complicated than the text suggests. The first part of O’Brien’s resolution, that the House require repayment of the £5,000, was passed, twenty-two to sixteen. The second part of it, that the attorney general take immediate steps to get the money, passed twenty to sixteen. ↵

- Nova Scotia Assembly, Journals 1836, 21 Jan., p. 883; 7 Mar., pp. 1004-5; 23 Mar., pp. 1049-50; 4 Apr., p. 1090. ↵

- Two useful works on this complex period of Nova Scotian politics and education are W.B. Hamilton, “Education, Politics, and Reform in Nova Scotia, 1800-1848” (PH.D. thesis, University of Western Ontario 1970), and Susan Buggey, “Churchmen and Dissenters: Religious Toleration in Nova Scotia, 1758-1835” (MA thesis, Dalhousie University, 1981). ↵